I'm a strength coach. I spend much of my day making people bigger, faster, and stronger – with a heavy emphasis on the latter.

I love the effect something as simple as getting stronger has on the human body. Performance improves while imbalances fade, and with time a slow, brittle physique is replaced by something stronger, faster, more athletic, and seemingly forged from titanium alloy.

Not to mention, more muscular – which is why a small piece of my soul dies every time I hear something like, "Getting strong isn't really important to me, I'd rather just look strong."

I understand the aesthetic bias we have as a society, and that having a six-pack is higher on many trainee's priority list than how much weight they can deadlift.

But one of the things I take pride in as a coach is my ability to keep things simple, so for all you lifters with iPhones filled with shirtless bathroom pictures, let me state this as simply as I can:

It's imperative to build a solid base of strength in order to build mass. And if you train for strength – and don't eat like a moron – the aesthetics you crave will undoubtedly follow.

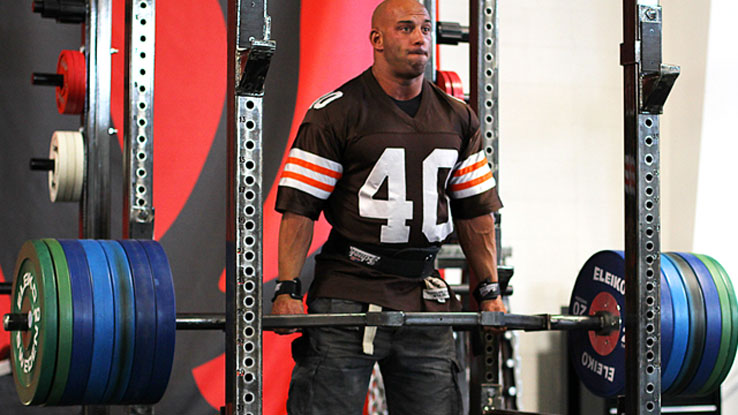

I doubt you've seen many guys who bench 405 or squat 500 that are small. On the other hand, walk into just about any commercial gym and you'll see loads of 150-pound dudes running the rack on curls and performing drop sets of triceps pushdowns.

What good is a six-pack and veiny 14-inch arms if you can't deadlift your way out of a wet paper bag and your waif-like body resembles something that would get crushed against the wall by a surging crowd of angst-filled teenaged girls at an Avril Lavigne mall appearance?

If you're a newbie (or even someone who's been training for a few years and just not happy with the end results), this article will serve as a reminder to focus on the basics, get strong, and steal a page from Ms. Lavigne and stop making things so complicated!

The Strength Base

As stated, you can't have fitness qualities like agility, power, endurance, and strength endurance – let alone an impressive physique –- without having a solid base of strength.

It is possible to develop a very impressive physique with just moderate strength levels, but your quest for huge arms and a set of pecs that can support a pitcher of Dos Equis will be a losing venture if a spandex-clad Richard Simmons can beat you in an arm wrestling match.

Using an analogy I shamelessly stole from strength coach Mike Boyle, it's like giving your Ford Focus a sweet paint job, spoilers, racing tires, and a roll cage in the belief that it will win the Daytona 500.

Unless you do something about increasing the horsepower of the car – you can add all the bells and whistles you want and even dress like Danica Patrick – it ain't gonna happen.

The same can be said for those that are more aesthetically minded. An emphasis on strength must be a part of the program design, yet it's one that many trainees dismiss – and as a result, they never attain the physique that they aspire to have.

What Would Pareto Do?

The Pareto Principle was inspired by the Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto, who back in the early 1900s demonstrated that 80% of the wealth in Italy was owned by only 20% of the population.

Interestingly, the rule has since been studied and applied to every facet of life, revealing that certain activities tend to give more return on investment than others. Put another way – 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes.

The fitness industry is no different. We all know that guy who spends 45 minutes doing every variation of biceps curls imaginable yet looks like he spends more time lifting hair gel than weights.

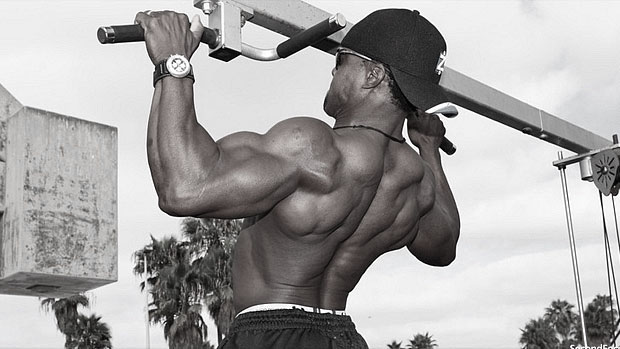

I'm not suggesting that curls are a complete waste of time, and yes, I do them myself (on occasion). But if you're a newbie weighing all of 150 pounds soaking wet – or even if you have a few years' experience yet can't perform ten honest bodyweight chin-ups (sternum touches the bar on every rep) – your time can be better spent elsewhere.

A high premium is placed on the big compound movements like deadlifts, squats, bench presses, chins, rows, etc.

These are the movements that are going to get you strong and add serious mass to your frame. There's no science behind that statement, it's just common sense.

I have the luxury of being the co-owner of one of the premier strength and conditioning facilities in the country, Cressey Performance. While we take great pride in the meticulous nature of our approach to assessing and writing kick-ass programs for our athletes, people are often surprised by the simplicity behind the madness.

Fact is, if you look at the bulk of our programs, many are fairly "minimalist."

Sure, we may have to get more elaborate when working with a client with a unique injury history, but for the most part, we program 3-4 movements, max.

The first movement of the day is the "money" movement. Whether it's a deadlift, a squat variation, or even an overhead press, it's the exercise that's going to get the most attention, and most likely make the person want to hate life.

There's no such thing as a "chest and back day." If I program deadlifts, it's a "deadlift day." And, assuming no special circumstances – injury, limited training frequency – everything programmed after that is to complement the main movement and/or fix any imbalance or weakness that needs to be addressed.

De-Clutter your Training

In his phenomenal book, The Power of Less: The Fine Art of Limiting Yourself to the Essential...In Business and Life, Leo Babauta discusses how one can go about "de-cluttering" their life to make him or herself more efficient.

In short, he teaches people how to get shit done, whether it's stepping away from their email or making an effort to get up earlier in the day to get a head start on things.

We can take the same approach when it comes to training. If more trainees performed less on any given training session and just made a concerted effort to go balls to the wall on the movements that mattered, they'd see marked improvements in their strength and physique.

The programs we write have very little "fluff" involved and every exercise serves a purpose. Without giving away too many trade secrets:

- We coach the hell out of our athletes and clients. Walk into our facility on any given day and I'll tell you what you'll never find: someone deadlifting with a rounded back, someone cutting their squats high, someone benching with their feet in the air, etc.

- Rarely will you see us use straight sets. People waste enough time in the gym as it is. I've witnessed on numerous occasions, when training at commercial gyms, someone perform a set and then spend the next ten minutes texting on their phone or playing a round of Angry Birds.

- To that end, every session begins with basic, tried and true compound movements. As noted, the first movement is the main focus for that particular training session, and I prefer to pair these with some low-grade activation or mobility drills (fillers), rather than another strength exercise, so as not to alter or take away from the desired training effect.

Here's an example:

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Conventional Deadlift | 4 | 3 |

| A2 | Split-Stance Adductor Mobilization and Wall Hip Flexor Mobilization (both to be performed after each set of deadlifts) | 4 | 8/leg |

This way I can address any postural deficits or weaknesses that may exist with the filler exercises while better controlling accumulated fatigue and keeping the trainee as fresh as possible for every set of deadlifts.

All accessory work, for the most part, will serve just to "accessorize" or complement the main movement for that day (along with bringing up weaknesses). Another thing to consider when determining accessory work is where a trainee may "fail" in any given lift.

For example, if someone is really slow off the ground when deadlifting, I may structure a session like this:

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Conventional Deadlift from Deficit (standing on plates) | 4 | 3 |

| A2 | Split-Stance Adductor Mobilization and Wall Hip Flexor Mobilization (both to be performed after each set of deadlifts) | 4 | 8/leg |

| B1 | 1 1/2 Front Squat | 3 | 6 |

| Squat down as deep as you can, come up half way, go back down as low as you can, then come back up to the starting position. That's one rep. | |||

| B2 | Pallof Press | 3 | 8/side |

| C1 | Dumbbell Reverse Lunge | 3 | 10/leg |

| Many fail to realize that the quadriceps come into play significantly on the initial pull of a deadlift. That said, some dedicated work to hammer the quads wouldn't be a bad idea. | |||

| C2 | X-Band Walk | 3 | 8/leg |

| D | Eat copious amounts of dead animal flesh | ||

Using the bench press as an example, let's assume that someone has a hard time at lockout.

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 3-Board Press | 4 | 5 |

| A2 | Quadruped Extension Rotation | 3 | 8/leg |

| B1 | Close-Grip Barbell Floor Press | 3 | 10 |

| B2 | Chest-Supported Row (pronated grip) | 3 | 8 |

| C1 | One-Arm Half Kneeling Cable Row | 3 | 8/arm |

| C2 | One-Arm Strict Dumbbell Military Press | 3 | 6/arm |

| D | Seriously, go eat something |

Now let's use an example where someone sucks at squatting. In this case, they have a hard time getting to depth without their butt tucking.

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Box Squat (to a height where their spine doesn't tuck) | 3 | 5 |

| Ass to grass squatting is cool, but not everyone can (or should) squat that deep if it's going to break their spine in half. I'd much rather someone squat to a depth that's safe, yet still grooves a nice squat pattern. As they grow more proficient, we can lower the squat depth. See video below. | |||

| A2 | Wall Ankle Mobilization | 3 | 8/leg |

| And, because lack of ankle dorsiflexion plays into limited squat depth, we might as well make ample use of our rest time. | |||

| B1 | Dumbell Bulgarian Split Squat | 3 | 8/leg |

| B2 | Pallof Press | 3 | 10/side |

| C1 | Glute Ham Raise or Barbell Supine Bridge | 3 | 8-10 |

| C2 | Chin-Up | 3 | 5 |

As you can see, we're only talking about 3-5 movements per session, which is a far cry from the standard 6-8 most trainees feel they need to squeeze in.

When you think about it, many have a bad habit of adding in more exercises, at the expense of mastering none – and that's a huge monkey wrench when it comes to making progress and building a physique you can be proud of.

The key, then, is to perform the basic movements well, and to focus on the things that will strengthen your weaknesses.

Progressive Overload – Use It!

All progressive overload means is continually increasing the demands on the body to make consistent gains in muscular strength, size, and sometimes endurance.

Put another way, to get stronger and subsequently bigger, you must subject the body to a progressive stimulus to force it to adapt. It's surprising to me how many people fail to recognize this.

There are a million and one different variables to consider in terms of progressive overload – more reps, more sets, increased training frequency, increased intensity (as a % of 1RM), manipulating rest time, etc. – but I'm going to share only one option, which takes an admittedly Captain Obvious approach.

Two Rep Window

When I prescribe a certain rep scheme – say, five repetitions – what I really mean is 3-5 repetitions, sort of like a rep window.

This way, if someone is performing an exercise and their technique starts to falter, I'd rather see them stop the set short (within the allotted window) than run the risk of injury.

So, for example, if I have someone performing a bench press for three sets of five, it may look something like this:

- Set 1: 200 x 5 (reps looked good and they were all pretty fast. Chest bump!)

- Set 2: 200 x 4 (technique started to fail, bar speed too slow, no point in grinding out a fifth rep and run the risk of missing it.)

- Set 3: 200 x 3 (still within the two rep window)

The objective for the following week(s), then, would be to try to hit those "missed" repetitions until all are successfully completed. When they are, increase the weight and repeat the process.

Now, if they were able to easily perform every repetition the first time through, then they know the weight was too low and they can go ahead and increase it.

Conversely, if at any point they drop out of the "two-rep window" (in this case, anything under three reps), the weight is too challenging and they should lower it.

Either way, using this approach ensures that there's a concerted effort to increase the weight on a consistent basis, and that's the name of the game.

As I mentioned, there are numerous ways to implement progressive overload, but you don't necessarily have to approach it like long division and make it more complicated than it has to be – especially the less advanced you are.

Conclusion

Many of you probably think that the solution to your lack of gains lies in some secret exercise, training split, or set-and-rep scheme, and that you can't fathom not hitting (insert your favorite muscle group) from every angle imaginable.

Trust me on this: you'd see better results if you stopped focusing on the fluff and started focusing on getting stronger at the big basics.

And if you're not getting stronger, if you're like most people, it's because your routine sucks and you're spinning your wheels performing every movement in Arnold's Encyclopedia of Modern Bodybuilding.

If this is the case, it's time to go back to the basics and give your body a chance to grow stronger.