Cyanadin 3-Glucoside and Body Composition

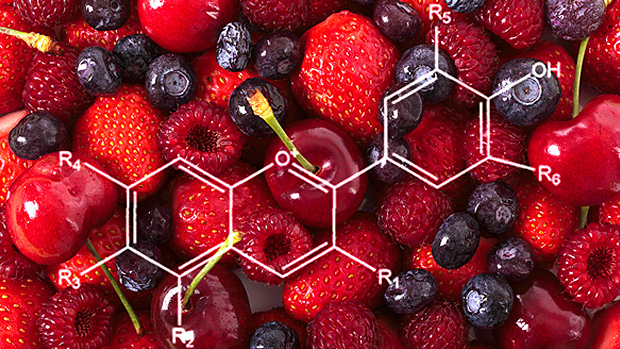

Anthocyanins are the plant flavonoids responsible for the red, purple, and blue hues evident in many fruits, vegetables, cereal grains, and flowers. They appear to have multiple benefits to the human body.

One anthocyanin in particular, C3G (cyanadin 3-glucoside), when taken in sufficient amounts in supplement form, actually improves body composition. Lifters and athletes who take it before training and before the biggest meal of the day end up adding muscle and losing fat.

This muscle gain/fat loss was always thought to be the direct cause of C3G's positive effects on insulin sensitivity. After taking it, muscle cells become more responsive to the effects of insulin and nutrients are preferentially directed towards muscle, thus setting up muscle cells to grow.

Additionally, C3G has long been known to increase lypolysis (fat burning) by increasing the production of adopokines (cell-signaling proteins) like adiponectin, which regulates glucose levels and breaks down fatty acids.

However, we recently became aware of new research that this C3G-mediated rise in adiponectin may also be contributing to muscle growth.

No Adiponectin, No Muscle Growth

It was originally thought that the expression of adiponectin was limited to adipocytes, or fat cells, but it's been repeatedly shown in the last ten years or so that adiopnectin is also produced by skeletal muscle fibers and may, in fact, influence the genetic make-up of muscles.

However, adiponectin may play an even bigger role in muscle physiology. It seems that exercise-induced hypertrophy may be impossible without the presence of adiponectin.

Monster Mice

Scientists at the 2016 Experimental Biology Meeting described an experiment where they compared mice that were genetically designed to have no adiponectin (their gene for adiponectin had been "knocked out") against wild mice with their adioponectin gene intact.

Both groups of mice were split into two sub-groups, one that ran on an incline treadmill for an hour every day for 8 weeks, and one that was sedentary.

After 8 weeks, the scientists measured their soleus and gastrocnemius muscles to see if they'd grown. Neither the adiponectin-free exercise group nor the adiponectin-free sedentary mice experienced any significant muscle growth. Nor did they add any significant body mass.

However, the wild mice, with their adioponectin gene intact, experienced fairly dramatic weight gain and muscle growth:

- The exercise group increased body mass by 13.9% (compared to 11.7% in the sedentary group).

- The mass of the soleus muscle of the exercise group increased by 20.2 milligrams (compared to 12.2 milligrams in the sedentary group).

- The mass of the gastrocnemius of the exercise group increased by 248.8 milligrams (compared to 178.5 milligrams in the sedentary group).

More Adiponectin, More Muscle?

The researchers concluded: "These results indicate that exercise-induced hypertrophy of skeletal muscle and associated improvement of vascular function does not occur in mice deficient in adiponectin. These results suggest that adiponectin is vital to the vascular and metabolic adaptations that occur in muscle in response to aerobic exercise training."

Granted, this is only one study, and a study done with mice to boot, but if scientists can confirm their findings, and these finding extend to humans, it adds a new chapter to our understanding of muscle growth and possibly furthers our understanding of the effects of C3G and other adipokine-modulating compounds.

Reference

- Gorman, Katherina, et al, "Adiponectin is necessary for exercise training-induced muscular hypertrophy and vascular adaptation." The FASEB Journal, April 2016. Vol. 30 no. 1 Supplement 1240.23.