"Oh come on, live a little!"

"Don't you ever eat anything that's bad for you?"

"I could never do what you guys do, I like food waaaayyyy to much for that!"

Those quotes sound familiar, don't they? I know I've heard them hundreds of times. But don't take my word for it. Studies have shown that every 60 seconds, someone, somewhere in the world, is uttering some permutation of one of these phrases. (1) The most annoying part is that the perpetrators don't seem to "get it."

Now, my normal response is to smile and chuckle it off while deliberately and noticeably glancing down at the extra pounds of "life" around their midsection. But what I really feel like doing is snapping back with something like, "Oh, so what you're telling me is that stale, chocolate brownies are the secret to what you call 'living.' That's interesting. You know, in all honesty, my brethren and I do eat stuff that's 'bad' for us from time to time; we just eat it less frequently than you do, chubby. And this, my opponent of self discipline, is what makes our enjoyment of food waaaayyyy superior to yours!"

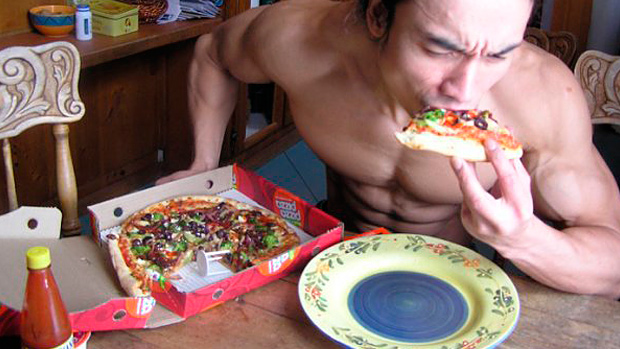

After all, bodybuilders love a good cheat meal! So much so that if our livin' and food-lovin friends had occasion to watch us take down an all-you-can-eat buffet or a Christmas goose, their mouths would fall open, spilling cranberry sauce all over the "good linen." But herein lies the problem. While needing to eat big from time to time (for both physiological and psychological reasons), we are a rather vain species, always wondering, "Who's the fairest of them all?" Last time I looked into my mirror after a cheat meal and asked that question, my mirror replied, "Uh, JB, in case you didn't know this, a 10,000-calorie meal doesn't exactly sculpt the abs."

So with the holidays coming up it's about time someone talked about "damage control." After all, in the Berardi house, "cheat days" and holidays carry with them important pre and post meal rituals. Therefore, in this article I'll share a few tricks with you – taken straight from the research journals – for minimizing the damage caused by eating your weight in turkey and candied yams.

As Tiny Tim would say, "God bless us, every one!"

I don't know how many times I've heard the following question but it never ceases to make me chuckle.

"So John, I believe in a weekly cheat meal. Do you?"

My sarcastic response is usually something like, "You know, before today I wasn't sure if the cheat meal existed but the empirical evidence located around your waistline has made me a believer."

Then I usually answer the question properly. I think that a modest weekly cheat meal is just fine for some people while it's a mistake for others. Here are some circumstances in which they're appropriate and some in which they're not:

- Cheat meals should only be planned during periods of the year when you're trying to gain mass. During this time, cheat meals eaten once per week or once every two weeks are fine, depending on your goals or your body-fat percentage. The leaner you are, the more often you can cheat. But don't force it. Calling the binge session a "cheat meal" and using it as an excuse to eat a bunch of junk food is not the way to get big and muscular.

- From what I've seen, the following always holds true. If you're honestly overeating large amounts of good foods on a regular basis, you'll certainly be getting all the good calories you need to grow. And you won't be hungry for crappy food. In fact, one way I assess whether my clients are eating enough good bodybuilding food each week is whether they are craving cheat foods. If so, they need more calories through the week. Scientifically, this makes sense since chronic overfeeding causes the brain to realease satiety hormones and these hormones signals tell the brain's hunger centers to "shut up and sit down."

- Cheat meal frequency and/or size should be minimized when over 15-20% body fat. I've discussed this before in a previous Appetite For Construction column. Basically, the fatter you are, the more likely that any excess food will be shuttled toward body-fat storage rather than muscle mass. So, if you're fat, minimize your over eating.

- Don't have cheat days or meals while you're trying to lose weight. I know, I know, you've always heard talk about "stoking the metabolic fire" or some nonsense like that, but simply put, that's bunk. First, psychologically, it's very difficult to stay disciplined after a cheat meal. After weeks of dieting, the taste buds, which have all but given up hope, are stirred back to life. Each time you cheat on the diet, it's more difficult to stay strict when next you're being tested by the devil on your shoulder. "Come on, John, you know you want a slice of pizza. Remember, you didn't get fat after your cheat meal on Sunday. This one time will be fine, too."

- And physiologically, there's no sound reason to have a cheat meal. One meal will not upregulate your sluggish dieter's metabolism, despite what you've heard. Sure, the metabolic rate gets upregulated for a few short hours after the big meal, but no way will this thermogenesis account for the large caloric load you'll be dumping into the gut at once.

So my final answer is that it's okay for some people to "believe in" the cheat meal. Others however, should categorize the cheat meal right up there with the Loch Ness Monster and Big Foot.

Before we actually start to talk about what we can do to minimize the damage caused by eating big, I want to tell you about some of the physiological events that occur when you sit down to an all-you-can-eat feasting extravaganza. When overfeeding for a single meal, the following happens:

- Increased blood insulin levels. This decreases fat mobilization and oxidation.

- Increased storage of fat and carbohydrate. It's been estimated that in the average person, outside of the post exercise window, a meal consisting of over 750 calories (regardless of the macronutrient content) leads to measurable fat storage.

- Increased sympathetic autonomic nervous system activity (norepinephrine release, epinephrine release, and related autonomic nervous activity). (2)

- Increased release of thyroid hormone (T3 and T4). (3)

- Increased thermic effect of feeding. This is the cost of metabolizing the food. (3)

- Increased percentage of energy comes from carbohydrate oxidation while a decreased percentage of energy comes from fat oxidation. (4)

- Increased spontaneous activity or NEAT (non-exercise activity thermogenesis). This represents the activities of daily living, changes of posture, and fidgeting. (5,6,7)

While these changes are usually seen in most subjects, individual responses are quite variable. In fact, as you might expect, your genetic make-up and exercise activity have a lot to do with your response. Here's a list of some of the ways that different people respond differently to overfeeding:

- Lean people have a significant increase in sympathetic autonomic nervous system activity while obese people often have no response. (2)

- Lean and obese people show increases in T3 and T4 release but there's large variability. This variability may be explained by the fact that the obese may release less thyroid hormone when overfeeding. (3)

- When exercise-trained people overeat, they may store more carbohydrate while burning more fat. Non-exercisers, on the other hand, may store more fat and burn more carbohydrate. (4)

- Weight-gain resistant people tend to experience huge increases in NEAT as a result of overfeeding (most of the extra calories are burned, not stored), while people who gain weight easily tend to store most of the extra calories as fat. (5,6,7) Most interestingly, in one overfeeding study, subjects were given 1000 calories above maintenance per day. The weight-gain resistant subjects in this study oxidized a whopping 70% of those 1000 calories. Those who gain weight easily actually stored most of those calories as fat. After 8 weeks of overfeeding, fat gain varied almost 10-fold among subjects, ranging from a gain of only 0.79 lb to a gain of 9.31 lb!

- In lean people, the normal insulin response to a meal only minimally affects fat mobilization and fat storage. However, in fatter people, the normal insulin response to a meal nearly shuts down fat mobilization and leads to large increases in fat storage.

I hope it's clear that although there are some common ways that the body responds to overeating, these responses are highly variable and this variability determines how damaging the binge will be. So, knowing the way you respond to the binge is critical to how you should manage the binge. As I said earlier, if your physiology demands it, some of you may have to forgo "cheating" altogether.

Regardless of how we respond to overfeeding, we all know that the occasional binge is inevitable. So now let's talk about what we can do to minimize the damage. The first area I would like to cover is exercise. Then, I'll talk about nutrition on the day of the binge, and lastly, I'll talk about supplement strategies.

One key component of your damage control strategy is exercise. There are two schools of thought regarding exercising on "cheat day," one group arguing that exercising before the meal is better while one argues that exercising after the meal is better. Let's look at the data.

In one study, lean and obese people performed low intensity and high-intensity exercise with and without a meal afterward. (9) Let's talk about the effects of the exercise alone for a minute. While both groups of exercisers burned the same amount of calories during the exercise, the post-exercise energy expenditure was 14% in the high-intensity group and 6% in the low-intensity group.

I'm sorry to go off on a tangent here, but for all those who think they have to switch their cardio over from low intensity to high intensity, I want to point out a few things. If the average person's basal metabolic rate is 2000 kcal per day (83 kcal per hour), this means that the high-intensity group burned an extra 6 calories per hour vs. the lower intensity exercise group. Since this type of metabolic increase usually lasts for only 5 hours or so, we're only talking an extra 30 calories per day here! So don't make any silly conclusions about what type of exercise is more effective.

Anyway, back to the study. When a 720-kcal meal was ingested, the combined effects of the exercise (either type) plus the feeding led to larger increases in metabolism than either one could produce alone. But even more importantly, the RQ (respiratory quotient; it's a measure of the mix of fuels burned) remains lower if exercise preceded the meal versus eating a meal alone. This means that exercising before eating prevents some of the large shift toward carbohydrate burning after eating. And this means more fat will be burned for energy if exercise precedes your meal than if you were to eat the meal alone.

In another study looking at pre-meal exercise, subjects performed swimming exercise before eating. (11) In this study, swimming before eating a meal led to an additional 4.6 calories being burned per hour versus the meal alone. As with the study above, the absolute amount of calories burned isn't all that impressive, but in my opinion, the more important issue here is the shift in metabolism to less carbohydrate burning and more fat burning in the hours after the exercise and the meal. So it looks like exercising before eating is the way to go, right?

Not so fast! On the other side of the fence we have a study looking at post-meal exercise. In this one, subjects performed either high or low-intensity exercise after a 750-kcal meal.(10) In this study, the researchers noted a synergistic effect between the meal and the exercise. With the combination of the meal and exercise, more calories were burned over the next three hours than if the meal was eaten without exercise or exercise was done without a meal. Again, there were no differences between groups.

Since the studies seem to show that both eating before and after exercise leads to metabolic rate increases and more fat oxidation, what about studies comparing pre-exercise feedings to post-exercise feedings? Well, I've got them for you, too!

In two publications comparing the effects of pre-exercise meal feedings to post-exercise meal feedings, the authors showed that the 3-hour thermic effect of food was significantly greater when the meal was eaten before exercise than when the meal was eaten after exercise (13,14). The exercise bout in this study happened to be 30 minutes of cycling.

From these data it seems that when we put the two head to head, the binging before exercise may be superior to binging after exercise. As a side note, getting back to the individual differences aspect, the authors showed that lean subjects burned more calories in every condition (meal alone, pre-exercise meal, and post exercise meal) when compared to obese subjects.

So is that it? Is eating before exercising the way to control the damage? It appears so. In another study comparing the effects of pre-exercise meal feedings to post-exercise meal feedings, the authors verified the results from above (12). In this study, a 910-kcal meal followed by a 25-minute treadmill run resulted in greater energy expenditure than when the run came before the meal.

Bottom line, when it's time to pig out, if you have to make a choice between exercising before or exercising after the meal, after the meal is the way to go. But what if you have the day free, plan on eating enough for a small army, and want to really control the damage? Since there are no studies on weight training or pre and post-meal exercise, I'm going to have to theorize here. What I would do is the following:

A few hours before the meal, I would perform a glycogen-depleting workout. This could be a 30-60 minute cardio bout or a 15-30 minute bout of high-intensity interval training. Then, a few hours later, I would eat the big meal. Then, as soon as I can button up my pants again, I would hit another workout. This one could be another cardio bout (if it's an "off" day) or a weight-training bout if it's my lifting day.

I know this section seems out of place since it's the eating we're talking about that actually causes the damage, but what I'm referring to in this section is the fact that the composition of the meals in and around your cheat meal can actually improve your physiological response to the binge.

Studies since the early '80s have demonstrated what's known as a "second meal effect." Basically, if you eat a meal that's low in fat and contains a high percentage of low-glycemic index (GI) carbohydrates, resistant starch (RS), and dietary fiber (DF), your responses to your next meal are improved. Specifically, you'll remain satiated longer between meals and during your next meal, you'll have decreased glucose and insulin responses as well as reduced serum triglyceride (TG) levels. (15,16, 17)

In fact, this is the case whether your next meal has a high GI or a low GI. Although the studies cited here refer to the effects of a low GI/high DF carbohydrate breakfast followed by a high or low GI lunch, your glucose tolerance will also be improved during a high GI breakfast if you eat a low GI/high DF carbohydrate meal the night before.

So, my recommendation would be to consume a low GI/high fiber carbohydrate meal a few hours before your big feast. This will help control the glucose and insulin responses to your gluttonous meal as well as keeping high triglyceride levels at bay. It might also prevent you from eating yourself into a bloated stupor.

Reconciling these recommendations with the ones I made regarding exercise, a few hours before you break bread you should do a glycogen depleting exercise bout and follow it up with a moderate meal of low-GI carbs and high fiber.

In addition to encouraging you to utilize the "second meal effect," I'd like to give you some tips on how to organize the rest of your daily food intake.

- Eat as you normally would (every few hours) before your cheat meal. Don't fast in preparation for your elaborate meal.

- Once you've done the damage, don't eat again that same day until you start to feel hungry or at least wait until you don't feel painfully full any longer. If you're not used to huge calorie loads, you'll undoubtedly remain full for hours and hours afterward. This is due to the super-slow digestion that's taking place as a result of all that food volume and all that saturated fat. Don't force yourself to eat on a schedule on these days because you're afraid of catabolism or something. By feasting you've created a huge nutrition storage depot in your stomach and the nutrition will be slowly released for hours to come.

- On the following day after a ridiculous binge, get right back on your regular diet. Don't try to eat less or try to "diet" the binge off. It doesn't work and just screws you up even more for days to come. You may not feel much like eating the next day. Eat anyway. You may feel bloated. Eat anyway.

So far we've discussed how the body responds to a huge meal and some exercise and nutritional strategies to manage your binge. Now I'd like to present some supplement strategies for helping the body cope with your gluttony.

As discussed earlier, the body responds to large meals with increased sympathetic activation and an increased thyroid hormone response. (2,3) Since this seems to be the body's strategy for dealing with the caloric load, why not mimic this ourselves with supplements? Although most of you know I'm not a fan of chronic use of stimulants or fat-loss supplements/drugs, I'm not opposed to the acute use of them. Therefore, on the day of the feast, taking a few stimulants like Hot-Rox® Extreme and a few doses of a thyroid drug like T2 or T3 might help give the metabolism a much needed kick start.

Studies have shown that beta agonists can stimulate metabolic rate in a similar manner to the way diet increases sympathetic nervous system activity. (21) Specifically, ephedrine can increase the thermic effect of feeding by over 30%. (18)

As far as thyroid hormones, T3 injections in rats can potentiate the effects of diet-induced thermogenesis on metabolic rate and brown adipose tissue activity. (19) Studies also show that T2 acts directly on the mitochondrial respiration while T3 and T4 must first increase oxidative enzyme levels. This means that T2 has a much more rapid stimulation of metabolic rate (1 hour for T2 vs. 24 hours for T3). Some authors have concluded that T2 may be beneficial in situations requiring rapid energy like cold exposure or overfeeding (20). So a thyroid and ephedrine-type cocktail may increase meal induced thermogenesis and offer a nice degree of damage control.

While prescription "fat blockers" like orlistat may help keep some of that saturated fat and cholesterol out of your blood stream, the consequences of such drugs (i.e. poor vitamin absorption and the famous "anal leakage") may be more detrimental than the fat intake itself. (23) While the prescription drugs do prevent fat absorption, human studies on over the counter "fat blockers" like chitosan have shown that these supplements have no impact on weight loss or fat excretion. (23,24)

Since most cheat meals are often loaded with carbohydrates and sodium, water retention is usually a consequence of the binge. Mild, over the counter diuretics like dandelion and uva ursi may help keep the fingers moving through a full range of motion.

Also, look into selective nutrient repartitioning agents like Indigo-3G®. In short, this will help your body use those extra carbs to fuel muscle growth instead of it just being stored as fat.

So now that I've discussed the data supporting my exercise, nutritional, and supplemental strategies, here's a quick review:

Exercise: If you have to choose, work out after eating, but ideally you'd work out a few hours prior to eating as well.

Nutrition: Eat normally before your binge and take advantage of the second meal effect. After your binge, eat again when you're hungry or when you don't feel so full. Get back on your regular diet the next day.

Supplements: Taking stimulants like Hot-Rox® Extreme and thyroid enhancers like T2 or T3 during the day of the big feast may fire up the metabolism. In addition, taking mild diuretics may keep the excess water off.

Hopefully, these damage control strategies will allow paranoid types to eat with the family on major holidays without having to break out their golden engraved tub of cottage cheese. And if you're the type who thinks Sunday just isn't Sunday without a trip to Wong's Buffet Palace, you can continue to do so without carrying out a few extra pounds of pork-fried rice on your love handles.

- Matsumoto T et al. Comparison of thermogenic sympathetic response to food intake between obese and non-obese young women. Obes Res. 2001 Feb;9(2):78-85. PubMed.

- Poehlman ET et al. Genotype dependency of the thermic effect of a meal and associated hormonal changes following short-term overfeeding. Metabolism. 1986 Jan;35(1):30-6. PubMed.

- Bowden VL et al. Effects of training status on the metabolic responses to high carbohydrate and high fat meals. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2000 Mar;10(1):16-27. PubMed.

- Snitker S et al. Spontaneous physical activity in a respiratory chamber is correlated to habitual physical activity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001 Oct;25(10):1481-6. PubMed.

- Vanltallie TB. Resistance to weight gain during overfeeding: a NEAT explanation. Nutr Rev. 2001 Feb;59(2):48-51. PubMed.

- Levine JA et al. Role of nonexercise activity thermogenesis in resistance to fat gain in humans. Science. 1999 Jan 8;283(5399):212-4. PubMed.

- Katzeff HL et al. Decreased thermic effect of a mixed meal during overnutrition in human obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989 Nov;50(5):915-21. PubMed.

- Brodeur C et al. The metabolic consequences of low and moderate intensity exercise with or without feeding in lean and borderline obese males. Int J Obes. 1991 Feb;15(2):95-104.

- Goben KW et al. Exercise intensity and the thermic effect of food. Int J Sport Nutr. 1992 Mar;2(1):87-95. PubMed.

- Nichols J et al. Thermic effect of food at rest and following swim exercise in trained college men and women. Ann Nutr Metab. 1988;32(4):215-9. PubMed.

- Davis JM et al. Weight control and calorie expenditure: thermogenic effects of pre-prandial and post-prandial exercise. Addict Behav. 1989;14(3):347-51.

- Segal KR et al. Thermic effect of food at rest, during exercise, and after exercise in lean and obese men of similar body weight. J Clin Invest. 1985 Sep;76(3):1107-12. PubMed.

- Liljeberg HG et al. Effect of the glycemic index and content of indigestible carbohydrates of cereal-based breakfast meals on glucose tolerance at lunch in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 1999 Apr;69(4):647-55. PubMed.

- Liljeberg H et al. Effects of a low-glycaemic index spaghetti meal on glucose tolerance and lipaemia at a subsequent meal in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000 Jan;54(1):24-8. PubMed.

- Holt SH et al. The effects of high-carbohydrate vs high-fat breakfasts on feelings of fullness and alertness, and subsequent food intake. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 1999 Jan;50(1):13-28. PubMed.

- Horton TJ et al. Aspirin potentiates the effect of ephedrine on the thermogenic response to a meal in obese but not lean women. Int J Obes. 1991 May;15(5):359-66. PubMed.

- Rothwell NJ et al. Influence of thyroid hormone on diet-induced thermogenesis in the rat. Horm Metab Res. 1983 Aug;15(8):394-8. PubMed.

- Lombardi A et al. Effect of 3,5-di-iodo-L-thyronine on the motochondrial energy-transduction apparatus. Biochem J. 1998 Feb;330(1):521-526. PMC.

- Rothwell NJ et al. Sympathetic mechanisms in diet-induced thermogenesis: modification by ciclazindol and anorectic drugs. Br J Pharmacol. 1981 Nov;74(3):539-46. PubMed.

- Guerciolini R et al. Comparative evaluation of fecal fat excretion induced by orlistat and chitosan. Obes Res. 2001 Jun;9(6):364-7. PubMed.