The Debate: General vs. Specific

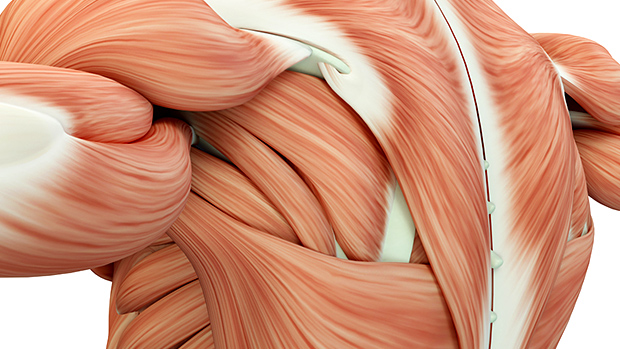

All athletes benefit from strength training for one simple reason: they need to produce varying degrees of force from multiple angles at any given moment.

Increasing an athlete's absolute strength, or the maximum amount of force a muscle can produce during a single contraction, will lead to an increase in his ability to demonstrate explosive power. But finding the right exercises to overload the specific force vector has been a bit harder to nail down.

Some strength coaches believe developing absolute strength by training a muscle through a full range of motion will translate to greater degrees of general strength and neural development. Others lean more toward using specific strength protocols designed to overload various portions of a movement pattern similar to what an athlete uses during competition.

So who's right? Well, there hasn't been much clear-cut evidence to support either approach, but a recent study is shedding some light.

This study looked at the effect of full, half, and quarter-rep range squats on sprinting speed and vertical jump ability. Researchers took 28 trained male college athletes and split them into three groups. Before beginning the study each athlete's full squat, half squat, quarter squat, 40 yard dash time, and vertical jump were tested.

Each group did four strength training workouts per week: two for upper body and two for lower body, utilizing progressive overload and periodized loading techniques for each exercise in the 2-8 rep range.

On lower body training days, group one did full range of motion squats, group two did half squats, and group three did quarter rep squats. At the end of the 16 week period each group was reassessed to determine how, or if, their training protocols translated to performance increases.

Each group increased strength in their specialized squats (full range, half, and quarter reps), but it's the impact on forty yard dash times and vertical jump that are interesting.

The group that did full-range squats did see improvements in strength by upwards of 16%, but their strength gains didn't do much for their athletic performance. In fact, the full range squat group showed less improvement than the half and quarter rep groups, boosting vertical jump height by less than 1% and only decreasing forty yard dash time by .09 seconds.

The half-squat group did show similar increases in strength to group one, but they also showed significantly greater improvements in sprinting speed and vertical jump than the full rep range group.

However, the most shocking findings occurred in the quarter rep group. Not only did they increase one rep max strength by nearly 12%, they also increased vertical jumping ability by over half an inch, and decreased their forty yard dash times by an average of .41 seconds.

So why are quarter squats better at improving sprint speed and jumping ability than full and half squats?

The range of motion used during quarter squats is much more similar to the natural range of motion used in a full sprint. And if increases in strength lead to greater force production and more explosive power during athletic movements, there would seem to be a likely correlation between getting stronger in an exercise that mimics the natural range of motion used during sprinting and jumping.

Athletes looking to add quarter squats to their training should do so as a part of a periodized program that uses strength-based training protocols during their offseason. Saving heavy strength training work for the offseason allows for a more targeted focus on overall improvements in performance, as opposed to in-season training which should be mostly geared toward maintenance and facilitating recovery from practice and competition.

- Rhea MR et al. Joint-Angle Specific Strength Adaptations Influence Improvements in Power in Highly Trained Athletes. Human Movement. 2016;17(1):43-49.