I always write the introductions to my articles last. I never know where an idea is going to take me. This particular article is the hardest – and the best – that I've ever written. It's full of emotion and brought me back to a time that was both incredibly fulfilling and incredibly hard.

What you're about to read is about playing football, but the fact is it's about something much bigger. It's about dreams, and what it takes to make them come true.

Because everybody has dreams – dreams are easy. You don't even have to close your eyes to imagine yourself winning the Superbowl, or climbing Mount Everest, or finally buying Mom the house she always wanted.

But the road between dreams and reality is much harder. It's rarely short or without obstacles – it's usually a long and complicated path filled with enough setbacks and self-doubt that would make most turn back, siding with the naysayers who told them that their goal was "unrealistic" or "impractical," or "childish" or "stupid."

Or just a dream.

Growing up in Illinois, I had one dream: to play Division I football. It wasn't the NFL – it was suiting up on Saturdays and playing for a big time school. I don't know when the dream started, but I can't tell you when it wasn't a goal of mine.

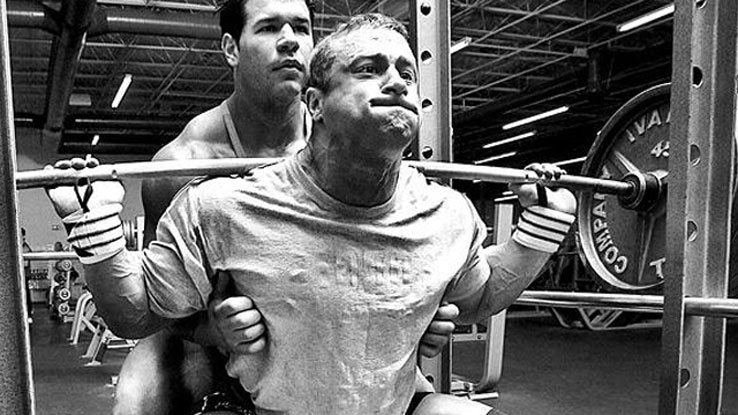

I punished my body for years in the weight room, on the track, and on the field all for one goal. I didn't ask too many questions with training; Walter Payton ran hills? Jim Wendler would run hills. Barry Sanders squatted? Jim Wendler would squat until his legs fell off.

I did so without contemplating overtraining (this didn't exist) or counting carbs. Asking questions felt like a waste of time, time that could be spent running and squatting.

Since then I've been through harder things, like divorce, children, and the death of loved ones. But at the time this was the biggest thing in my life, and the hardest. It's been over 15 years and I still look at those experiences and draw strength and wisdom from them.

When I went to the University of Arizona, I was two years removed from high school. I spent the first two years playing ball at the United States Air Force Academy (this was pre-tattoos and pre-beard) and realized that military life wasn't for me. I also realized that I needed to pursue what was in my heart.

So I left – literally packed one bag and flew to Tucson, Arizona without knowing a soul or having a guarantee that I was going to make the team. Below is what transpired and (I hope) is a guide for the young players that have the same dream I once had.

You may or may not have a choice of where you go to school. Financial and geographical restrictions may limit your choices to one or two. But if you have a choice, I highly recommend looking at schools with a good program for walk-ons.

While it may be easier to simply ask players for input, it isn't realistic. What I did was get the football media guides of each school and read the player bios. Saw which contributing players were walk-ons and who received scholarships. If possible, visit the schools and try to meet the recruiting coordinator (or any coach that will see you).

Assuming you have choices, choose the school that you feel most comfortable with. Remember that you will be a student, an athlete, and part of a community. This is a four or five year commitment on your part so make sure you're happy with your decision. Remember that your parents aren't going to the school, you are. So don't make a choice based on what they want.

If you don't have much of a choice, you're going to have to make the school and program work for you. You'll have to adjust and change your attitude to make your success.

Unless you're a preferred walk-on, you'll have to go through a tryout. This involves a coach and some graduate assistant coaches taking you through a variety of drills and football specific stuff to see who can play. If you have a modicum of talent, preparedness, and speed, you'll be fine.

I've seen many players show up to these things out of shape and with a carefree attitude. This is a good thing, as it will allow you to shine. If they want to piss on their opportunity of a lifetime, so be it. Show them up and shine.

Preparing for this is easy – be fast, strong, and in-shape. Don't take the summer off and fart around with high school friends that you won't care about in two years. That part of your life is done, and if they want to "go out with a bang," tell them you want to "go in with a fist of hate." People may see this as cold. I see this as part of achieving your greatness.

This can't be stressed enough – the one thing that's going to carry you through all the tough times as a walk-on (and in life) is your attitude. Every self-help guru has their own version of being a positive person; mantras to help you keep going through life and succeed.

I've always had a chip on my shoulder. I always feel that it's me against the world. I'm not good enough, strong enough, smart enough, or anything "enough" to adopt a happy-go-lucky attitude towards success. It's always a battle for me. This can be draining at times but this is how I can overcome obstacles – with a drive that I have something to prove and nothing to lose.

This may not be what gets you out of bed every morning, raring to tear life's head off. But whatever does get you out of bed, you have to harness it and live it. You know the saying, "Get knocked down seven times, but get up eight"? I prefer to get up eight times and knock the fuck out of whoever knocked me down the first seven times.

Adopt a winning attitude that understands you will fail but allows you to achieve your goals.

If possible, have someone in your life that won't coddle you, but call you out on your bullshit. Whenever I faltered from this attitude my father set me straight.

- Complained about school? Suck it up and study.

- The coaches won't look at me? Quit crying and get better.

- I don't like my job! Change your attitude or quit and do your own thing.

- I don't make enough money! Find a way to make more.

People tell me I'm too blunt and "mean" when I answer training questions. Be happy it's not my father answering them.

Let's get this out of the way – being a walk-on at a major college sucks. One hundred percent of walk-ons were good or great high school football players and used to being the Big Fish. They got the cheerleaders, the press, and the notoriety that comes from being an athletic stand out in high school.

This all changes when you're a walk-on. If you're expecting any of the perks that you once had, you're in for a very rude awakening.

The coaches won't respect you, many of the players won't respect you, the strength coaches will look at you as a burden, and the equipment managers will hand you the worst equipment they have in hopes of driving you out of their office. I've been handed cleats that I wouldn't have worn in Pee Wee football – heavy, molded high tops that had more in common with Herman Munster than Tom Rathman. I actually had to go out and buy cleats when I was in college.

I've heard what coaches say about walk-ons – some even had the decency to say it to my face. "You'll be lucky to see the field from the stands," and other gems of positive encouragement. I've heard strength coaches laugh and go back into their offices when walk-ons come into the weight room. I'm positive that few coaches will ever bother learning your name.

You might get a real number the first couple of years, but many times you and a fellow walk-on will have the same number. So there might be two number "34"'s on your team, neither with your name on the jersey.

While at Arizona, the walk-ons had a separate locker room. Old school cage lockers stuck inside a utility room/boiler room/storage room. When one of us got called up to the Big Locker Room, we were all happy for him (there's a huge sense of camaraderie amongst walk-ons), but we couldn't help but be a little jealous. If you weren't, you didn't have the right attitude.

There's an old saying, "Show me a good loser and I'll show you a loser." Instead of bitching about it and pouting, most of us put our heads down and worked harder – that's how you properly channel setbacks and challenges. You're either a man of action or a bitch.

Remember that your role as a walk-on, especially in the beginning, is really nothing more than a tackling dummy. And your job can literally be taken by a "dummy," a large foam bag covered in vinyl that has handles for the coach to hold.

You'll run countless plays, the same plays, repeatedly, and your body will be bruised, battered, and your head will ring. All so your teammates get a "good look" at the opposing teams plays and formations.

You think a 250-pound linebacker hits hard? Wait until his coach berates him endlessly and said linebacker knows exactly where the play is going. I've been hit so hard in the head that my dick hurt. Literally felt like my junk was smashed by a vice due to a facemask being applied to my ear hole.

And when practice is over, the rest of the team goes for the Team Meal while you trek back to your room for ramen noodles and RC Cola. You couldn't feel less a part of the team at this point. But that's the way the world works, and something very valuable I learned from all this is that you don't get treated fairly, nor should you.

The idea of fairness is a ridiculous notion – if you have something to offer then you should be treated as such. If you're a scrub in life, don't expect to be treated like someone that has value.

If the star of the team – the guy that makes the plays and makes the team go – is late to a meeting, it's brushed off. If you, the scrub tackling dummy, are late, you'll get booted out of the meeting and you'll be running after practice (that is if they care enough to stay late and waste their time with you).

There are two kinds of people in the world: the ones that protest and complain and want fairness despite never having earned it, and the ones that fight their asses off to be important and make a contribution. You have to earn the right to be treated fair. The people that have a problem with that are the scrubs.

If you take one thing from this article, let that be it.

As a walk-on you have few opportunities. So you'd better take advantage of the few that you get. You'd better be physically and mentally ready. The physical part is easy – just train. Any idiot can run and lift.

But you better know the plays and know your assignment. Nothing pisses a coach off more than a mental error. So while you may get frustrated and not bother with the playbook, being ignorant of the plays will get you in the doghouse quicker than shit through a goose.

At Arizona we had a Scout Bowl every Thursday. While the rest of the team had a light, half-pad walk through, the scrubs played in a controlled scrimmage. This was the one way that many of us had to showcase our skills.

However, there are a lot of scrubs and a lot of redshirt scholarship players, and the latter will always get playing time in the Scout Bowl. So even in your own game you may not even get to play.

One Thursday I got my opportunity. The redshirt scholarship players showed some prima donna attitude and didn't want to participate. Coach Dino Babers looked at me, asked me if I was ready and put me to work.

The good/bad thing about Scout Bowls is that the offense is run heavy – it's hard to get the passing game down when the receivers and quarterbacks don't practice together. There's no timing and these two positions need to have some practice time to get this down.

So while this is a good thing for a running back (more carries), it also allows the defense to stack the box and stuff the run. I must've carried the ball 20 times in a row with varying levels of success and I was dead tired. My head was cut open, my eyes stinging with blood and sweat, my nose busted, but there was no way in hell I was ever coming out. I knew this was my one opportunity. This was it.

After that Thursday, I played in every single Saturday game. That was my opportunity. I had no idea it was coming when I woke up that Thursday morning, but if I hadn't showed up to play I probably would've never seen the field. The coaches saw something in me that day and my life changed.

As a walk-on, you'll have to find your own "Scout Bowl" moment – the time when you're called out to do something, anything. If you waste it and squander it by not being ready, that's your own fault. So be prepared.

For many, this is going to be a hard pill to swallow. In high school, I was the starting tailback and outside linebacker. I never came out of the game. I ran with abandon and averaged over 100 yards a game on fewer carries than any running back. I ran hard and through people.

When I got to Arizona I had to come to grips that I was not going to play that role. I had to contribute where ever I was needed. Since I was slow, I had to gain some weight and play fullback. And this was in an offensive system that didn't use two backs frequently.

So put your ego aside and know that your role as a football player may change. You're going to have to be fluid – you may have to learn a new position if you want to get on the field. It may be a position that doesn't get the playing time or the glory that you're used to.

The important thing is that you make yourself indispensable at what you do. Work as hard as you can to be the best at your given role. If that's protecting the punter, do so with such precision that no one can take your job. Do not take your job for granted. Make it hard on the coaches to take you out. Fight like hell to do your job better than anyone.

Despite all the bad shit that you go through, in the end, the good always outweighs the bad. There's nothing more satisfying than running onto that field after years of work. The people in the stands have no idea what you've gone through to get there. You're just a guy in pads, identity shrouded by a facemask and a number.

Who cares? Most don't know what it's like to dream your entire childhood for a single moment, then work thousands of hours through endless setbacks just to see it happen.

Some people might see it as luck (and there is some involved), but what they don't see, nor do they ever want to see, is the blood, sweat, pain, and early mornings that you persevered.

They don't want to see it simply because they don't want to know that their failures in life stem from not wanting to deal with being uncomfortable, taking a chance, failing time after time, and putting it all on the line.

I'm going to brag a bit here and I don't care. I had two defining moments in my college career, two things that I'll never forget.

My first carry ever went for a touchdown on ESPN.

It was a Thursday night Game of the Week on ESPN. This was the only game being played that day. We were playing San Diego State in San Diego.

I believe it was the second quarter and we were on the 5-yard line. Keith Smith, the quarterback, got the call and looked at me. "Are you ready?" The call was "5-2," a simple fullback dive. The only thing I remember is diving into the end zone, jumping up and looking around for the ref's signal.

After seeing his two arms raised I began celebrating. And celebrating. And jumping, and more celebrating, so much so that the ref came over and threatened to flag me for excessive celebration.

Fuck it – this was real and genuine. I sprinted off the field and was greeted by Keith Smith, who jumped and hugged me and I about took his arm off giving him a "high five."

It wasn't about the six points. It was the work to get there and the happiness that my close teammates felt. After the television break, I got the sideline camera and did the obligatory "Hi Mom and Dad!" even though they were at the game, and thanked my girlfriend at the time, and my dog, Betty. Yeah, I thanked my dog on national TV – just because no one else did. No one understood it except the friends who were watching and they laughed because they knew how ridiculous it was.

The next day, I walked in the weight room to lift and the whole staff started clapping and hugging me. These were the people I'd spent countless hours with and with whom I had a great bond. Seeing them so happy was amazing.

That weekend, my good friend Matt Rhodes (also a walk-on) threw me a huge party at his sister's apartment complex. There were tons of people and drinks and Matt kept introducing me, "This is Jim Wendler. He's a star football player and scores touchdowns. You might want to sleep with him."

My second defining moment came at the end of training camp, when scholarships for walk-ons are announced.

This was a big deal for us, and it's not about the money. It's about the respect of the coaches and players. You can always make money but you have to work to earn respect.

When the head coach, Dick Tomey, announced my name at the end of Two-a-Days my senior year, I cried like a little girl. I ran back and called my parents and cried in the phone. I thought about all the injuries. The Graves disease. The critics. The years lifting and running. The concussions.

Every second was worth it. This was something I earned through years of work. No one could take it away.

When I watch college football today and hear an announcer talk about a walk-on, it brings back a lot of memories. This was an amazing time in my life and one that I continue to look at and remember when I need a boost or an attitude check.

Most of all, I hear that announcer say "walk-on" and while I know he's giving respect, from experience I can tell you that I'd rather be known as a football player, not as a walk-on. That is the ultimate respect.

- Please pass this on to your sons if they hope to play college football but may not be scholarship material.

- Please post this on your bedroom wall if you're a high school player who has a dream like I did.

- Please post this in your weight room if you're a high school coach who wants to encourage your players to achieve something more, even if the "scouts" are telling them otherwise.

Good luck to all of you with a dream and the balls to fight for it. You won't need it, though.