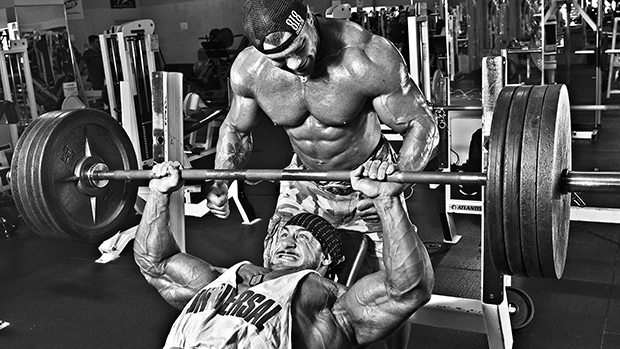

Powerlifters, strongmen, and bodybuilders – while they may follow vastly different training systems, the successful among them have one thing in common: they all have above-average levels of muscle mass.

Powerlifters and strongmen are mammoth-like, usually with high levels of muscle mass combined with similar levels of body fat, a result of their overall focus on performance over aesthetics.

Bodybuilders, on the other hand, typically have even greater levels of muscle mass than their strength-focused relatives but lower body fat levels, and a balanced, muscular physique indicative of the aesthetic focus of their training.

Each group has different approaches to decidedly different athletic pursuits, yet similar outcomes in muscle size and strength. Perhaps similarities in their training might provide us with valuable insight into the optimal way to train for mass and strength development.

Three recent surveys tried to shed some light on how bodybuilders (1), powerlifters (2), and strongman (3) develop superhuman strength and muscle mass.

The expected differences in their training were all there. Bodybuilders love to use five-day training splits, emphasizing body parts over movements, and focus more on the overall volume of their training than the load.

Powerlifters on the other hand, love box squats, bringing toys to the gym (bands and chains), sniffing ammonia, and seeing just how many plates they can cram on the bar.

Strongmen land somewhere in the middle, hoisting stones, kegs, and any odd object they can get their hands on, but also focus on the big three power lifts (bench, squat, deadlifts) while also incorporating Olympic lifts (clean and jerk, snatch) into their training.

The differences between their programs would make for a long list, but after sifting through the studies what's most apparent is that despite the differences in their respective sports, all the athletes rely on multiple training intensities (%RM) in their strength training sessions.

While it's common to see rigid intensity guidelines for what constitutes hypertrophy or strength training (4), it seems that none of these high-level athletes actually follow this advice.

Recent research suggests that hypertrophy can occur following training at opposite ends of the loading continuum, using what would be considered heavy (80-90%-1RM) and light (30%-1RM) training loads.

In their initial study, Burd, et al. (5) demonstrated that the muscle protein synthetic response to a single bout of strength training was similar with either heavy (90%-1RM) or light (30%-1RM) training loads lifted to failure.

In fact, the authors found a sustained synthetic response of specific protein fractions (sarcoplasmic, myofibrillar) with light loads, suggesting that a case could've been made for the potential superiority of lighter training loads lifted to failure for muscle hypertrophy.

Unfortunately, what happens following a single strength training session is not necessarily representative of the ultimate adaptations to training (hypertrophy), so the authors followed their original study with a 10-week training program comparing 30% of 1RM for three sets against 80% of 1RM for three sets, and 80% of 1RM for one set.

Mitchell, et al. (6) took 18 recreationally active men and had them perform a three-day per week unilateral strength training program for the knee extensors, with all sets taken to concentric failure.

Not surprisingly, based on their earlier study, training to failure with 30% of 1RM for three sets per exercise produced similar (but not greater) hypertrophy as training with 80% of 1RM for three sets, albeit with smaller changes in 1RM strength.

Some may use this study as an excuse to take some plates off the bar when training for size, and that may be a good idea in populations concerned with the forces involved in exercise (i.e., elderly, injured, musculoskeletal disorders), but what about those looking to improve their performance and muscle mass? Have we all been wasting our time straining under heavy weights?

Definitely not. These results highlight that both methods of training are useful and effective. In fact, it's not load or time-under tension that's most important, but the relationship between them that matters most.

This suggests that optimal hypertrophy training shouldn't rely on a single training intensity across all exercises, but rather address both heavy and lighter training loads based on the characteristics of the exercises used.

In the previous studies, higher training loads produced similar hypertrophy as the low load condition, but with a fraction of the time spent under the bar (roughly 15 seconds per set versus 45 seconds with 30% of 1RM).

Lighter weights required much more time with the weight to produce a similar amount of hypertrophy. The argument in favor of heavy weights is that high loads maximize muscle recruitment, suggesting that using as much muscle mass as possible is ideal in hypertrophy training.

We know that load increases muscle recruitment, and more weight on the bar means you need more muscle to move it. Henneman's size principle states that motor units (muscle fibers and the motor neuron that innervates them) are recruited in an orderly fashion dependent on the size of the motor unit (smallest to largest) (7,8).

Physiological principles are rarely set in stone, and luckily for us we can bend the rules to allow us to recruit as much muscle as we can without worrying about how much weight is on the bar.

One of the main limitations of lifting light loads compared to a near maximal effort was that according to the size principle, you'd only recruit the smaller motor units and fail to tap into your higher threshold, large motor units (typically fast twitch fibers).

But fatigue breaks the rules (9). If you continue to lift a light weight, fatigue inevitably sets in, and as it does something interesting happens. As you start to struggle, your nervous systems tells your muscle to use more motor units to ensure you can still lift the weight, and eventually taps into those larger, high-threshold motor units.

Researchers hypothesize that it's this fatigue-related recruitment that allows low-load training to still recruit lots of muscle, and that this may be involved in hypertrophy (10).

Based on the survey data above, we see that those with the most muscle have been successfully exploiting multiple training loads despite what science has to say about it. Each group relies on multiple training intensities, but changes the emphasis of the work in the program based on their chosen sport.

Bodybuilders emphasize bodyparts and high volume work, but still capitalize on high-load (1-5RM) compound exercises. Powerlifters emphasize heavy weights and the big three movements (bench press, squats, deadlifts), but don't be surprised to catch them training in higher repetition brackets and focusing on muscles over movements for the assistance exercises.

They may not have had science there to help, but through a long process of trial and error eventually figured out the relationship between load and time under tension and how to capitalize on it to increase strength and muscle mass.

Just because we've borrowed from different athletes doesn't mean our training will be a disorganized mess of all the favorite exercises of strongmen, powerlifters, and bodybuilders combined.

Rather, each workout will feature an organized progression of exercises incorporating different loading ranges based on the specifics of the exercises with the following template:

- Strength/Power Compound Movement: These are the movements in the 1-6 rep range, that when done effectively (ramping intensity followed by sufficient warm-ups) will recruit those high-threshold motor units discussed earlier.

- Mid-Range Compound Movement: Something like a seated row, machine press, or hack squat in the 8-10 rep range that allows one to focus more on the muscles than the movement.

- High-Rep Isolation Movement: Movements in the 12-20 rep range that let us use a much lighter load, but fatigue the muscle toward the end of the set. Leg extension, cable biceps curls, and pec-dec flyes are good choices here.

Using the template above, we can easily construct a training day that maximizes muscle recruitment with a blend of heavy compound exercises and lighter isolation movements emphasizing fatigue.

In the sample back/biceps training session (see below), all repetitions ranges are addressed as we move from a heavy compound exercise (deadlifts) to single-joint isolation exercises (biceps curls).

Sample Program

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | Rest | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Deadlift | 4 | 4-5 * | 3 min. |

| B | Weighted Chin-Up | 4 | 8 | 90 sec. |

| C1 | Band-Resisted Push-Up | 5 | 12-15 | |

| C2 | Seated Row | 5 | 15-20 | 60 sec. |

| D | Barbell Biceps Curl | 4 | 15-20 | 30 sec. |

* Working up to a top set of 4 or 5

Powerlifters, bodybuilders and strongmen are specialists, but by borrowing elements from their respective domains we can elevate our performance and learn to train like the best.

Better still, it's no longer an either/or equation – you can do the compound exercise you know you should do, and still hit the isolation exercises you're ashamed to admit you love.

If you're looking to optimize your hypertrophy training while taking your strength to new levels, use the following guidelines in your training:

- Perform compound and isolation exercises: Compound exercises are great, but there's still room in a balanced training program for isolation exercises. The majority of powerlifters, bodybuilders, and strongmen rely on a diverse selection of exercises and so should you.

- Prioritize major compound exercises: Compound exercises (squats, deadlifts, etc.) use multiple joints and lots of muscle mass but require focus to ensure optimal coordination to maximize strength in the lift. Hit these exercises early in the session to ensure you have both the mental and physical capacity required to prioritize strength and get the most plates on the bar.

- Use multiple repetition ranges: If you've included a mix of compound and isolation exercises in your program, vary your repetition ranges to emphasize load on your multi-joint lifts like squats and deadlifts (1-5 RM) and higher-repetition ranges on your isolation, single-joint exercises like curls (6-12 RM).

- Emphasize fatigue on isolation exercises: Isolation exercises often involve a single joint, use less muscle mass than compound exercises, and are not well suited to high load training. Perform these exercises in higher repetition ranges and make sure you use a training load that fatigues the muscle by the end of the set. Try to make those light weights look heavy.

Optimal hypertrophy training was never compound or isolation, heavy or light weights, lift slow or fast, but rather integrating all these techniques into a cohesive program.

While it may seem like a lot on paper, following the tips above will have you well on your way to a strong, muscular physique reminiscent of the world's biggest and strongest.

- Hackett DA et al. Training Practices and Ergogenic Aids used by Male Bodybuilders. J Strength Cond Res. 2013 Jun;27(6):1609-17.

- Swinton PA et al. Contemporary Training Practices in Elite British Powerlifters: Survey Results From an International Competition. J Strength Cond Res. 2009 Mar;23(2):380-4.

- Winwood PW et al. The strength and conditioning practices of strongman competitors. J Strength Cond Res. 2011 Nov.;25(11):3118-28.

- Kraemer WJ et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009 Mar;41(3):687-708.

- Burd NA et al. Low-load high volume resistance exercise stimulates muscle protein synthesis more than high-load low volume resistance exercise in young men. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(8):e12033.

- Mitchell CJ et al. Resistance exercise load does not determine training-mediated hypertrophic gains in young men. J Appl Physiol. 2012 Jul.;113(1):71-7.

- Henneman E et al. Excitability and inhibitability of motoneurons of different sizes. J. Neurophysiol. 1965 May;28(3):599-620.

- Henneman E et al. Functional Significance of Cell Size in Spinal Motoneurons. J Neurophysiol. 1965 May;28:560-80.

- Adam A et al. Recruitment order of motor units in human vastus lateralis muscle is maintained during fatiguing contractions. J Neurophysiol. 2003 Nov.;90(5):2919-27.

- Burd NA et al. Bigger weights may not beget bigger muscles: evidence from acute muscle protein synthetic responses after resistance exercise. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012 Jun.;37(3):551-4.