You attend training seminars to hear the experts lecture about fitness, but the real value is often found in the hallways between presentations. There, you get to eavesdrop on what the experts are really thinking about. Ideas flow freely, and no one is asking to see the studies.

That's why we like these compilations. You get an insightful peek into how several experts answer the same simple question, just like in the hallways at the seminars. Here's this month's question:

What are most dedicated lifters missing in their training?

Here's how our experts answered it:

The lifting game is often about numbers: the weight on the bar and the weight on the scale. Most men want to see both go up. They want to be strong and they want to be big. And for many years, that's a fine goal.

The potential problem? For the experienced lifter with a couple of decades under his belt, those numbers eventually start to work against him. Once he's close to his natural genetic limit, the heavier one-rep maxes create more pains than gains. And the growing scale weight? Yeah, that's probably fat.

What we're left with is a hoard of over-fat middle-aged men with various cardiovascular problems percolating and silently brewing in their bodies.

At this stage, most of us need to shift our mindsets. Instead of trying to add 10 more pounds to that bench press – a left-shoulder screaming, butt-lifting "PR" – maybe we should focus on other, more beneficial goals. Instead of adding another 5 pounds to the bathroom scale, maybe there are other numbers that are more important.

Those new numbers may include your blood pressure, resting heart rate, and waist measurement. All should go down. That's your new PR.

You don't have to give up heavy lifting, but your primary goal now is to get metabolically conditioned. Your heart is your new favorite muscle to train. You flex it by not having a heart attack or a stroke. Really, chicks dig it.

Bonus: You'll look better naked too. – Chris Shugart

I once had dinner with Prince Albert of Monaco. This was in Calgary during the world bobsled championships when the Prince was a team member. He was, as you might expect, accompanied by a couple of bodyguards, one of whom told me he knew 17 ways to kill a man with just a pencil.

John Wick? He probably only knows just a couple – you know, puncturing the neck or the eardrum until they spurt like the Trevi Fountain in Rome. Anyhow, the Prince's bodyguard really knew how to make good use of a pencil.

I only wish more people in the gym would use one.

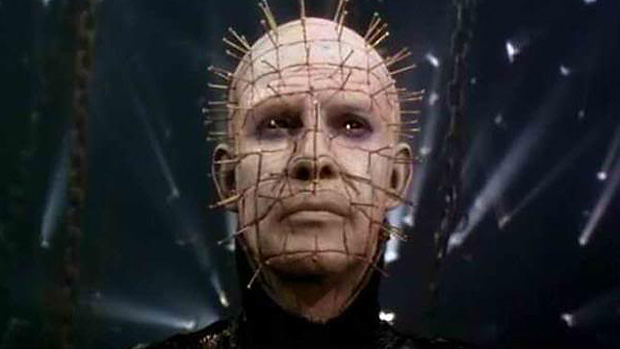

Let me explain. Prior to COVID, I'd worked out at the same gym for nearly 20 years, and in all that time, I honestly don't remember anyone ever looking better, or much better, physique-wise. Sure, plenty of guys could jump onto really high boxes or flagellate the floor with battling ropes so hard they made that albino guy in The DaVinci Code look like a Russian babushka doing some spring cleaning. Still, these accomplishments never seemed to add any noticeable muscle.

Wait, I take it back. I saw one young girl make some phenomenal changes in a very short time span. For years, she was a die-hard anorexic. It was so advanced that her body was covered with lanugo, the soft, downy hair that often grows on anorexics to insulate their fat-free bodies against the cold.

Anyhow, for some unknown reason, she decided to pull a 180 and go from one extreme to another and become a powerlifter. Within two months, she went from Gollum to Gimli. I can only guess that her calorie-deprived body went nuts when given some extra food, and she ballooned up to proportions that were as attention-grabbing as her previous state. Strangest thing I ever saw in the gym.

So yeah, that's one strategy to put on muscle, but that brings me back to pencils. Pencils let you write down your programs. Pencils let you record your poundages and reps. Pencils let you chronicle your rate of perceived exertion. Pencils let you record your progress.

Maybe you have an eidetic memory like Sheldon from "The Big Bang Theory" and can remember all that without recording it, but most of us aren't so lucky. We have to write things down. If we don't, most of us just stay in the same poundage and rep zone forever. Hardly anybody in my old gym did any of that, hence their lack of progress.

I'm aware that a shit-ton of people prefer instinctive training, but practically the only people I saw make progress with that method were pro bodybuilders who didn't need to follow that much structure because their drugs gave them carte blanche to ignore the tedium of chronicling their workouts. Anything they did added muscle. Not so with the rest of us mere mortals.

So dedicated lifters should use a pencil, not as a weapon, but as a muscle-building tool. – TC Luoma

Dedicated lifters are often stuck in their ways. You might do the same exercises every week because you enjoy and excel at them, but that also makes you crappy and weak at the exercises you've chosen to forget.

Remember, you're only truly strong when you lack weaknesses. If you're an experienced lifter who's hit a plateau, one of the best things you can do is more of the stuff you avoid, like single-leg work, weighted pull-ups, inverted rows, rotational work, frontal plane exercises, and some of the more "foo-foo" stuff to protect your shoulders and spine, like this:

If you think you've got strong shoulders, see what you think after these. Start light! – Gareth Sapstead

Good routines performed for too long often turn into ruts. What once worked may no longer be serving you. It may even be causing pain. Maybe barbell exercises don't agree with your joints anymore, where a dumbbell or a machine would feel better and allow for more tension with less fatigue.

Being adaptable means keeping an open mind about training and recovery modalities that might help you avoid (or manage) injury and allow you to keep training every year.

If you're a bodybuilder, this doesn't mean you have to suddenly quit and turn to yoga, but maybe just extend your warm-up and do some targeted mobility drills. These practices make heavy lifting feel better.

Maybe take an extra day off, or add a little more cardio to compensate for not being on your feet as much. Adapt as life and work changes. Seek out a skilled coach or physical therapist to break out of dysfunctional patterns and offer guidance.

Get out of rigid training and nutrition ideologies so you can feel things out and find what works for you now. Even if you believe you're open-minded, consider regularly running a diagnostic on your approach toward training, nutrition, and recovery. – Andrew Coates

The most dedicated lifters often lack objectivity. They're extremely passionate when it comes to training, which is good because it makes them work hard and be consistent. But their drive often acts as a blindfold when it comes to their recovery:

- The amount of training they can positively adapt to

- The number of rest days they need

- How tired they are

- When they should back off during a session

- When they should deload

They also tend to not be very good at evaluating where they are now, where they want to be, and what they need to do to get there.

Passionate people are extremely emotional and tend to make emotional decisions. This increases the likelihood of "program hopping," not so much because they're unsatisfied with their plan but because they easily get excited when they see a new cool approach. They're also easily seduced by shiny new exercises and often lack the objectivity to know if those exercises are right for them.

Listen, being passionate is a great weapon to help you reach your goals. And when you start your workout, you should absolutely use that weapon. But you're likely going to be your own worst enemy when it comes to gaining unless you find a way to use objective measures to control the amount of training you do.

I'll use myself as an example. I'm driven by passion when it comes to training. Before developing more objectivity, I was as excessive as one could possibly be.

I used to train for weightlifting (snatch, clean & jerk) and, for a while, trained at the national center. Our coach had a weird way of programming: he wouldn't plan a number of sets per exercise. For example, he'd give us: the exercise (snatch), reps (3), the intensity zone (80-85%), and duration (20 minutes). Then we'd do the number of sets we felt good about doing during that timeframe.

As an excessive person, I'd get 10-12 sets in. One of my partners, who out-lifted me on each lift and was a World Championship team member, would do about 3-4 sets in that timeframe.

It frustrated me to no end. In my mind, I was training three times as hard. In reality, I was burning myself out while he was positively adapting. When you're passionate, the two hardest things to do are:

- Avoid doing too much (volume or frequency)

- Sticking with the plan

Be aware of those issues and find objective measures to make sure you avoid these behaviors. – Christian Thibaudeau

Even dedicated lifters need more horizontal pulling (like rows) in their training. There are three reasons:

1. To reinforce shoulder stability.

Shoulder injuries sideline more lifters than anything else. By building up your lats, traps, rhomboids, and posterior chain, you provide more support for the shoulder complex. Use a 2:1 horizontal pull-to-push ratio as a bare minimum. Horizontal pulling is superior to vertical pulling (pull-ups, pulldowns) for shoulder health due to most lifters' shoddy overhead mobility and the internal rotation role the lats play with pull-ups and pulldowns.

2. To combat computer guy posture.

We live in a sedentary society full of people addicted to their screens. Spending all day with rounded, internally rotated shoulders reinforces poor posture that tightens your pecs, restricts shoulder mobility, and makes you appear smaller and less confident. Combined with years of unbalanced training, you have a recipe for long-term shoulder dysfunction.

3. To build a V-tapered physique.

Because the majority of lifters have unbalanced training, their physiques are similarly lacking. By increasing horizontal pulling volume, you'll provide the stimulus to add lean muscle to your traps, lats, rhomboids, rear delts, forearms, and biceps. Emphasizing more horizontal pulling will help you build a V-tapered physique and fill the gaps on your backside.

How do you incorporate more horizontal pulling?

First, emphasize a horizontal pull after a pressing movement. You don't need to push the intensity hard and split your spleen with Pendlay rows between bench presses. Just use a variety of band pull-aparts and inverted rows after your "push" exercises. The goal shouldn't be to annihilate your back, just get a light pump.

Second, before starting your main workout, perform 50 reps on an inverted row. Rotate hand positions (pronated, neutral, supinated) and implements (barbell, TRX, rings, etc.).

Break up your sets however needed. Over time, this volume adds up to improve your posture, protect your shoulders, and build a V-tapered physique. – Eric Bach

If you're not assessing, you're guessing. Movement pattern assessments will help you discover deficient areas in mobility and stability. Finding inefficiencies will help you get stronger, lift longer, and stay healthier. It's a nonnegotiable of any advanced lifter.

If you identify a lack of internal rotation in your shoulders, then work on it. Your bench press may go up significantly. If you identify that your hips are lacking mobility, then work on them. Your squat will improve, and your knee pain will go away.

Here are a few examples of movement pattern assessments. Score yourself.

Shoulder Flexion/ External Rotation

Use this pattern to assess the shoulder's external rotation, flexion, and abduction. It also gives us a glimpse of scapular and thoracic mobility.

What to look for:

- Fingers reach spine of opposite-side scapula

- Smooth coordinated movement

- No compensation by shrugging the shoulder

Shoulder Extension/Internal Rotation

Use this pattern to assess internal rotation and extension.

What to look for:

- Fingers reach inferior border of the opposite side scapula

- Smooth coordinated movement

- No compensation in the spine, scapula

Multi-Segmental Flexion

Use this to test normal flexion in the hips and spine. This test gives us a general glimpse of hip function and posterior chain flexibility.

What to look for:

- Posterior weight shift

- Touching the toes

- Uniform curve of the lumbar spine

- No lateral spinal bending

Multi-Segmental Extension

Use this one to test for normal extension in the shoulders, hips, and spine.

What to look for:

- Bodyweight shift toward the front of the feet

- Symmetric spinal curves

- Spine of the scapula must clear a vertical line drawn from the heels

- Arms/elbows in line with the ears, 180 degrees of shoulder flexion

Squat

Use this to assess bilateral, symmetric mobility and stability of the hips, knees, ankles, and core.

What to look for:

- Achieve depth parallel to the floor

- Head and chest face forward

- Heels stay in contact with the floor

- Make a note of optimal feet width and positioning

Hip Hinge

Do this to see your ability to hinge at the hips in isolation while maintaining a neutral spine. It's different than a squat. With a squat, we have a knee bend and hip bend. Hip hinge just focuses on the hip joint itself.

What to look for:

- Spine remains neutral

- Posterior weight shift

- Motion comes entirely from the hip joint

Lunge

Do this to test lateral stability and simulate dynamic deceleration with balance.

What to look for:

- Knees stay in line with toes and hips

- Head and chest face forward

- Smooth coordinated motion

- Knee can translate forward towards the toes

- No loss of balance

Outcomes of your movement assessment:

Acceptable/Functional: Movement is good enough to allow you to be cleared for activity without an increase in injury risk.

Unacceptable/Dysfunctional: Movements are dysfunctional, and you may be at risk for injury unless movement patterns are improved.

Painful: Movements produce pain. Currently injured regions require additional, more advanced movement and physical assessment by a qualified provider. – Dr Dale Bartek