You've probably heard this phrase: "World records are broken by athletes who are in pain."

Even if you haven't, it's no surprise to coaches, athletes, or serious sports fans. We all know athletes play with pain.

However, being aware of it and understanding what you can do about it are very different things. To put it bluntly, the strength and conditioning community is still very much in the dark when it comes to understanding how pain affects the body, and how individuals like you can effectively reduce or eliminate that pain.

It's not that they're wrong when they recommend sensible solutions, like more balanced strength-training programs, soft tissue work, and mobility protocols. Those techniques are extremely effective, and I've produced my own DVDs on those very subjects.

The problem is this: they aren't enough to deal with physical pain and dysfunction. There's still a major component to dealing with pain – and to making gains in your training despite pain – that's been left out. Until now.

Before I get into that missing piece of the puzzle, I want to make it clear that I'm talking about chronic pain. I'm absolutely not talking about acute injuries or direct trauma. If you have pain in your back from a herniated disc, or in your knee from a torn ligament, you need to see a qualified rehab specialist.

On the other hand, if you have chronic aches or tightness in your muscles or joints, this article is for you. And if you're a coach who works with athletes who complain that their knees ache or their lower back tightens up after games or workouts, please keep reading.

People like us – serious lifters, many of whom also train serious athletes – will experience two different types of pain in our careers.

Type 1 pain occurs during or immediately after high-load activities, but isn't felt when doing normal daily activities like sitting or walking. A few examples:

- A guy can walk for miles with no knee pain, but his knees hurt when he runs, plays basketball, or squats or lunges with weight.

- A guy can push his lawn mower around for hours without shoulder pain, but his shoulders hurt when he does chest or shoulder presses in the gym.

- A guy never experiences any back problem except right after he works out or plays a round of golf.

This category also includes most overuse injuries, like tendonitis and bursitis.

Type 2 pain is associated with low-load activities. A lifter with Type 2 pain might be able to squat a house without flinching, but if he has to stand for a half an hour or sit in a movie theater for any length of time, his knees get stiff and achy.

- Or his back hurts when he sits at his computer or takes long drives.

- Or he wakes up in the middle of the night with shoulder pain he hadn't felt during the day.

- Or he always feels tight in certain areas no matter how much he stretches or how much soft-tissue work he gets.

- Or maybe he can't say where he feels chronic pain, since it moves around to different parts of his body without any particular reason.

Chances are, you've experienced both types of pain, and if you're a coach you probably work with athletes suffering from one or the other. And chances are the advice you've gotten, and the rehab strategies you've used, all start with the idea that all types of pain should be treated the same way.

Which is not the case at all.

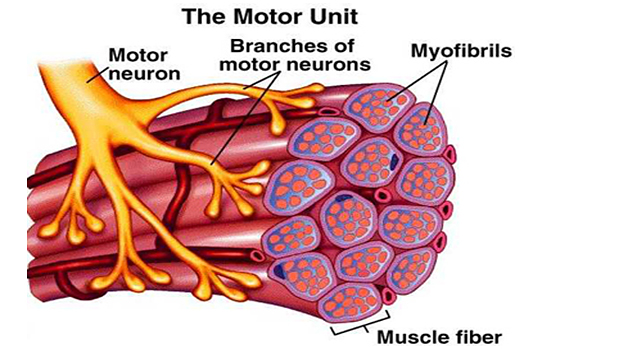

You probably know that your muscles contain millions of fibers, which are organized into motor units. A motor unit consists of a single motor neuron, plus all the muscle fibers it controls.

You probably also know that not all motor units are the same. Just to keep it simple, let's say they fall into two big categories: slow and fast. Slow motor units are easily activated and take a long time to fatigue. Fast motor units need more of a stimulus to come into play. Whereas slow motor units are working all day in the muscles responsible for posture, and handle simple tasks like walking or typing, the fast ones don't get going until you're doing something that involves at least 40 percent of your max strength and power. The tradeoff is that they fatigue faster.

I don't want to bog you down with exercise science, but before I can explain how slow and fast motor units relate to chronic pain, there are some key details about muscle function to keep in mind:

- All of the muscle fibers in the single motor unit are of the same fiber type. So a nerve that controls a slow motor unit only activates slow muscle fibers.

- Postural control and simple, low-load functional movements are primarily a function of slow-motor-unit recruitment

- You can selectively exercise the slow motor units with low-load exercises and motor-control training.

- When you do a high-load activity, like lifting or sprinting, your body recruits both slow and fast motor units.

- Those high-load activities are dominated by your body's biggest and strongest muscles, especially the multijoint muscles, which are ideally positioned for strength, speed, and a large range of motion.

So we now know that there are two general types of pain, and two general types of motor units. As you probably guessed, there's a connection.

Athletes with Type 1 pain are better at controlling muscle tissue during low-load activities, but experience problems when they shift to high-load activities. These athletes have a high load dysfunction, and that requires a high-load solution.

As luck would have it, we're really good at resolving this kind of dysfunction. Good coaches and qualified rehab professionals know how to create well-balanced strength-training programs, and we know how to prescribe mobility exercises and soft-tissue work.

In other words, just about every good training article ever written by a qualified professional can help you if you have Type 1 pain. That's precisely why this article doesn't address that issue.

Instead, I'll focus on low-load dysfunction – Type 2 pain.

If you have Type 2 pain, you tend to be fine with high-load activities; the discomfort kicks in when you aren't running fast or lifting something heavy. That means you have a low-load dysfunction – a problem with the way your body activates its slow motor units – and that requires a low-load solution.

The problem you have can't be addressed with mobility work or a foam roller. You don't need a better strength-training program, simply because the dysfunction has nothing to do with strength. It's all about the way you recruit and control your smaller, weaker, slower motor units.

In a pain-free state, your brain and central nervous system (CNS) can utilize a variety of motor-control strategies to perform functional tasks, and to give you equilibrium and joint stability.

There's no one correct order of muscle recruitment or firing pattern. Your body will simply choose the best strategy available to meet the demands of the given task or situation. A pain-free body is very adaptable.

However, when pain is present, things change drastically.

The options available to the CNS become limited, and your body ends up using consistent, repetitive co-contraction patterns, usually with exaggerated recruitment of the big multijoint muscles instead of the deeper, smaller muscles – the ones responsible for stabilizing your joints.

In other words, your body bypasses the low-load system and makes the high-load system responsible for all types of movement. This is an imbalance that will surely lead to a breakdown.

Now you understand why you tend to feel "tight" and "locked up" when you have chronic pain. It's because the prime-mover muscles are being called on to do everything, instead of just the specialized activities they're supposed to perform. Muscles that are never given a chance to rest and relax will react by tightening up.

In other words, tightness and mobility restrictions are symptoms of the problem, not the cause. If something is tight, it got that way for a reason. And the reason, as you just read, is a flaw in the motor-control system.

Now you understand why high-level athletes are able to play through pain, and sometimes play at the top of their game. Their high-load muscles can still express strength and power.

And now we get to the big question: What can we do to fix the low-load system so we, or the athletes we work with, no longer have to deal with chronic pain?

The goal of the following exercises – which are listed in no particular order – is to retrain your slow motor units. At Performance University, we call it "muscle activation training." We use them on a daily basis with our athletes to improve their low-load motor-control systems and thus enhance performance.

We call these "general" exercises, since they aren't designed to address pain at one specific joint or region. In our experience, they successfully address 75 to 100 percent of the most common motor-control deficits athletes and lifters experience in their shoulders, back, hips, and knees.

My advice: If you're going to try these exercises, don't just focus on the ones that appear to address whatever problem you currently have. Pain that shows up in one area can be a sign that your entire system needs reprogramming.

Most of you should be familiar with the bird dog. For most people, it would be considered a low-load muscle-activation exercise. It's generally non-fatiguing and based on building control, rather than strength.

Basic Technique

Maintain a neutral spine as you reach straight out with one arm and the opposite-side leg. Then pull the arm and leg back in without touching the ground. Move your limbs in a controlled tempo while breathing normally. We normally perform this exercise for 1min on each side.

Performing the bird dog on a bench reduces the

base of support and thus increases the recruitment challenge.

Inverted (Supine) Bird Dog

Lie on your back. Keep the hand of your nonworking arm between the floor and your back to make sure your lower back stays in a neutral arch throughout the exercise.

One-Inch Bird Dog

If your hips and/or shoulders "click" when they move, this variation is for you. Athletes with this type of issue, in my experience, usually have lost the slow-motor-unit ability to control their joints while they're in motion.

It begins exactly like the traditional version: You're on all fours with your wrists under your shoulders and your knees under your hips.

That's where the similarities end. Instead of reaching out with one arm and the opposite-side leg, which can end up being dominated by the high-load muscle system, you lift your arm and leg just an inch off the ground, as if they were hovering.

With this subtle movement, you pull your shoulder and hip joints farther into their sockets, helping the low-load system relearn the way to control these joints before movement. Avoid lifting the hand and knee so high that your shoulders and hips rotate and you lose ideal alignment.

Do 3 to 10 reps of 10-second holds on each side.

Upright Bird Dog

Exercises can be classified by the predominant plane of movement. A bench press, for example, involves shoulder-joint movement in the sagittal plane. A rotational exercise occurs in the transverse plane. The bird dog variations I've shown so far mostly occur in those two planes. So my colleagues and I developed the upright bird dog to bring in what's called the frontal plane.

Sit on the side edge of a flat bench with your hands on the bench alongside your hips, as if you were going to do bench dips. You want your feet on the floor, and your hips, knees, and ankles all bent at 90-degree angles. Shift your weight forward so your butt is no longer in contact with the bench and all your weight is on your hands and feet.

Now lift one leg and the opposite-side arm without changing the alignment of your body.

You want to minimize lateral shifting of your torso, maintaining the alignment.

As with the one-inch bird dog, do 3 to 10 reps of 10-second holds on each side.

This is a great exercise that we learned from Gray Cook, although we use it with a different goal in mind. Whereas it's part of his balance-training repertoire, we use it to help develop a disassociation between pelvic/lumbar rotation and thoracic rotation. If you can't twist your shoulders and thoracic spine (middle back) while keeping your pelvis and lower back in a stable position, you'll be on the fast track to injury.

Grab a broomstick or dowel rod and get down on one knee, with your feet lined up as if you were on a tightrope. (We like to use a narrow board to ensure the proper alignment.) Keep your torso upright and hold the broomstick across the back of your shoulders.

If you struggle to get into this position, then this is the exercise you need to do. Work at it until you can hold for one minute on each knee.

If the position isn't particularly challenging, or it is initially but you work up to those one-minute holds, add a torso rotation. Your shoulders are the only part that moves; your pelvis, knees, and feet stay in the original position.

I recommend doing these exercises at the beginning of your workout, as part of your warm-up. We typically spent three to six minutes on them with the athletes we train, although we sometimes go up to 10 minutes. We find that's enough to accelerate recovery in our injured athletes while helping our pain-free athletes stay that way.

You should be able to do all these muscle-activation exercises without pain, or at least without provoking additional pain. In other words, nothing I've shown you here should make your current symptoms worse.

Make sure you breathe normally, and don't consciously draw in or brace your abdominals.

Finally, the exercises should be challenging, but not fatiguing. If your low-load system gets fatigued, the high-load system will take over, which is the opposite of our goals here. The key is that it's not the movement itself that matters, but how you respond to it. What's easy and non-fatiguing for one athlete might be difficult and fatiguing for another.

That's why we use a wide range of exercises, each of which has its own set of progressions.

I can't emphasize enough the importance of progression, but I use it here to mean the opposite of what you normally think of. Whereas you make strength gains by progressively increasing the load, you improve muscle activation by progressively removing load, and thus increasing the recruitment challenge.

Otherwise, you don't have to change anything you're doing right now. Keep lifting, and do your mobility drills and foam-roller work. Just make muscle-activation training part of your warm-up. It'll help alleviate any pain you have, help prevent pain you don't yet have, and enhance the effectiveness of everything else you're doing. Not bad for an investment of a few minutes a week!

- Warm Up Progression Vol. 1 Muscle Activation. Performance University, Nick Tumminello (2008).

- Diagnosis, Classification & Movement Solutions for Mechanical Lumbar Pain. Live Workshop by Mark Comerford. 1st International Lumbo-Pelvic Symposium. North East Seminars. Chicago, IL. Oct 2007.

- Understanding Movement and Function. Live Workshop by Mark Comerford. Kinetic Control. 2006.

- Hodges PW et al. Pain and motor control of the lumbopelvic region: effect and possible mechanisms. J Electromyograph Kinesiol. 2003 Aug;13(4):361-70.

- Moseley GL et al. Pain differs from non-painful attention-demanding or stressful tasks in its effect on postural control patterns of trunk muscles. Exp Brain Res. 2004 May;156(1):64-71.

- Tsao H et al. Immediate changes in feedforward postural adjustments following voluntary motor training. Exp Brain Res. 2007 Aug;181(4):537-46.

- Hodges PW. Changes in motor planning of feedforward postural responses of the trunk muscles in low back pain. Exp Brain Res. 2001 Nov;141(2):261-6.

- Hodges PW et al. Delayed postural contraction of transversus abdominis in low back pain associated with movement of the lower limb. J Spinal Disord. 1998 Feb;11(1):46-56.

- Hodges PW et al. Altered trunk muscle recruitment in people with low back pain with upper limb movement at different speeds. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999 Sep;80(9):1005-12.

- Moseley GL et al. Are the changes in postural control associated with low back pain caused by pain interference? Clin J Pain. 2005 Jul-Aug;21(4):323-9.

- Moseley GL et al. Pain differs from non-painful attention-demanding or stressful tasks in its effect on postural control patterns of trunk muscles. Exp Brain Res. 2004 May;156(1):64-71.

- Hodges PW et al. Experimental muscle pain changes feedforward postural responses of the trunk muscles. Exp Brain Res. 2003 Jul;151(2):262-71.

- Friden J et al. Mechanical considerations in the design of surgical reconstructive procedures. J Biomech. 2002 Aug;35(8):1039-45.