Gary Homann isn't your garden variety weightlifter. Sure, he's 180 pounds at 6% body fat. Sure, he had the best 500 meter indoor rowing time in the world last year in his class and he's been an ACSM certified health and fitness instructor for the past nine years. But Gary's also got a Master's degree in applied health psychology and is currently working on finishing his Ph.D. in psychology.

So why does T-Nation care what this guy has to say? Well, Gary's areas of specialization are maintenance of weight loss and long-term exercise adherence. In other words, this guy studies what keeps people like us training while many of our North American counterparts sit, uh, less than tight, on their couches.

Recently, Gary conducted a study examining the exercise habits and behaviors of nearly a thousand active people and discovered some very interesting things about what keeps them exercising once they start. So, whether you're looking for a way to make exercise a part of your long-term plan or whether you're hoping to help others do the same, listen up to what Gary has to say.

John Berardi: Gary, let's talk about the study you recently completed. Can you give us a brief synopsis and tell us what you were hoping to find?

Gary Homann: Well, my research focuses on the development of long-term exercise habits. Basically, what I'm trying to find out is how to keep people exercising once they start.

Interventions are getting better at motivating people to start exercising, but keeping them going is still a big problem. Half of people who start exercising quit within six months. (1) So if I get you to start exercising and check back on you six months later, I'll have just about equal odds of finding you at the gym or on the couch. This adherence problem is what I was hoping to address with my study. I think T-Nation readers will find the results very interesting.

JB: So tell us a little bit about the study. How many subjects, what type of subjects, etc.

Homann: Well, over a thousand people took the survey, but not everyone takes these things seriously. After throwing out the morons, inconsistent responders, and people who were limited in physical activity due to injury, illness, pregnancy, etc., I still ended up with 940 good surveys.

Of those 940 surveys, 64% of the responders were males and 36% were females. Also, to further define my subject population, thanks to you, JB, most of my survey participants were readers of your web site – many of which are also T-Nation readers. This means that my sample was highly skewed toward the more physically active end of the activity spectrum. This is great because I'm most interested in keeping people exercising, not motivating them to start.

JB: Let's talk turkey. I understand you were looking at relationships between body mass index (BMI), body weight, happiness with weight, hours exercising per week, exercise intensity, calories burned per week plus a whole lot more. Okay, quick question, were the participants savvy enough to give you a hard time about using BMI as a measure of body composition?

|

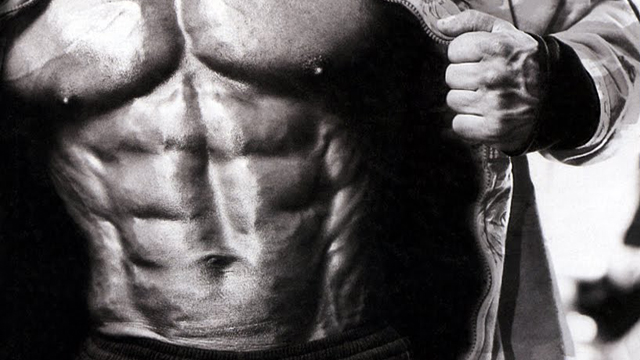

Homann: You bet they were. In fact, there were quite a few protests from readers about my use of BMI. It's true that BMI, or weight in kg/height in meters (2), is a miserable gauge of healthy body weight on an individual basis. And yes, people with a lot of muscle mass can have low body fat despite a fairly high BMI. I'm a good example of this. My BMI is over 25, which puts me in the overweight category even though my body fat is less than 6%.

JB: Me too. My body mass index is over 29 at 6% fat as well. It's even been as high as 34 back in my bodybuilding days.

Homann: But on the other hand, the BMI works pretty well when using large numbers of people – even with all those weightlifting types in my sample. Also, although I looked at the data in many ways, I looked at both BMI scores and "happiness with weight scores." This was simply another way to break up the subjects into sub-groups. This "happiness with weight" criterion helps pull the muscular types into the higher categories, even if their BMI is high.

Yet, as you can see in Figure 1, even with the muscular types there's a high negative correlation between BMI and happiness with weight. In most large population studies, the higher the BMI, the more unhappy someone is with their weight.

JB: Okay, got it. Makes sense. Now that we've described the subjects, it's time to talk data. Let's go over some of your findings.

|

Homann: In studying long-term exercise habits, I think it's important to consider what leads to the best outcomes. Once we figure out what's optimal, then we can figure out how to do it. So let's start by seeing how happiness with weight was related to the amount of time spent exercising per week.

Notice that people reporting less than four hours of exercise per week are likely to be somewhat unhappy with their weight and that people doing five or more hours of exercise per week tend to be fairly happy with their weight (Figure 2).

JB: Interesting, especially considering the current ACSM recommendations.

Homann: Indeed! The current government and ACSM (American College of Sports Medicine) recommendations call for 2.5 hours of exercise per week – an amount bound to leave people overweight and unhappy.

My survey agrees with Dr. John Jakicic's conclusion that while 2.5 hours of exercise a week can improve health outcomes, it's not enough to prevent weight gain. He recommends double that, or five hours, to optimize the impact of exercise on weight regulation. (2) Notice that in my study, five hours is the level of exercise where people become happy with their weight.

JB: But what type of exercise does this have to be?

|

Homann: More on that in a moment, JB. Before talking type (or intensity), let's look at the relationship between happiness with weight and estimated weekly calories from exercise (Figure 3). Once again the government/ACSM recommendations fall short. Following the minimum recommendation will accrue about 1500 calories per week. In contrast, National Weight Control Registry participants who maintained a weight loss of at least 30 pounds for five years burn about 3000 calories a week exercising. (3) Also, notice in Figure 3 that 1500 calories per week is associated with being slightly unhappy with weight, while 3000 is the threshold above which people tend to be happy with their weight.

JB: So, perhaps one reason why North Americas aren't getting in better shape is that we (i.e. the governing bodies) aren't telling them what it takes to get in shape.

Homann: That's exactly right. Interestingly, the government/ACSM exercise recommendations were lessened the last time they were changed. The logic goes something like this: "If we ask couch potatoes to do a lot exercise, they'll get discouraged and not do any. So let's ask them to do just a little bit and they might actually try to do it." Theoretically, getting the laziest people to be slightly active will have a bigger impact on public health than getting semi-active people to become optimally active.

JB: I never really thought of it that way before. Are there any data to suggest this line of reasoning is correct?

Homann: Well, first of all, I don't see how asking for less is going to get people to do more. It goes against common sense and all the theories I know. One of the basic principles of goal setting theory, for example, says that more challenging goals lead to higher performance.

In a recent study of weight loss on overweight people, researchers found that – surprise, surprise – when they prescribed more exercise, people did more exercise and had better long-term weight loss. (4) Second, I'm an individual, not a public health statistic. I'm interested in what's optimal for me, not what will save my HMO a few bucks. If I followed the minimum guidelines, I'd actually increase my risk of lifestyle diseases.

JB: So what's the bottom line? According to your study, what's the absolute minimum amount of exercise people should do if they want to improve their body composition?

Homann: If you want to be happy with your weight and keep from slowly getting fatter over the years, my research suggests shooting for at least five hours or 3000 calories a week of exercise. If you're nowhere near that, I'm not suggesting you meet that standard right away, but I am suggesting that you slowly work your way up to it within a few months.

JB: So what about exercise mode? Did some kinds of exercise fare better than others?

Homann: When someone asks me what the best kind of exercise is, I usually tell them "it's the kind you'll do." Having said that, I do think it's important for people to get at least some minimal amount – say an hour a week – of both aerobic and resistance exercise.

So if you're primarily a weightlifter or bodybuilder, it would still do your heart good to get 20 minutes of cardio three times a week. In the survey, people were 3.6 times more likely to be happy with their weight if they did at least an hour of each type of exercise. If they did a similar amount of exercise but all of one type or the other, they weren't as happy with their weight.

JB: Did you discover anything about specific types of exercise?

Homann: It's really hard to make that comparison, but I did compare high intensity sports like basketball, soccer and hockey to lower intensity ones like golf, softball and baseball. People who participated in the high intensity sports were both happier with their weight and had higher self efficacy, or confidence that they would continue to exercise.

JB: What else did your study say about intensity?

Homann: I specifically wanted to know how intensity of exercise is related to long-term weight control and long-term physical activity. Today's mainstream thinking has it that people are less likely to stick with higher intensity exercise. That's another reason for the government and ACSM lowering the bar on their exercise guidelines. I see the results of this lowered standard every day and I'm sure most of you have, too.

JB: You bet. Just the other day, my head strength coach in Toronto was complaining about some exercisers who refuse to do more than walk. He said, "JB, what the hell are these people thinking? The only way to lower the intensity of what they're doing is to sit down!" Heck, most people burn more calories per minute shopping than they do walking at the gym.

Homann: Yeah, I have to shake my head when I see healthy young coeds walking on the treadmill at the gym presumably thinking that is what's best for them.

JB: Me too. I shake my head. But if they're healthy, young and thin, for some reason I just keep watching. But I guess I shouldn't be saying that – some of my students could be reading this.

|

Homann: Take it easy, JB. Back to the intensity issue. Unfortunately, this is another example of experts prescribing what they think people will do rather than what's best or optimal. Reviewing the research makes it clear that higher intensity exercise leads to a longer life and less cardiovascular disease. (5) Studies have also demonstrated that people who do higher intensity exercise are leaner than people who only do low or moderate intensity exercise – even when they eat more calories and burn fewer calories during exercise. (6) In short, you get more bang for the buck with higher intensity exercise.

JB: True, but I'd caution readers not take this to the extreme and get themselves into overtraining trouble.

Homann: You're right. Keep in mind, high intensity for a T-Nation reader is pretty much off the charts for the average exerciser.

But let's go ahead and look at what the study suggests. Notice in Figure 4 that the proportion of medium intensity exercise stays fairly stable across different levels of happiness (40-50%). Most of the differences are in high and low intensity exercise. Generally speaking, people who are happier with their weight do more high intensity exercise and people who are unhappy with their weight do relatively more low intensity exercise. Although you can't see it on this graph, people unhappy with their weight actually reported more minutes of low intensity exercise than happy people.

JB: So what about the intensity vs. adherence question?

Homann: From my survey data, I can't directly say whether beginning exercisers who start incorporating higher intensity exercise are more or less likely to quit. What I can say, however, is that people who've been exercising longer do more high intensity exercise both in proportion of exercise and in total volume.

Realistically, I think the smart thing to do for a beginning exerciser is to incorporate high intensity exercise slowly over the course of several months. On the one hand, too much too soon leads to extreme soreness and injuries, two of the biggest reasons for a return to the couch. On the other hand, doing the same routine without ever pushing the envelope leads to a plateau in improvement, which is another major reason for quitting.

JB: So how do exercisers avoid the two big pitfalls that lead to quitting – too much pain at the beginning and not enough results later on?

Homann: I suggest a periodization plan for new or returning exercisers from the very beginning.

JB: But many exercisers think periodization is only for advanced athletes.

Homann: I know but it's probably just as critical for beginners. In addition to lessening the chance of injuries and extending improvements, a periodization plan sets up longer-term expectations and goals. Another very important aspect is that the exerciser can see upcoming weeks when the load will be lighter and even a week off once in a while.

JB: Interesting stuff, but much of this is pretty much old hat for most here at T-Nation.

Homann: You're right. Much of what I've discussed already is old hat for most in the fitness and exercise community. However, sometimes it takes the research world a little while to catch up. Hang with me though because I'd like to address a few newer things that some of the readers might not realize.

The primary purpose of my survey was to answer the following question: What characteristics or strategies distinguish beginning exercisers from those who have maintained an exercise habit? Or, put a different way: What can you do to stay off the couch?

Based on previous psychological theories and a few wild ideas I had of my own, I tested 22 characteristics or strategies I thought might work. In order to best analyze the survey data, I categorized the 940 participants into one of seven exercise stages:

1. Pre-contemplation: Not currently a regular exerciser and no plans to start

2. Contemplation: Not currently a regular exerciser but thinking about starting

3. Preparation: Planning to start exercising regularly within the next month

4. Action: Regular exercise but for less than 6 months

5. Maintenance: Regular exercise for at least 6 months but less than 5 years

6. Transformed: Regular exercise for at least 5 years but not always active

7. Always Exercised: Lifelong regular exerciser

Of the 22 strategies I tested, a few just didn't seem to have any impact on exercise adherence. However, most were significantly different between at least two consecutive stages of the seven above.

JB: So which of the 22 strategies seem most important from an exercise adherence perspective?

Homann: Since the focus of this paper is to discover ways to keep people exercising once they've started, I'll like to share four strategies that were significantly different between new exercisers (Action) and those who have been exercising for at least six months (Maintenance).

The first strategy is self-monitoring, which is simply recording or keeping track of what you do. A workout log is one example. Several studies have demonstrated beneficial effects of self-monitoring on exercise behavior. (7, 8) For whatever reason, the simple act of writing it down helps people do more exercise and keep doing it. One might think self-monitoring wouldn't be necessary after exercise has become habitual, but the survey indicates that people continue to self-monitor, even the individuals in the "always exercised" group.

It appears that beginning exercisers endorsed less than half of the self-monitoring questions, but those who've been at it for over six months endorsed about two-thirds.

The reason self-monitoring is so useful is that it can serve as a reminder when you're slacking and it can help you spontaneously set goals. For example, my wife keeps a chart that's basically a bunch of check boxes. Each calendar day has a box for cardio, legs, arms, abs, etc. It works for her because she can see at a glance how long it's been since she did a particular type of exercise.

JB: So the message for amateur and veteran exercisers alike is to keep some sort of training. Gotcha. What next?

|

Homann: Set goals.

Goal setting is a major component of many exercise programs and for good reason – it works. It's probably no surprise that setting exercise goals helps beginning exercisers make the habit stick, but does exercise become such a habit at some point that people no longer set goals?

A look at the goal setting graph (Figure 6) suggests that the answer is probably "no." Goal setting actually continues to increase the longer a person has been exercising. Goal setting appears to be a useful strategy for beginning exercisers and one that tends to increase over time. There's actually a huge body of literature on how to set goals. The most effective goals are specific, challenging but attainable, and have both short and long-term targets. (9) If you're a beginning exerciser, learn how to properly set goals – it works.

|

JB: I think it's critical for readers to understand, though, that goal setting is both art and science. Most simply think that they need to pick a goal and go for it. While this certainly stimulates some action, I try to teach my clients not only to set realistic, measurable goals but also to understand the appropriate time frames necessary for the accomplishment of these goals. Without understanding how to set goals properly, a trainee can get even more frustrated than if he had no goals at all!

Homann: Good point. In addition to goal setting, here's another useful strategy: program variety. Systematically varying an exercise program (periodization) provides numerous physiological benefits and is done by nearly all high level athletes. One study also found that it may be more enjoyable and lead to better adherence in beginning exercisers. (10) Not surprisingly, participants in that study who were instructed to change their exercise mode every two weeks adhered to the program better and enjoyed it more than those who were asked to do the same type of exercise for eight weeks.

JB: Not surprising, is it?

Homann: No, but what was surprising was that the prescribed variability group did better than a third group in which the participants could vary their exercise mode at any time.

JB: So planned periodization is better than what's been called "instinctual training" whereby trainees just train whatever they feel like, whenever they feel like it.

|

Homann: It appears so, at least from an adherence perspective.

Now back to the variety issue. In my survey, the longer a person had been exercising, the more program variety questions they endorsed (Figure 7). I was a little surprised that variety continued to increase even after five years of regular exercise (between maintenance and transformed stages), but that's what people reported. In any case, it appears that if you're starting an exercise program, changing up your workouts on occasion is a good idea and planning your variety in advance may be even better.

JB: It's cool to know that periodization has both physiological and psychological benefits, improving both results and adherence. What about that last strategy?

Homann: In addition to keeping a workout log, setting appropriate goals, and periodizing your workouts, getting active in an exercise community seems to be important as well.

The final strategy for improving adherence is something I call exercise community involvement (ECI). ECI is the extent to which a person is involved with people, activities, contests and events tied to their exercise activities. This strategy is one of my wild ideas that happened to work out nicely. (Notice I didn't reveal the other crazy ideas that didn't pan out.)

I hypothesized that people who engage in physical activity solely for the purpose of exercise wouldn't be as likely to continue as people who get more involved. By involvement, I mean things like joining a church league basketball team, training for the upcoming mini-marathon, taking a karate class or better yet, entering a few karate tournaments. Higher involvement should lead to greater intrinsic motivation for the activity, a circle of friends involved in the same activity and in many cases, not thinking of the activity as exercise but "playing" a sport.

So, what did the survey say? Figure 8 shows a huge jump between the beginning exercisers in action and the maintainers who've been exercising regularly for at least six months. That was certainly supportive of the idea of ECI, but when I fiddled with the data I found a rare "hey honey, check this out" stat.

JB: What's that?

Homann: Every person in the survey who said they participate in exercise events also said they were highly confident in continued exercise – not a single exception in a sample of nearly 1000 people! If you really want to make your commitment to exercise stick this time, I'd suggest picking out a sport or activity you think looks cool and really getting involved with it. Chances are you'll not only stick to it, but you'll have a heck of a lot more fun learning skills and making friends than you would puffing on a treadmill with your Walkman on a few times a week.

JB: I'd imagine being a member of T-Nation also offers ECI points, no?

Homann: Lots of them. Actually, long-term exercisers in the survey said they read more articles on exercise than neophytes, so it really does in a way.

JB: Hey Gary, this has been a really fascinating interview. Thanks for taking the time to do it! Got any remaining tips and tricks that can help our readers increase exercise motivation, adherence or inspire others to do the same?

Homann: Sure. The techniques I talked about today – self-monitoring, goal setting, programmed variety, and exercise community involvement – are all things a person can do to help him become a lifelong exerciser. But external techniques only help a person make the most important change, which is on the inside. The real goal is to get to the point where exercise is just part of who you are.

JB: Good advice! Thanks again for the chat!

References

1. Buckworth, J., & Dishman, R. K. (2002). Exercise Psychology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

2. Jakicic, J. M. (2003). Exercise in the treatment of obesity. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, 32(4), 967-980.

3. Klem, M. L., Wing, R. R., McGuire, M. T., Seagle, H. M., & Hill, J. O. (1997). A descriptive study of individuals successful at long-term maintenance of substantial weight loss. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 66, 239-246.

4. Jeffery, R. W., Wing, R. R., Sherwood, N. E., & Tate, D. F. (2003). Physical activity and weight loss: Does prescribing higher physical activity goals improve outcome? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 78(4), 684-689.

5. Erlichman, J., Kerbey, A. L., & James, W. P. T. (2002). Physical activity and its impact on health outcomes. Paper 1: The impact of physical activity on cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: An historical perspective. Obesity Reviews, 3, 257-271.

6. Yoshioka, M., Doucet, E., St-Pierre, S., Almeras, N., Richard, D., Labrie, A., et al. (2001). Impact of high-intensity exercise on energy expenditure, lipid oxidation and body fatness. International Journal of Obesity, 25, 332-339.

7. Weber, J., & Wertheim, E. H. (1989). Relationships of self-monitoring, special attention, body fat percent, and self-motivation to attendance at a community gymnasium. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 11, 105-114.

8. Noland, M. P. (1989). The effects of self-monitoring and reinforcement on exercise adherence. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 60(3), 216-224.

9. Annesi, J. J. (2002). Goal-Setting Protocol in Adherence to Exercise by Italian Adults. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 94, 453-458.

10. Glaros, N. M., & Janelle, C. M. (2001). Varying the mode of cardiovascular exercise to increase adherence. Journal of Sport Behavior, 24(1), 42-62.