In the last installment in this series, I wrapped up the time I spent training at Westside Barbell under strength coach/genius Louie Simmons. Although all good things must end, I'm very proud of what I accomplished there both as a lifter and as part of the Westside team.

I speak so highly of Louie that people often ask why I ever left Westside. They assume it's because I developed something "better" or that I wanted to put my own "stamp" on Louie's training.

Other stories include us having a massive argument and Louie kicking me out of his gym, even a supposed fistfight. I'm waiting for the version where we're duking it out in a windy elevator shaft and he cuts my hand off before telling me that he's my father.

The truth is, I left because I was done.

2003

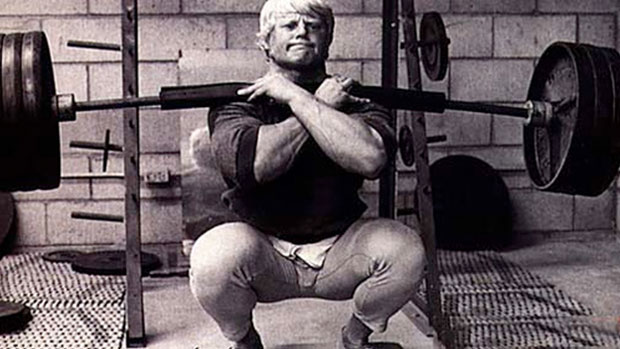

It was 2003, and I'd been powerlifting for 20 straight years. I was beat to hell. Although most of my injuries occurred before I set foot in Westside, the writing was already on the wall – and regularly putting 800 pounds on my back certainly wasn't helping things.

I'm going to switch gears for a moment to call some of you young guys out. I hear constantly from powerlifters claiming their bodies are "trashed" or their backs are "fucked" – and when I ask for more details, it's often stuff that any lifter at Westside trains with every day.

Some of you guys need a serious reality check. Here's what I was like in 2003.

Groin

I injured my groin on both sides. It sucked, but I just wrapped it up and dealt with it.

Abdominals

I tore my lower abdominal muscles while squatting. It was perhaps the most painful injury I'd ever had. I also strained both intercostals, twice.

Spine

The following discs are herniated: L4, L5, C4, C5.

Calves

Both torn. Huge indents in each. Looks freaky though.

Knees

Strained the right ACL at least three times, probably more.

Hamstrings

The right's a mess. Tore it so bad it almost needed surgery.

Quads

Pulled the right quad in the early 90's. It was so bad it turned my entire leg black.

Pecs

I've torn both sides at least 20 times, and each tear caused the entire pec to turn black and blue. I also tore the left pec at the tendon and needed surgery to fix it, and tore the right pec in half but opted to skip the surgery.

Shoulders

In the right shoulder I had a torn supraspinatus, bone spurs, and now, arthritis. I had this shoulder cleaned up with the AC shaved down to allow more movement but to no avail. A total replacement is the only option left and this was another big reason for my retirement.

Working around or through the other injuries was a pain in the ass, but at least it was doable. Total replacement of my shoulder was certainly an option, but their longevity is based on usage and time. Considering I was at Westside, I knew I'd likely need a new one within 2-3 years – if it lasted that long.

Granted, there were guys who were way more beat up than me who were still lifting and going for it, but by '03 I'd crossed "the line."

The Want It Line

To be a successful powerlifter, you have to be fearless and want it more than anything else. You can never be scared to lift a weight. One of three things will happen: you get the lift, you miss the lift, or you get hurt. I'd accepted that years ago and it served me well, but obviously broke me down.

Suddenly other priorities, namely work and family, were becoming more important. And I was beat to shit and needed a new shoulder. It was draining the want out of me.

When I started asking the surgeons, "Do we really need to do this now?" instead of, "How long will this take to get back?" I knew for sure I was done.

Not "That" Guy

I also left Westside because I wasn't ready to start coaching others. Not because I don't love coaching – I do – and some questioned why I didn't stick around and assume a mentoring role.

It was too soon for me. I was still a lifter, not a coach. Even today, I'm still a lifter first – sure, I'll help others, but it has to be on my terms. If they ask for a program, then they better do what I write or I'm done with them. If they ask for advice and then question it, I won't offer advice again.

(To this day I'm amazed how after being in this sport for close to 30 years that someone with one year of "internet research" will ask a question only to refute whatever answer I give. If they knew better then why the fuck did they ask? To waste my time?)

I was also starting a new business. Training with the morning crew meant I wasn't showing up to work until 1 PM – meaning that I was a part-time employee at my own business. My apologies to the 4 Hour Workweek crowd, but anyone who's ever started up their own company knows that it takes a hell of a lot more time than that.

Still, the biggest reason was I didn't want to be "that guy." Hanging around and offering wisdom and encouragement and maybe jumping in for the odd workout might've been fun, but it would've also reminded the young guys of what they could become. I would've been a liability, not an asset.

Remember, Westside Barbell isn't a "gym," but a team of lifters striving to be the best of the best. When you're no longer capable or don't have the will to be that anymore, it's time to leave to make room for the next generation to kick the shit out of your lifts and records.

It was my time and I have no regrets. My decision is reaffirmed every time I see another Westside lifter break a world record.

Training The Jersey Shore Way

So now I'm training at my own gym at EliteFTS. It's well equipped of course, and I'm doing what I can, but everything still hurts. My shoulders are like a bad joke, and now even my feet hurt. I have no idea why.

It was around that time that I'd arranged a meeting with some popular strength coaches and facility owners to discuss their equipment needs. The arrangement was to meet in New Jersey, on the Jersey Shore, and on the guest list was Joe DeFranco, Alwyn Cosgrove, Jason Ferruggia, and Jim Wendler.

I'm not even sure where to begin with this one. I've been to many beaches and beach houses so I assumed this place would be no different. Man, was I wrong.

The first night we walked down the street to some club and the place was packed full of Under Armor wearing guys with gold chains, big arms, and ILS (imaginary lat syndrome). And I'm not talking about just a few guys – it was almost everyone.

After spending 40 minutes making our way to the back porch of the club, I told the guys that we needed to get the fuck out of there – but there was no way I was going to fight that crowd again for another 40 minutes to get to the front door.

We spotted a back way out and made our way over, until some ILS Guido bouncer sporting the biggest gold chain I'd ever seen stopped us. It looked like something you'd attach to a barbell and do pulls with.

He said we weren't allowed to walk down the seven steps out to the beach that would take us back to the street. Being a former bouncer, I tried to play this off polite and cool and was even making progress until one of the guys said he was going to back kick the fucker in the head.

At this point I figured we'd end up in a fight and get tossed in jail, or at the very least I'd wind up pulling something or screwing up my shoulder even worse.

We decided to walk back to the front door, only this time it didn't take as long as we wound up getting an escort by Gold Chain Guido the Bouncer. I still have no idea why he didn't escort us out the short, seven-step back way. It would've taken a fraction of the time.

After we got out, I suddenly realized that Wendler was nowhere to be found. I know Jim well, too well, and there was no way in hell he was still in there. If he was and we weren't with him, there was likely going to be a way bigger problem than just me pulling something. I called him on the cellphone to see where he was.

"Dude," he said, "I looked in the front door, turned around, got some ice cream and went back to the house. I'm lying on the couch. What are you guys doing?" Ten minutes later we were there with him.

The Braveheart Assessment

After the next day's meeting, we left the condo to grab dinner. Walking down the steps to the restaurant, everybody zips by me while I do my usual stair routine: Left foot to step. Right foot meets left. Left foot to next step. Right foot meets left. I don't alternate steps like a normal human because my body doesn't work that way anymore.

Cosgrove sees me in action and can't believe it. "Dave, what the hell is the matter with you?" he yells in that freak-show Braveheart accent of his.

Once Cosgrove realized that this wasn't an act, he quit laughing. He then says he's going to put me through a movement assessment as soon as we get back to the condo.

The first thing I was to do was put my arms over my head and squat down into a full squat. Sure thing Alwyn, except I can't even raise my arms over my head.

Fail. Next test.

He then told me to lie on the floor and reach my arms back. Well, when you're 290 pounds you don't just "lie" on the floor – you have a couch or chair nearby, and you ease yourself down into a half-kneel, then a full kneel, then maybe you roll to the ground.

Fail. Next test.

It was supposed to be a 12-test assessment and Cosgrove tried to run another test or two but stopped halfway. He'd seen all he needed to determine that I had the worst mobility of anyone he'd ever seen.

Back to the Living

After that humiliating experience, I knew that if I was to ever lead a normal life again, much less train normally, I would have to suck it up and take the steps to get my mobility back.

First, I consulted the writings of the mobility experts like Cosgrove, Cressey, and Robertson. I made a few calls, watched some DVDs, and asked for some sample mobility routines.

In the end, I put together this monster. Each exercise I did for 1 or 2 sets of 10-15 reps.

- T-spine mobility

- Ankle mobility

- Bird dogs

- Camel – cats

- Leg swings to the side

- Leg swings to the front/rear

- Static lunges

- Lateral squats

- Wall slides

- Scap push-ups

- YTWLs

There were about 10 other drills that I've since blocked from my memory.

The whole thing took me about 25 minutes to complete and I did it before my usual powerlifting workout of heavy benches, safety bar squats, etc. I did this for close to six months, fairly religiously.

It frickin' sucked.

First, it was boring as hell. If you enjoy doing YTWLs with a four-pound dumbbell, then you've probably never felt what benching 500 pounds is like.

Second, it drained all of my mental energy for the real workout. After 20 minutes of flopping around like a retard from band camp, I lost all my jam for getting under the heavy bar and tearing shit up.

Finally, as much as it "warmed up my stabilizers," I found it gassed my smaller muscles more than anything. Doing benches after a bunch of YTWLs are supposed to make benches less painful, except for me. The pain was far worse. Great.

So I scrapped it. In my usual blast and dust fashion, I scrapped everything. I took a month off completely.

The New Plan

The time away from lifting did me more good than any mobility work. Not only because I needed the break – I did – but the fact was, mobility training wasn't working. I was getting progressively weaker. I was down below 70% of what I once was.

Worse still, I was haunted by my old PRs. I was starting to hear, "What's the point?" creep into my head, which is a scary thought for a guy who just retired from anything.

I started to reflect on my training and when things last felt really good, back before it all started to go off the rails.

I decided to go back to bodybuilding training – but with a twist.

The New Rules of Bodybuilding

Here's the deal. Powerlifting is about finding the shortest range of motion possible.

Look at the bench press. If your setup and arch is sound, it's a very short (albeit very safe) range of motion.

Bodybuilding, in the purest sense, is the opposite. The most effective movements generally take the muscles through the longest range of motion.

I realized that I hadn't done any full range of motion work for years, and if I were to regain my "functional mobility" this would be where to start.

I first established some rules:

- I would not use any movement that I'd performed in the last 10 years. I wanted no frame of reference, no reminder of what I was once capable of.

- I'd perform every repetition slow and controlled, both eccentric and concentric.

- All exercises must take the muscle through the fullest range of motion.

As for my 20-minute dynamic warm-up? It was out the window. My warm-up was now a few arm or leg swings and onto the first exercise, except with a ton of warm up sets.

I structured a four-day a week workout that was painfully basic:

- Monday: Chest, shoulders

- Tuesday: Legs, abs

- Thursday: Back

- Saturday: Arms

The exercise choices were as follows:

- Chest: Machine presses, machine flyes

- Shoulders: Cable lateral raises (keep in mind I can't raise my arms above my head), reverse pec deck

- Back: Lat pulldowns, dumbbell rows, chest-supported rows

- Triceps: Rope extensions on incline bench, machine extensions

- Biceps: Cable curls, full range dumbbell curls, lying cable curls

- Abs: Ab mat, Swiss ball crunches

- Hamstrings: Romanian deadlifts, glute ham raises

- Quads: This was a toughie. Since I couldn't squat and it was tough to find moves where I got a real stretch, I just doubled the amount of hamstring work I did.

I selected movements based on what would work the specific muscle through the greatest rang of motion. In the case of my shoulders, I wanted to basically turn them off when I was training chest. Hence, the one-dimensional movements; it allowed total focus on the target muscle.

I did two or three of the above per muscle group. Each exercise was performed for 2-3 sets of 10-15 reps.

Weights were subordinate to my larger goal, which was to nail the rep speed and range of motion and not pull anything in the process. So it had to be light, yet still heavy enough to allow me to stretch and flex very hard. Each of these positions was held for a 1-2 count.

Since weight wasn't a priority, most of the weights I used were very low. I remember getting my ass kicked by 40-pound dumbbell rows and 90-pound lat pulldowns.

So how did it work?

Within one month, I felt like a million bucks. Virtually everything quit hurting, and my body took on a completely different look. I looked more "jacked." My vascularity had improved, and my muscles were much rounder and fuller. Most importantly, except for the shoulder that still needed replacement, all the other issues were gone!

I was hooked.

What Did I Learn?

I followed this setup for about a year, changing exercises every three weeks but always to moves that were completely new to me. That was crucial. It kept my ego out of the equation and kept me focused on the task at hand.

As a bonus, over the course of that year I was able to say something I'd never been able to say since my first day of training: I never once suffered an injury.

If that fails to impress you, keep in mind the kind of lifter I was (am). Refer to the above list of injuries. Now consider this: I never missed a meet due to injury. Ever.

If I blew something out I'd miss a workout, maybe two. I'd never miss a whole week and I'd never, ever miss a meet.

That was just how I was back then. If I popped a disc on Monday, I might hobble around and take it easy for a day or two – but I found a way to squat Friday. It might mean wearing two weight belts and wrapping a band around my head, but I squatted.

I developed a reputation for getting guys into meets, despite what their doctors said. No matter what the injury was, I knew what they needed to do because I've been through almost everything.

In hindsight, I was reckless, stupid, and likely did more harm than good, but my track record stands. If you were hurt but still wanted to lift, go talk to Dave.

I could write stories about how to perform with pec tears, hamstring pulls, back issues, knee pain, and many other injuries, but there will always be someone who will take what I say as an endorsement and in two months the sheriff shows up at my door with a court order. Some things are better left in the gym and the warm-up room.

I always rushed recovery. I pushed the envelope so many different ways it's a wonder I could even pull off that fucked up walk Cosgrove was ribbing me about.

That isn't to boast or sound cool – it's really sad. If I had done the opposite and extended my rests by even two weeks here, two weeks there, I could still be powerlifting competitively today.

What Would I Change?

This is one of those rare occasions where I wouldn't change a thing. This form of true "functional training" completely saved me.

I would've perhaps kept some of the mobility drills, as I do see value in them. I would just do maybe five minutes worth, not 25 minutes like I had been doing.

As a big, tight, fucked up ball of muscle, rolling around on the Swiss ball was a waste of time. I needed something more aggressive to force my range of motion. A heavy chest supported row that forced my lats through a full range of motion did more than all the goofy drills combined.

But the biggest change I'd make, even going back to my powerlifting days, would be to throw in a couple sets per body part of these slow tempo, full range of motion exercises.

The power lifts shorten the functional range of motion, and if steps aren't taken to reverse this, problems like I had occur.

The key is to choose lifts where you don't know how strong you are, so you don't rush it. The more banged up or tight you are, the more lifts you should throw in.

Also, don't use lifts where you develop compensatory acceleration. Remember, this is the opposite of powerlifting – you want to isolate the target muscle as much as possible.

For my chest, bench presses would never work as my triceps immediately take over. For me to isolate and stretch my pecs, the machine press was ideal. The fact that there's no stabilizer activity was a benefit – I wanted to focus on just my pecs firing. This is an instance of machines being the right tool in the toolbox.

Static stretching helps, and there are plenty of fat but flexible powerlifters, but there's something about loaded full ROM exercises that's much more effective.

Perhaps it's because it's not just a passive movement (a stretch) but also an active one (exercising under resistance through a full range of motion). I can only comment on what I experienced – a year of this saved both my lifting and my mobility.

Here's an analogy. An athlete is like a racecar. Every part of the car has to be in working order to run properly. If you run it hard for years and don't do the necessary maintenance, it's eventually going to either break down or perform sub-optimally.

Adopting this training style was like taking a racecar apart and cleaning each piece one at a time, making sure they worked independently. Only when I was satisfied with each part's individual performance would it go back on the car.

The Recipe

So here's the recipe if you're a tight bastard and fairly screwed up:

- Warm up with a few basic mobility drills. Arm circles, swings, pull-aparts, etc. Spend less than 5 minutes on it – you don't want to pre-fatigue anything.

- If you're just kind of tight: Progressively warm up for your first key lift. Take 6, 7, even 10 sets to get to your work weight. Charge up your nervous system and pump as much blood into the muscle as possible.

- Bust your ass as normal.

Then, after your regular training:

- Do 1-2 extreme range exercises per screwed up bodypart.

- Start at 2-3 sets of 10-15 reps.

- Do the movement slow. Slow up, and slow down.

- Go for full, excessive stretches and peak contractions. If you do this faithfully, the weight will be light. If you find yourself piling on the plates, recheck your form. Don't load these moves. You'll screw it up.

- Expect some weird soreness, even some discomfort. High reps and slow tempos through ranges you're not used to training isn't fun.

- After your workout: Do some specific mobility drills (external rotators, trap raises, etc.). The idea is to hit these little muscles after your big work is done, not before. Why fuck up the most important part of your workout by pre-fatiguing those muscles?

If you're a real mess:

- Warm up with a few basic mobility drills. Arm circles, swings, pull-aparts, etc. Spend less than 5 minutes on it – you don't want to pre-fatigue anything.

- Skip the initial regular lift. You're too far-gone. Just bite the bullet and do more extreme full range work. You won't regret it. The heavy weights will still be there in a month or two.

- Do 2-3 extreme range exercises per screwed up bodypart.

- Start at 2-3 sets of 10-15.

- Do the movement slow. Slow up, and slow down.

- Go for full, excessive stretches and peak contractions. All the above shit.

- After your workout: Do some specific mobility drills.

Wrap Up

This might sound as boring as hell – and at times it was – but it also completely rejuvenated both my love of lifting and my life. If you're finding just getting your body to move like it once did a chore, you need to take a serious look at your training and see how some intelligent mobility work could benefit you.

It brought me back from the brink. Why can't it help you?

In the next installment, I'll talk about what my fat 290-pound ass went through working with a friendly SOB named John Berardi.