Tight hamstrings are the bane of every athlete's existence, paving the road to an assortment of pains and problems ranging from muscle strains, knee pain, and bad posture to decreased strength and performance.

Maybe this is why hamstring stretching is such a ubiquitous feature in fitness programs, pre-sport warm-up, and physical therapy protocols.

Despite countless hours spent stretching and massaging these musculoskeletal incorrigibles, most people still struggle with tight hamstrings. But it's not for the reason they think.

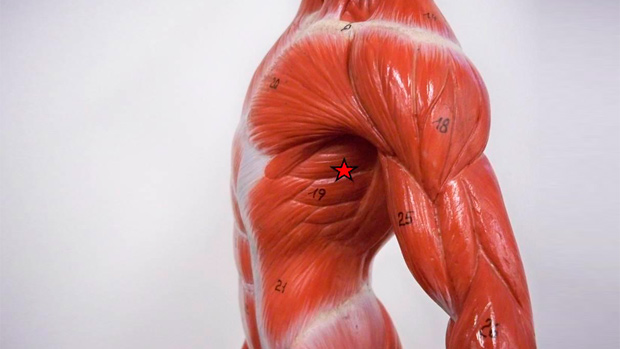

Muscles aren't solid hunks of flesh that function as a singular entity. Like all of our various body parts, muscles are made up of increasingly smaller subunits that string together like links in a chain.

Within each subunit are proteins, which have the unique ability to move closer (contract) or farther away from each other (stretch). The relative proximity of the proteins to each other dictates the overall length of the muscle.

Conventional thinking is that if a muscle lacks range of motion, it's because the chain is too short – not enough links – or the links have somehow knotted-up. In theory, stretching would fix the tightness by pulling the links apart or, over time, causing more links to be added to the chain.

The reality is that outside of extremely rare circumstances (usually involving long-term immobilization after an injury), muscles don't drop links from the chain. Muscle length, in the absolute sense, is always the same.

What CAN change is the amount of tension in the muscle, and this is a function of the overall position the muscle is in, rather than a change in raw materials. So, while your hamstrings might be "tight," it's probably not because they're too short.

Your hamstrings, and all your other muscles, are like giant elastic bands. When you pull the ends of these "bands" in opposite directions, they get longer and tighter. In other words, the more they're stretched, the more tension gets stored in the bands and the more resistant they are to further stretch.

That's why decreased mobility and that feeling of "tightness" behind the knees when you bend forward doesn't necessarily mean that the muscle is short; it's often instead a sign that the opposite is true.

This explains why some people's tight hamstrings never seem to improve, no matter how much they stretch them. The truth is, most people are in the too-long camp, rather than the too-short camp.

Blame it on the pelvis.

In addition to being the anchor point of your hamstrings, the pelvis also must synchronize its position with your rib cage. The thoracic diaphragm (attached to the inside of your rib cage) and the pelvic floor (muscles that sling across the pelvis floor) act as a container of sorts for the internal pressures created by both air flowing in and out of your lungs and internal organs shifting around during movement.

It's kind of a gross physics peculiarity that your musculoskeletal system has to deal with, but your pelvis and the muscles of the pelvic floor set the foundation for the rib cage and thoracic diaphragm to act upon. Between the thoracic ceiling and the pelvic floor is all your squishy stuff.

None of this is a problem. Until it is.

Modern humans do a lot of sitting and a lot of stressing out, both of which have an effect on the body. Long bouts of sitting put your hip flexors in a shortened positioned. This eventually pulls the pelvis forward and down in the front while pulling it up in the back where the hamstrings attach. This results in pulling one end of the muscles away from the other end.

As far as stress, let's just say that it has the expected effect on our physiology, including increased heart rate and blood pressure, additional perspiration, and dilated pupils, along with a host of other markers.

One of these markers is increased extensor tone (hyperactivity) in the muscles that extend the body, especially in the back. Essentially, it's a fight-or-flight position that prepares the body for action.

This is the same situation we find ourselves in when we do virtually every major lift – squat, deadlift, pull-up, and press – for two reasons. First, lifting very heavy shit is extremely stressful and threatening to your body, and second, because extension is a very stable position from which to do that.

Just as before, this puts the pelvis in a forward, anteriorly rotated position, pulling the hamstrings long and taut like overstretched elastic bands. In either case, the net results are over-lengthened hamstrings with excess tension.

Other than providing some transient increase in range of motion, stretching won't work here. Your focus needs to be on reestablishing a normal position for your pelvis, which, in turn, will restore normal length and tension to your hamstrings.

Here are four exercises you can do for 5-10 minutes a day that will make your yoga mat obsolete.

1. 90/90 Skywalker

If long, over-stretched hamstrings, secondary to a forwardly rotated pelvis, are the problem, then restoring normal position is a game of balancing tension. Put enough pressure on a bone and it'll shift position. This is the concept behind using braces to strengthen your teeth.

The 90/90 Skywalker (credit to the Postural Restoration Institute for the idea) uses tension produced by the hamstrings and its attachment points on the pelvic bones to pull the pelvis back and down:

- Put your feet on wall, chair, or couch.

- Press down through your heels, imagining that you're pulling or dragging the wall (or whatever) toward the ground. This should engage the back of your legs, like a hamstring curl without any movement.

- Curl your butt under, aiming to bring the back pockets of your pants to the back of your knees.

- Take one foot off of the wall and reach it towards the sky.

- Reach your opposite arm toward the foot of the leg that's in the air.

- Maintain that position for 3-5 sets of 5 breaths, reaching a little farther each time you exhale.

2. Lazy Bear

Hamstrings aren't the only muscles that hold sway over the position of your pelvis and enable you to touch your toes. That's where your abs, specifically the internal obliques, come in.

These powerful abdominal muscles, situated on the sides of your torso, connect your rib cage and pelvis. This makes them well positioned to change the shape of the spine while taking the arch out of the middle and lower portions, thus rotating your pelvis backward.

- Start in an "all fours" position – hands and knees on the ground, with your feet flat against a wall.

- Slide most of your weight forward toward your arms as you roll your pelvis back and round your upper back, spreading your shoulder blades apart and pulling your rib cage in toward your body.

- Lift your knees 1-2 inches off the ground.

- Exhale and try to get deeper into this position.

- Inhale and try not to lose the position.

- Repeat for 3-5 sets of 5 breaths.

3. Tall Kneeling Band Reach

If the lazy bear is Hamstrings-Abdominal Integration 101, this move is the 102 version, using an upright position, but with knees still flexed for optimal recruitment and an added reach to align the position of the rib cage and the pelvis:

- Kneel with both knees on a mat or the ground. You can place a weight plate on your heels or tuck your feet under a glute-ham pad.

- Push your knees down and pull your hips into a posterior tilt.

- With a band wrapped around your upper back for resistance, exhale and reach your arms forward, pulling your ribs down and back.

- Repeat for 2-5 sets of 5 breaths.

4. Rear Leg Elevated RDL

One problem associated with an anteriorly-oriented pelvis is an inability to expand the backside of the hip during forward bending. As a result, the femur can't fully push backward into the socket to allow for normal hip rotation to occur.

Rather than trying to stretch the problem away, here's how to use a modified traditional single-leg deadlift to fix it instead:

- Place a weight plate under the back foot (this will position the femur toward the back of the hip) while holding a weight in the opposite hand.

- Rotate your hips toward the back foot as you reach with the weight in the same direction.

- Push into the ground with your forward leg to maximize the posterior hip shift.

Tight hamstrings are often a problem, but stretching is rarely an effective cure.

That's why people can stretch every day for years without ever making meaningful or lasting changes to their range-of-motion or subjective feelings of tightness in the backs of their legs.

More often than not, the real problem is over-stretched tissue, leading to excessive length tension.