Fitness certifications are like personality disorders: just about everyone in the business has at least a couple. Take me, for example. Even though I don't train clients for a living, I've accumulated my share: Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist, Poliquin Level 1, Certified Sports Nutrition Advisor, an Olympic weightlifting credential, and a few others I've either forgotten about or decided to block from memory.

Most of us in the fitness industry appreciate, to one degree or another, what Alwyn Cosgrove said in this interview: "All certifications show is basic competence that you won't hurt someone. It doesn't make you an expert. It just shows that you're not an idiot."

So, long story short, my quest for basic competence and non-idiocy has given me an appreciation of what can and can't be achieved with official certifications. I can pass the comprehensive and challenging test to get my CSCS, for example, but that doesn't mean I'm qualified to take over a college strength and conditioning program. And I remain a piss-poor Olympic lifter, despite the fact I've earned a piece of paper certifying that I know how to do cleans, snatches, and jerks.

A cynic could assert, with little argument from industry insiders, that many credentials only exist as a way for the certifying individual or organization to make money off his or its reputation and status – a thought was very much on my mind when I decided to go for my CrossFit certification.

If you've read Chris Shugart's comprehensive and even-handed article, you know that CrossFit has lots going for it, offering total-body conditioning with workouts that are never repetitive or boring. You also know it has some serious drawbacks, particularly the high potential for injury, since in some of the workouts you're doing high-effort, high-skill exercises for high reps in a state of near-complete exhaustion.

For something that risky, you want an instructor who knows what he's doing. Right?

As it happens, a lot of people want to become certified CrossFit instructors. That's why you can find a CrossFit Level 1 certification seminar somewhere in the world on virtually any weekend. They usually sell out far in advance.

But what exactly do attendees learn? Do graduates of Level 1 certification have the knowledge and skills to train CrossFitters? And, at $1,000 per applicant, is this a better deal for the CrossFit empire than for the aspiring trainers?

I figured there was only one way to find out. I paid my $1,000 and attended a two-day weekend seminar.

In fairness, I should note that I'm not a hardcore CrossFitter. I do, however, enjoy the occasional Workout of the Day as a change of pace, and I know enough about fitness to appreciate much of what the system offers.

So I went into this with two goals: the obvious journalistic mission, to report what goes on; and the less obvious fitness-nerd quest, to learn something that I can apply to my own training and that expands my overall base of knowledge.

Taking the Pipe

I arrived 20 minutes early at the Moss Park Armory, a Canadian military-reserve facility in downtown Toronto, Ontario. The classroom was already packed with CrossFit enthusiasts of all ages, genders, and body sizes. There was coffee on the breath and energy to spare.

The first instructor we met was Chuck Carswell, a charismatic former Division I college football player and head trainer for CrossFit HQ. He introduced the other coaches, and then jumped into the first lecture: "What Is CrossFit?"

The answer is simple enough – "constantly varied functional movements executed at high intensity" – but the explanation is interesting. Failure, Carswell told us, "occurs in the margins of experience." You get good at the things you like to do and suck at the stuff you avoid, so the seemingly haphazard nature of CrossFit programming is an attempt to challenge as many different movement patterns and energy systems as possible.

You do lots of squats, deadlifts, and pull-ups, and avoid single-joint movements like curls and extensions. You work really hard and you get really fit.

Fitness is defined with 10 basic markers:

- cardiovascular conditioning

- stamina

- strength

- flexibility

- power

- speed

- coordination

- accuracy

- agility

- balance

The goal is to be good, but not great, in each area – to be able to run three miles, do 100 push-ups, climb a rope, lift impressively heavy weights. Most of us can do one or two of those things but not all of them. That's because we've specialized in the activities we're good at and enjoy, while allowing ourselves to become deficient in the others.

The bottom line, which I think we all agree with, is this: doing things you hate often pays greater dividends than doing things you love.

The next subject – how to teach the squat – was impressive and practical. I liked the instructor's emphasis on making sure all clients squat below parallel, something you won't find in many personal-training manuals.

Some useful tips and reminders:

- If your knees fold inward during a squat, your adductors and glutes aren't firing correctly.

- On the front squat, start the movement from the bottom position by driving your elbows up. That helps you keep your chest in the upright position.

- Poor stability will keep you from getting proper depth on overhead squats. You can create midline stability by pulling on the ends of the bar, as if you're trying to break it apart. The tension in your traps and shoulders helps solve the problem.

Following the classroom lecture, we went into the auditorium to break into small groups and practice what we just learned, using a PVC pipe instead of a barbell. I'll give them this much: 20 minute of hands-on instruction is more than you get with most certification courses. But, still, it's 20 minutes with a PVC pipe. It's hardly sufficient for someone to learn to squat properly, much less teach it to others.

Getting a Feel for Fran

Over the break, I took the opportunity to meet some of my classmates. Most were either CrossFit affiliate owners from across Canada, or people interested in becoming affiliates. But there were also a surprising number of former and current military personnel. Paul Park, a Canadian Forces reservist who recently returned from a six-month deployment in Afghanistan, said that CrossFit is quickly becoming the training modality of choice for the Canadian Forces. "CrossFit is huge with Canadian troops and even more so with the American forces," he told me. "It's currently being indoctrinated into the training manual for the Canadian Forces. There are even CrossFit gyms opening up in forward operating bases like Kandahar."

Why do they like it so much? "It's the training system that best prepares you for a real-life situation."

Of course, your definition of a "real-life situation" will probably be different from Park's. Case in point: Fran.

Each CrossFit WOD – workout of the day – has a female name. Carswell's call to "go knock out Fran" met with rousing applause and cheers from the attendees.

Fran is one of the classic CrossFit WODs, and it's deceptively simple: 21 barbell thrusters with 95 pounds (a thruster is a combination front squat-push press), followed by 21 pull-ups, then 15 thrusters and 15 pull-ups, then 9 thrusters and 9 pull-ups, all done against time. The record is around three minutes or so.

Simple? Absolutely. Easy? Not so much. Preparing you for anything you're likely to do in this life? Again, it depends on the life you happen to lead.

I exploded out of the gate but quickly fell behind, and after 10 minutes was still struggling to finish before the instructors mercifully ended my first date with Fran. Was I really this lame? What gives? I can do chin-ups with a 60-pound dumbbell between my legs, but I need a calendar to clock my Fran time?

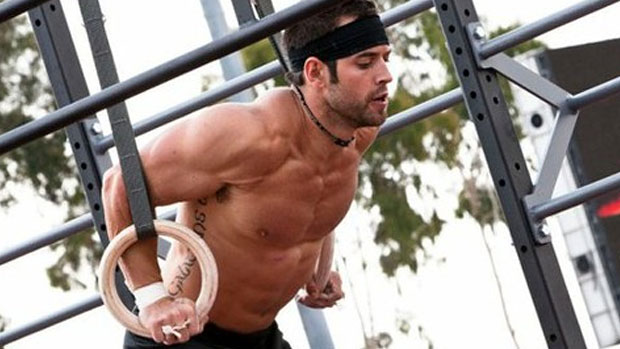

Looking around, I noticed that the other people still toiling away all had a few things in common: greater than average body size, a tendency to perform the lifts with slow eccentrics and controlled tempos, and poor ability to perform the kipping pull-up (which is shown and discussed here).

My Poliquin-approved four-second eccentrics may be great for strength and hypertrophy, but they sure sucked ass for CrossFit. I hoped I wouldn't have to hook up with Fran again anytime soon.

Sloppy Seconds

I arrived for the second and final day still smarting from my failed Fran experience, but also a little confused. The instructors had painstakingly taught correct technique, yet during Fran, some of the form I saw on the thrusters was pretty ugly. Why weren't the instructors calling this out?

As luck would have it, the first order of business was to discuss strength vs. technique. Pat Sherwood, our instructor, began with a CrossFit riddle:

If an athlete gets pinned under 225 pounds in the bench press, but three months later can successfully press 225, did he get stronger?

Collective nods.

If the same athlete fails at performing a muscle-up (an extended pull-up in which you finish with your arms straight), and three months later is successful, did he get stronger?

A few head nods, but also some disagreement. I joined the dissenters. "That could be just improved technique, through practice and repetition," I said.

According to CrossFit, I was wrong. "The athlete is stronger because in CrossFit, strength is the productive application of force," Sherwood explained.

Technique be damned?

"Unsafe is unacceptable," Sherwood said. "But perfect form is also unacceptable. What we look for is CrossFit slop."

If you're doing a high-rep, high-effort set of cleans, and your back starts to round, that's unsafe and therefore unacceptable. But if you're doing that same set of cleans with textbook-perfect form on every rep, that's also unacceptable. You've either chosen too light a weight, or you're not working hard enough.

The sloppy ideal is a small breakdown in technical form, maybe 20 percent off from perfect. In CrossFit, that's the optimal balance of effort and safety. "That's where the intensity is," Sherwood said.

I got it, but I wasn't buying it. Other coaches I've worked with were sticklers for impeccable form. Hell, Poliquin would stop a set for a breach of tempo, even if my form was perfect. He'd shit hypertrophied bricks if a client's form strayed 20 percent from the ideal on an Olympic lift.

To my mind, lifting is a learned endeavor. You practice perfect form over and over until it becomes second nature. That's especially true for Olympic lifting. How can you get good at an exercise if you force yourself to keep a set going past the point of technical breakdown? Aren't you just creating poor muscle-recruitment patterns that compete with the correct patterns?

"Technique only has to be good enough to increase the intensity," Sherwood answered. "The goal is never perfect form. Remember, it's the speed of the set that is the goal."

Fuel for Slop

In a typical certification program, the subject of nutrition is like Opposite Day. If you want to pass the test, you answer the questions the way you know the organization wants them answered – which, as often as not, is the opposite of how you would actually approach nutrition for performance, health, or physique improvement.

So I was pleasantly surprised when Sherwood started his nutrition lecture with some sensible assertions:

- No matter how intensely a client approaches his workouts, if he isn't diligently monitoring his food intake, he'll never get the results he wants. No arguments from me.

- For the entry-level trainee, it's best to keep it simple: "Eat lean meat, vegetables, nuts, seeds, some fruit, little starch, and no sugar." So far, so good.

- For the client at the next level of dedication, CrossFit recommends Barry Sears' Zone diet. Not my favorite plan, but okay.

- For the truly committed, you combine the first two strategies: clean food with a structured system of apportioning macronutrients. I figure this is what most T Nation readers are already doing.

But then it all went bad.

Following a discussion of how the typical high-carb, low-fat diet is an insulin-laden nightmare, a couple of mystery meals were broken down into their respective protein-carb-fat block values.

The first mystery meal was disproportionately high in carbs, and was revealed to be a government-approved "healthy" breakfast of oatmeal, fruit, and juice. The second meal, clocking in with a more Zone-friendly macronutrient ratio, was the clear winner: a McDonald's Quarter Pounder with Cheese.

I almost dropped my pen. Zone values notwithstanding, were they actually endorsing a Quarter Pounder as a healthy food item? Low-quality, mystery-meat protein, trans-fat-laden processed cheese, a bun made of refined flour, and who knows how many chemical additives and preservatives – that's a correct food choice? If you're going to pull my leg, at least yank the one in the middle so I enjoy it.

I realize it wasn't used as a recommended staple of your daily diet, but I still think it was a bad call. Many people who attend these courses are just getting their feet wet as fitness professionals, and find nutrition complicated and frustrating – every day is Opposite Day, with a continual tension between what you're supposed to recommend and what you think will actually work for you and your clients.

These entry-level trainers are often very susceptible to the quick-and-dirty takeaway message, and it was frustrating that two of those messages directly contradicted each other. How can anyone reconcile "eat lean meat, vegetables, nuts, seeds, some fruit, little starch, and no sugar" with "a Quarter Pounder with Cheese is better than oatmeal, fruit, and juice"?

Methodical Madness

Toward the end of the second day, we finally got to the biggest question many of us have about CrossFit: What's the logic behind the WOD? Is there a method to the madness, or is it utterly random?

Answer: It's both.

CrossFit breaks exercises down into three categories:

- Weight lifting: cleans, push presses, deadlifts, front squats – anything using added resistance.

- Gymnastic: dips, pull-ups, push-ups, box jumps – all done with body weight only.

- Monostructural: sprinting, skipping, rowing – continuous or intermittent movements that most of us would classify as "cardio."

Next, there are three different workout templates:

- Singlet: just doing one of the above. Seven sets of deadlifts is an example of a singlet workout.

- Couplet: two of the above. Fran, which combines a weight-lifting exercise (thrusters) with a gymnastic exercise (pull-ups), is a couplet workout.

- Triplet: all three categories. An example might be a 400-meter run, 21 kettlebell swings, and 12 pull-ups.

According to the instructors, the number-one mistake a new CrossFitter makes is overprogramming, or making the workout far too challenging. The next-biggest mistake is blowing off the low-rep singlet days altogether in favor of the "puke in your shoes" couplets and triplets. If you're training five days a week, the instructors suggest at least one singlet workout.

And that's that. It's simple, succinct, and practical. But is it effective? Most of those in attendance seemed to think so, but I wasn't so sure. And some former CrossFit coaches I spoke to shared my skepticism.

Darren Mehling is a CrossFit affiliate who does his own thing at his facility, Freak Fitness. Mehling sees a lot of merit to the CrossFit system (he's Level 2 certified), but is also quick to point out its shortcomings.

"I deadlift 800 pounds and squat 600," he said. "It took me over 15 years to get that strong. When I first performed Fran, it took me 16 minutes. But within five months, I could do Fran in less than four minutes. Basically, I just needed to get good at doing CrossFit."

I've heard similar arguments from other coaches. If someone trains to get strong in the traditional sense, not only does maximal strength improve, but strength endurance improves as well. If someone just trains for strength endurance, he merely improves his performance at his current level of strength. He can't improve his maximal strength without focusing on it.

As mentioned, CrossFit programming tries to mitigate this effect by scheduling periodic low-rep, max-effort days, but how much stronger can an intermediate or advanced lifter get if he only trains for strength once a week? And that's assuming the trainer running the CrossFit facility isn't skipping those strength workouts altogether.

Mehling has experienced that firsthand. "Strength training isn't fun to most CrossFitters, and a lot of them don't want to do it," he told me. "And let's be brutally honest: It's easy for one coach to run a stopwatch and yell 'go, go, go' to 30 people doing Fight Gone Bad. Can you imagine one coach trying to simultaneously teach 30 people to do heavy triples in the squat?"

The Final WOD

Our day concluded with a WOD. This time, it was 10 box jumps, a 50-yard dash, 15 push-ups, and another 50-yard dash, repeated for 10 minutes. It wasn't textbook CrossFit, but it served as an example of what you can accomplish with minimal equipment. (It was also kind of a madhouse, with 50 people sprinting and box-jumping all over the place.)

This time I focused on moving as fast as possible, without thinking about maintaining any particular tempo. It made a world of difference, and 10 minutes later I was thoroughly smashed but curiously invigorated. Anyway, it beats the shit out of 10 minutes on a treadmill or stationary bike.

As I left, freshly certified as a CrossFit Level 1 instructor, I came to these conclusions:

- The system clearly has value, but how much value depends on your goals. As a one-stop fitness and conditioning system, CrossFit is an excellent choice. The workouts are challenging and competitive, and jack up the heart rate deceptively fast. The fact that they rely upon basic, functional lifts is a plus as well.

- My absolute favorite thing about CrossFit is that it forces people to work hard. A lot of lifters don't work nearly as hard in the gym as they think they do.

- No matter what anyone tells you, you'll never get truly strong doing CrossFit. Sure, you might get stronger than you are now, but if maximal strength is your goal, keep shopping. If you don't believe me, email Dave Tate and ask him what his Fran time is.

- You won't get bigger doing CrossFit, which could be absolutely fine if your goal is fat loss or overall conditioning. But you might look bigger, if you have a lot of muscle beneath your fat and CrossFit helps you burn the fat off.

- Mixed martial artists and military personnel – especially members of elite special-forces units – should definitely do something a lot like CrossFit. There are probably ways to make it more specific to their needs as athletes and warriors, but the idea is exactly right for what they do.

- Many bodybuilders could benefit from occasional CrossFit workouts. The system is so challenging, and so different from traditional paradigms, it might be a perfect shock to someone in the body-part-training rut. Plus, for those in a cutting phase, one or two CrossFit workouts a week could be a great fat-loss tool.

- The random program design doesn't make long-term training sense. As noted by Alwyn Cosgrove in the earlier T Nation article, potential overexposure of the shoulder joint to frequent heavy loads and high volumes is a real concern. While hardcore CrossFitters may scoff, I'd like to check back with them after a few more years of CrossFitting.

- The notion of CrossFit slop is potentially injurious, especially for those new to Olympic lifts. I just can't think of a good justification for it.

- A Quarter Pounder with Cheese is shit, no matter how Zone-friendly its macros turn out to be.

Now for the thousand-dollar question: Do I have the ability to apply the skills I learned in the two-day seminar? I think so, but that's because I had a lot of training knowledge and experience going in. If an experienced CrossFit trainer asked me to help out with a class, sure, I think I could do that. I don't think I could teach a roomful of rookies how to perform a snatch, but I'm not really sure anyone could.

Perhaps the better question is, would I trust my health and safety to any randomly chosen individual simply because that person was CrossFit certified? Absolutely not. We were never formally tested in any of the lifts we learned, and everybody passed. This is a sharp contrast to my experience in Poliquin's course, where attendees would fail for simply forgetting to have their wrists cocked back in the preacher curl.

Now, if you'll excuse me, I think I'm going to take another run at Fran.

Pass the Kool Aid.