Hardcore Health

You lift heavy things. You believe there's no illness that heavy squats can't cure. Heck, you're so hardcore you consider creatine a garnish.

But let your health slip and it's bye-bye big muscles and new PRs. To prevent the slip, you may need a few physical assessments.

When it comes to assessments, there are a few schools of thought. On one end of the spectrum you've got trainers who spend two days assessing someone, taking meticulous notes on everything from how much someone's left big toe pronates to rectal temperature.

At the other end, you've trainers who don't know their ass from their acetabulum, and so long as their client can stand on two legs they're good to go, oftentimes leading to disastrous results.

As always, the best approach lies somewhere in the middle.

What follows are some of the common weaknesses and imbalances we often come across at Cressey Performance during the initial assessment process. These are things that, left unchecked, can either really mess up your lifting, create aesthetic "holes" in your physique, or leave you pain-stricken and lying in a hospital with a catheter and bed pan.

But being aware of your weaknesses is only half the equation. You'll need to know the most practical, effective ways to start fixing those weaknesses to get on the fast track back to being a badass.

Lack of Ankle Dorsiflexion

Poor ankle mobility is a very common weakness. The main issue stems from our affinity to provide "false stability" to a joint that normally wants to be mobile, like taping ankles or wearing those cement blocks we like to call shoes.

Optimally, the ankle should have roughly 20 degrees of dorsiflexion – think pointing your toes towards your shin. If you don't have it, it's going to make performing a squat or lunge pattern pretty difficult.

When we lack ample dorsiflexion, a whole host of issues can arise, including anterior knee pain, hip pain, and lower back pain. So fixing it can go a long way in keeping people healthy in the long run.

While I can typically just watch someone squat and tell whether or not he or she has ample ankle mobility (those who lack it tend to be "ankle squatters" and push their knees forward excessively), one of the simplest ways to actually test for it would be the wall ankle test.

Wall Ankle Test

- Stand in front of a wall with the toes of one foot against it.

- Making sure to keep the heel on the ground, simply "tap" your knee to the wall.

- Move your foot back a half inch and tap the knee again.

- Keep moving the foot back little by little, tapping the knee to the wall, until you can no longer keep your heel down.

Ideally, you should be at least three or four inches from the wall. Anything under that and you may be asking for trouble.

To correct it, repeat the test, which is now a suitable drill. Just throw the wall ankle mobilization in as part of a warm-up and you're golden.

Lack of Hip Internal Rotation

You have roughly 30 muscles that attach to the pelvis alone, so it stands to reason that the hips are a problematic area for just about everyone.

Hip internal rotation deficits are a key player in things such as lower back pain, knee pain, and even contralateral shoulder pain, but what's surprising is the role that adequate hip IR plays in squatting. Basically, you need a certain amount of internal rotation to effectively go into deep hip flexion.

Hip IR should be tested in two postures, because different structures can limit range of motion depending on whether the hip is extended or flexed.

Seated Hip Internal Rotation

- Sit at the end of a table, with your knees bent over the side, and hold onto the table itself.

- Now internally rotate the hip, without abducting or side bending, which is a sign of compensating with the lower back.

Generally speaking, a minimum of 35 degrees is what we're looking for in the general fitness population. Comparatively, with rotational sport athletes, we're looking for a minimum of 40-45 degrees.

Prone Hip Internal Rotation

Additionally, we want to test hip internal rotation in the prone position because as physical therapist Bill Hartman has noted on several occasions, it helps to differentiate whether we're dealing with a capsular issue or a muscular issue.

- Lie on your stomach and flex both knees to roughly 90 degrees, then internally rotate your hips. Keep both knees together.

If seated hip IR is limited, and prone hip IR limited, then Houston, we have a problem.

If seated hip IR is limited, and it improves with prone hip IR, that's a little better as you know you're probably dealing with more of a muscular issue and not capsular.

Here are my favorite drills to improve hip internal rotation:

Prone Windshield Wiper Stretch

Much like the prone hip IR test itself, the setup for this stretch is the same, except here you'll lie prone on a table (or floor) and only flex one leg.

- Reach back, grab your heel, and pull towards your butt.

- Gently push your lower leg into external rotation, which in turn will stretch the hip into internal rotation.

- Hold for a 20-30 second count and repeat on the opposite side.

- Note: If you feel any discomfort or pain in the middle (inside) aspect of the knee, try to be less aggressive with the stretch and not push down as hard. This should be a subtle stretch.

Seated Passive Internal Rotation Stretch

This is one I snaked from Dean Somerset, a strength coach up in Canada. It looks at passive hip internal rotation while in hip flexion. As Dean notes, though, the downside of this stretch is that if the posterior capsule or musculature is stiff or tight, this position will be limited.

For some, this may be a more advanced stretch. If that's the case, stick with the aforementioned prone windshield wiper stretch.

- Sitting at the end of a treatment table, lift one leg back into hip internal rotation.

- From there, grab your ankle and gently lean into the stretch, progressively working your way closer to the table.

- Hold for a 30 second count and repeat on the opposite leg.

Half-Kneeling Hip IR/ER Mobilization with Band

- Wrap one end of a standard band around a power rack and the other around your knee.

- Now actively "pull" yourself into hip internal rotation, and then reverse the direction into external rotation.

- Perform 8-10 reps on one leg, then switch.

Hip Stability (or lack thereof)

Hip stability is seriously lacking in a vast majority of trainees. I've seen powerlifters who routinely throw 800+ pounds on their backs struggle to perform a basic bodyweight reverse lunge due to poor hip stability.

Poor hip stability can cause a multitude of issues ranging from lower back pain, knee pain, and even shin splints. It'll affect performance in the weight room and seriously limit the amount of iron you can lift safely.

While there are several tests you can do to assess hip stability, bilateral or two-legged assessments don't make much sense because our legs end up doing all the supporting. When the body is supported on one leg, as it is while walking, the body must be stabilized on the weight-bearing leg during each step.

In a single-leg stance, the body is forced to fire what's been termed the lateral sub-system (adductors and abductors of the standing leg, and the quadratus lumborum of the opposite leg) to stabilize the pelvis. What you'll see is the affected side going into hip adduction because the hip abductors are too weak to stabilize the pelvis on the femur.

A more functional drill we can use to test hip stability is the single-leg squat:

- Stand on one leg (preferably barefoot) and squat to roughly 60 degrees of knee flexion.

- If the midline of the knee stays in line with the midline of the foot, you're a rockstar. If, however, the knee caves in or deviates medially, then you're most likely dealing with a weak glute medius.

To fix it, there are two key drills I use. The first is the side-lying clam, which is a simple exercise but easily butchered by most trainees.

- Rotate your top hip towards the floor to help prevent compensation by the lumbar spine. If you watch the video carefully, you'll notice that after I flex both my hips and knees, I sorta take my top hip and "close it off."

- Don't be too concerned with range of motion here. The important thing is that you do it right!

- If you happen to walk past an attractive female doing this exercise, please, for the love of God, act like you've been there before and refrain from making honking noises.

- Perform 2-3 sets of 8-10 repetitions on both sides.

Taken from strength coach Brijesh Patel, the second exercise is definitely one of my favorites because not only does it integrate and strengthen the feet, but also trains hip stability in multiple planes.

- Stand on one leg (barefoot) and perform 5-8 repetitions in each plane (saggital, frontal, and transverse).

- Try to keep your weight in the middle of your foot and not your toes.

- Be sure to keep the midline of the knee in line with the midline of the foot throughout.

- Ideally, you want to perform all reps without the other foot touching the ground, but I won't think any less of you if this isn't doable.

- When performing this drill in the transverse plane (rotating), be sure to move through the hip and not the lower back.

If this is too easy, you can make it more challenging by adding a reach into the mix.

Poor T-Spine Mobility

Mike Boyle notes in Advances in Functional Training: "The important thing about t-spine mobility is almost no one has enough and it's hard to get too much."

It's important to reiterate that adequate spinal mobility, particularly in the thoracic spine, is essential for normal shoulder function. Lack of t-spine mobility can have deleterious effects ranging from poor length-tension relationships (which can effect proper scapular positioning and stability), to preventing adequate extension (which will undoubtedly affect shoulder range of motion).

I'd go so far as to say that if you spent more time working on your crappy posture, you'd see vast improvements in things like your bench press, not to mention the likelihood that someone of the opposite sex will want to see you naked. With the lights on.

A kyphotic posture (rounded upper back) leads to anterior tilt of the scapulae and poor t-spine mobility. As a result, this places you in a very unstable position to push anything away from your chest, much less a bar with a lot of weight on it. Essentially, it's like shooting a cannon from a canoe.

So, if we improve t-spine mobility, we can affect scapular positioning (a return from anterior tilt) which provides a bit more stability, and good things will happen.

A favorite test of ours is the lumbar locked rotation. Popularized by Greg Rose of the Titleist Performance Institute, the lumbar locked rotation test is a bit more advantageous because it doesn't allow for any cheating.

Namely, by sitting back and "locking" the lumbar spine into position, we can't use it to produce more range of motion. In a sense, we're forced to move through our mid-back/thoracic spine, which is the purpose of the test in the first place.

- Start in the quadruped position and sit back onto your calves.

- Place your hands behind your back and rotate to one side.

For general population clients, we're looking for anywhere from 50-70 degrees of rotation. Comparatively, for rotational sport athletes, we'd want to see 70-90 degrees – although 90 degrees is freaky.

If you find that your t-spine mobility needs work, (and trust me, it needs work), try implementing these drills throughout the day or before you train.

Side Lying Windmill

The video is pretty self-explanatory. The only caveat I'd make is that you want to make sure the top leg is at 90 degrees of hip flexion and resting on either a medicine ball or foam roller to prevent lumbar rotation. Also, when you bring your arm up and around your head, be sure to follow it with your eyes all the way around.

Wall T-Spine Dips

This is another great drill to help improve t-spine mobility, specifically extension:

- Stand in front of a wall and place the back of your upper arms against it.

- From there, take a deep breath and "dip" into the wall by pushing your arms up and away.

- Return back to the starting position and repeat.

Lack of Shoulder Flexion

There are numerous things that can affect shoulder health and function. Having the ability to raise your arms over your head is one of them.

Having ample t-spine extensibility plays a huge role here. I mean, round your back and try to raise your arms over your head. Kind of hard, right?

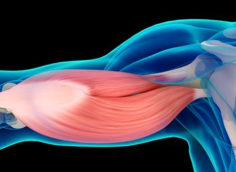

Another aspect that often gets overlooked are the lats. The latissimus dorsi arguably have the greatest affect on human locomotion of any other muscle in the body due to attachments points on the humerus, scapulae, ribcage (breathing patterns), thoraco-lumbar fascia, posterior iliac crest, and the lumbar spine.

The lats actually have a profound influence on our ability to push, pull, and squat big weight. Concurrently, with respect to shoulder flexion – namely, our ability to lift things over our head – having "tight" lats will force someone to compensate with their lower back and go into hyperextension.

This might help explain why many trainees tend to turn an overhead press into a glorified standing incline press. It would also explain why people with limited shoulder flexion oftentimes have chronic lower back pain.

Testing for tightness of the lats is easy:

- Lying on your back, start with your arms on your side, elbows extended, and knees bent (to flatten the lower back and provide more of posterior tilt).

- From there, raise both arms over your head and bring them down towards the table while maintaining a flat back.

- If you're able to bring your arms down to table/floor level, keeping arms close to the head, you pass. However, if you're unable to bring your arms to table/floor level, you suck at life and should just jump out of a window and land on a sharp object.

How to Fix It

First off, foam roll your lats:

- Lie on your side and place a foam roller right in your armpit.

- From there, roll down your lat (not your ribcage, you can't foam-roll bone) and spend a good 30 seconds on each side. For those with tight lats, this won't be pleasant.

Next is the wall lat mobilization with stabilization:

- Reach across your body and push against the wall.

- With your opposite hand, grab your shoulder blade and pull down to lock it in position.

- Next, all you're going to do is sit back until you feel a nice stretch in your lat.

- Hold for a two-second count, return back to the starting position and repeat for a total of 6-8 reps on each side.

Assess and Address

If staying healthy and continuing to make progress is important to you, try some of these assessments and see if any "red flags" arise. You'll be happy you did.