I like to be strong, but I don't wear three-ply titanium shirts

and compete in bench press competitions. No, I like to be strong

because that helps me build muscle. I like to sprint too, but I

have no hopes of winning medals in track & field events, and I

don't play any sports. Nope, I only sprint because it makes my ass

all round 'n perky.

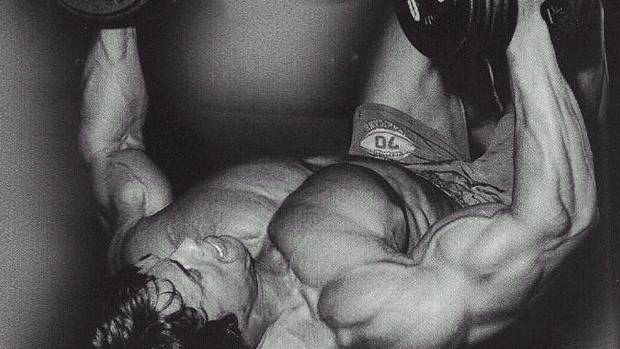

See, I lift weights mostly for egocentric, superficial reasons:

I do it to look good and feel good. I do it because those old black

and white pics of Arnold inspire me. I do it because being fat and

"skinny fat" doesn't turn the heads of women.

|

I'm sorry. I apologize profusely for loving good ol' aesthetic

driven bodybuilding. I am so ashamed.

Okay, not really. I'm not ashamed at all. In fact, I sometimes

think we forget about bodybuilding. Many Testosterone Nation

writers are mainly focused on performance. That's cool, because

performance goals often lead to "looking good naked" goals, but I

honestly couldn't care less about how some shot putter or

drugged-up powerlifter trains. It ain't my bag, baby.

That's why I think Christian Thibaudeau is one of the best

"bodybuilding coaches" out there. He has the background in

performance training; he knows a whole lot about speed and power

and strength. He can quote lots of fancy European studies.

But he's also a bodybuilding historian, he's trained competitive

bodybuilders, he's struggled with fat-boy issues, and he's stepped

onto the stage himself. This makes Thibaudeau, well, the "perfect

storm."

|

When I have a question about pure aesthetic lifting, I turn to

Thibaudeau. Hence the straightforward idea for this interview:

questions about bodybuilding. Here's what I learned.

Testosterone Nation: Let's start with some info on genetics.

While everyone can build muscle, it seems that some people can do

it at ten times the rate of others. They also just keep getting

bigger while most average people reach a ceiling on their

development. Assuming there are no steroids involved, what genetic

issues go into building a big, muscular body?

Christian Thibaudeau: I think that we have four aspects to

consider. First, we have the muscle tissue composition itself.

It's not a big secret that fast-twitch muscle

fibers/high-threshold motor units have a much greater growth

potential than their slow-twitch/low threshold counterparts.

So in that regard, an individual with an unusually high level of

high-threshold motor units will have an easier time gaining muscle

mass. We could also include insertion points/muscle belly length in

the muscle composition category. Longer muscle bellies have a

greater potential for growth than shorter ones.

|

Then we have the hormonal factor. People vary widely in their

natural capacity to produce various anabolic hormones

(Testosterone, growth hormone, IGF-1, etc.) and in their

sensitivity to these hormones. Being sensitive to the various

anabolic hormones means that your body will react to a greater

extent to even a small elevation.

This sensitivity issue explains in part why some individuals

blow up when they use small doses of steroids while others gain

little muscle mass even with very high doses. I know several gym

rats who take much higher doses than a lot of top pros and hardly

look like they train at all! I also know some top amateurs and pros

who actually use very little anabolic support. Obviously, someone

who naturally has a higher level of anabolic hormones or is more

sensitive to them will be able to build muscle at a faster

rate.

The third aspect is the nervous system, and it might very well

be the most important one of all since it's the one in which

we have the greatest control. To maximally stimulate growth in a

muscle, you must be able to recruit as many high-threshold motor

units (HTMUs) as possible. And not only do you have to recruit

them, you have to fully fatigue them. A more efficient nervous

system means better efficacy at recruiting these HTMUs.

When someone has a lagging muscle group, more often than not

it's due to an inefficient neural activation in that muscle group.

It's tempting to blame muscle fiber dominance for lack of

growth in certain muscle groups ("My XYZ is slow-twitch

dominant so it can't grow no matter what"), but except

for a very few extreme cases, most individuals will be at least

40-50% fast-twitch in most muscle groups.

While this won't allow them to grow as fast as someone

who's 80-90% fast-twitch, it does mean that all of their muscle

groups do have the potential to gain size. So except for the few

rare cases of actual slow-twitch dominance (80-90% slow-twitch),

when a muscle group is lagging it's mostly due to an inability

of the neuromuscular system to fully recruit the HTMUs.

The fourth and final aspect is a psychological one: tapping into

these HTMUs requires a tremendous level of effort in the gym as

well as a high pain tolerance. People who aren't motivated and

aren't giving it 100% in the gym will obviously have a harder time

stimulating muscle growth. Simply lifting the bar from point A to

point B won't stimulate muscle growth; it's what happens in

the muscle and in the CNS that'll dictate how much muscle

you'll gain.

T-Nation: Doesn't arm and leg length also play a role in "jacked

potential?"

Thibaudeau: Obviously, other factors such as limb length will

play a role in muscle growth potential too, or more precisely in

giving the illusion of size. An individual with shorter limbs won't

have to gain as much size on his arms for them to look big. A guy

with super long arms will have a harder time making them look

impressive.

But the first four factors are the most important ones when it

comes to your actual capacity to build muscle tissue. However, your

body structure can influence the way you look, independently of the

muscle size aspect of it. For example, people with a wide clavicle

and narrow hips will look much more muscular than they actually

are. Those with a narrower clavicle and wider hips won't look as

good as their level of muscularity normally would.

T-Nation: Okay, one of the most common questions

aesthetic-minded lifters have is, "Should I bulk or cut?" Any

guidelines there?

Thibaudeau: As you know, my article against all-out

bulking caused quite a stir here at T-Nation! But I think that a

lot of people didn't get the actual message behind it.

My belief is that you can't build a lot of muscle without

consuming a caloric excess, or more precisely, consuming more

nutrients than you use up each day. I think we can all agree with

that. However, you can't force feed your body into building more

muscle, especially if you're natural.

Your body is limited by its own physiology/biochemistry when it

comes to building muscle mass; it has a certain capacity to take

the nutrients ingested and turn them into muscle tissue. If you're

not eating as many nutrients as you can utilize for growth each

day, you'll benefit from increasing your caloric intake (you'll

gain muscle faster). But once you reach the nutrient utilization

ceiling of your body (which is determined mostly by the level of

anabolic hormones in the body), simply adding more calories or

nutrients won't lead to a faster rate of growth.

(Obviously, chemically enhanced bodybuilders face a different

reality since the anabolic support they use will allow them to push

that utilization ceiling upwards by bypassing their natural

biochemistry.)

So what I'm against is a caloric intake that's drastically above your daily needs. If you have a daily

energy expenditure of 3000 kcals/day, you probably have a

utilization ceiling of around 3750-4000 kcals (could be more or

less depending on your hormonal status and metabolic rate).

Increasing your caloric intake from 3000 to 4000 kcals will indeed

lead to a faster rate of muscle growth, but going from 4000 to 5000

kcals/day will likely not result in any additional muscle tissue,

but it will lead to more fat being gained!

So if your main objective is to gain muscle mass, you have to

eat more nutrients than you use each day, but you shouldn't

eat so much that you end up gaining more fat than muscle. You

should stay at a level that allows you to at least look decent

"nekid" and only a few weeks of dieting away from being in good

shape.

|

Obviously we must also consider the level of development of an

individual. A beginner with basically no muscle mass will probably

need to accept a bit more fat gain as he builds up his muscle base

than someone who's already in very good shape. However, I still

think that we should avoid gaining an unacceptable amount of fat

for the sake of adding muscle.

Now, what's unacceptable will vary from one guy to the next. I

personally don't like being above 10% body fat and actually

stay closer to 8% year round. Other people still look and feel good

at 12-14%. It's an individual thing.

But regardless of your caloric intake, or if you're bulking or

cutting, you should stick to clean food 90% of the time. I still

believe that "bulking" shouldn't be used as an

excuse to pig out on junk food.

T-Nation: You know someone is going to post a picture of an

unhealthy, heavy steroid user and say, "Oh yeah, this guy eats Big

Macs all day and look at him!" In fact, I have a photo of the

people who say that:

|

Moving right along... It seems that a lot of gym rats want to

specialize on body parts too soon. And that brings us to the "stick

to the big basics" vs. specialization training debate. Any advice

there? When should a person start worrying about bringing up

certain body parts?

Thibaudeau: Beginners obviously shouldn't specialize. They

don't need to, especially since most of the time any perceived

weaknesses might simply be due to improper training in the past

(e.g. only training the "mirror muscles") or to the

previous activity background. For example, someone who spent years

practicing alpine skiing will have dominating legs right off the

bat, but that doesn't mean he shouldn't train his legs

when he begins lifting weights.

At first, everybody should use a balanced training program. That

doesn't mean only "sticking to the basics." In fact,

sticking to the basics can actually go against the balanced

training philosophy! Someone with strong shoulders and triceps

might under-stimulate his pectorals if he only uses "the

basics" (only performs heavy pressing movements for the

chest). Another guy with powerful biceps might not fully stimulate

his back if he only uses "the basics" (only performs

pulling movements for the back) since the biceps will take over in

the movement.

Beginners should learn to properly activate and stimulate every

major muscle. This will prevent any future problems with the

CNS's capacity to recruit a muscle group. To do this,

beginners need to use both basic lifts and isolation/focused

movements to make sure that every muscle group is properly

stimulated.

T-Nation: Okay, so specialization should only be used by

individuals who already have a good foundation of muscle. But what

constitutes an acceptable level of muscle mass?

Thibaudeau: Well, that's an individual thing, but I think

that someone should gain at least 20 pounds of muscle mass with a

balanced approach before even considering specialized training. And

even then, specialization shouldn't be abused. It's a

strategy specifically designed to bring up a lagging muscle group

by hitting it often (to improve the CNS's capacity to recruit

it). As such, it's best used by bodybuilding competitors or

individuals with an obvious imbalance.

Specialization can also be used by individuals with a postural

problem. For example, if someone has a severe shoulder anteriority,

specializing on the back, rear delts, and external rotators is

probably a good idea, especially with athletes who can increase

their risk of injury if they have an incorrect

posture.

T-Nation: Interesting stuff. Now, visible abs have always been

important for the "artistic" physique, but these days everyone

wants that lower abs V-shape. What the heck is that muscle group

exactly and how do you get it?

|

Thibaudeau: This "V" is actually the tendons of the

external obliques as well as the lower portion of the rectus

abdominis.

|

So really, the only way to "get" this V-shape is to

train your obliques and the lower portion of your abdominals. And

of course, you have to get your body fat down to a fairly low

level.

The following exercise pairings could do the job, at least from

the muscular development standpoint:

Superset 1: High pulley woodchop (8-12 reps per side) and

twisting crunch (max reps)

|

|

|

|

Superset 2: High pulley crunch (8-12 reps) and leg tuck (maximum

slow reps)

|

|

|

|

On these last two exercises, try to activate the pelvis floor

(imagine having to pee and holding it in).

T-Nation: Cool. We always hear that to get big arms (or whatever

muscle group) we shouldn't use isolation exercises or machines too

much. But that's what every pro-bodybuilder does!

The experts basically tell us to train in the opposite manner of

how the best in the world train. That seems odd, doesn't it? I

mean, we're told that flyes are a sissy, worthless exercise, but

you know what? Every guy with an impressive chest I've ever seen

does flyes!

|

Thibaudeau: To develop a certain muscle group you must use the

exercises that provide the best growth stimulus for that muscle.

Depending on the muscle we're talking about, as well as the

muscular dominance of the individual, these exercises can be

multi-joint, isolation, or both types of exercises. We really

shouldn't divide exercises as multi-joint and isolation

anyway, but rather as "effective and ineffective"

exercises.

Take the chest for example. For the majority of gym rats, the

bench press is probably one of the most overrated exercises around.

Why? It's quite simple: the regular bench press is a lousy

pectoral exercise for most individuals!

I've rarely seen someone who focuses only on the bench press

have good pectoral development. Most of the time these individuals

will have big triceps and/or deltoids, but a very incomplete chest

development. They normally have a decent "outer portion"

but the pec gets thinner as we move toward the sternum. The

strongest bench pressers normally have underdeveloped pectorals

(compared to their other pressing muscles) unless they also perform

better chest exercises in their programs.

The powerlifting bench press is first and foremost a triceps

exercise. To make the bench press an effective pectoral movement we

must use a wide grip, flare the elbows out, and bring the bar down

to the collarbone (known as a neck press).

|

However, you can't use as much weight as with a regular bench

press. And for some people, the ego is quick to jump in and they

revert back to a less effective variation of the bench press. This

is why I wouldn't include the bench press on my list of the

most effective chest movements. But if you're able to leave your

ego at the door and perform a proper neck press, then it can be a

useful addition to a good pectoral program.

T-Nation: How about biceps? Again, there seems to be an

anti-curl trend going on, and while I agree that close-grip

weighted chins are awesome arm builders, I've also never seen a guy

with impressive biceps that didn't curl.

|

Thibaudeau: Yes, the same logic can be applied to the biceps. We

should select exercises not because they fall either in the

multi-joint or isolation category, but rather because they're the

most effective exercises to do the job... and that job is to

make the biceps grow!

To me there's no question that curling exercises are necessary

to develop the biceps to their maximum potential. If someone is

using heavy pulling movements to build their biceps, chances are

they're not doing these heavy pulling exercises properly and as a

result will get an inferior back stimulation. This will lead to the

faulty motor habit of over-stimulating the arms and

under-recruiting the back during pulling movements.

The best exercises for a muscle group are the ones that place

the targeted muscle group in a loaded stretch position prior to the

concentric portion. Remember that a stretched muscle is a recruited

muscle.

We can also increase biceps activation by increasing its

stabilization role while an arm flexion movement is being

performed. An example of this is a single arm barbell curl. The

long bar increases the need for stabilization, and that action is

provided by the biceps which will act as a static supinator.

In my opinion the best arm flexor exercises are (in no

particular order):

• Incline dumbbell curl. Fully stretch the biceps at the bottom

position. Don't rotate your arms. Start in a supinated (palms up)

position and curl that way too.

|

|

• Incline hammer curl. Again, fully stretch the biceps at the

bottom position. Don't rotate the arms. Start and end in a hammer

grip position.

|

|

• Behind back low-pulley curl. Again, aim for that maximum

stretch.

|

|

• Behind back low-pulley hammer curl

|

|

• One-arm barbell preacher curl. Very important to keep the bar

perfectly parallel to the floor.

|

|

• One-arm barbell curl. Again, very important to keep the bar

parallel to the floor.

|

|

You'll notice that in all of these exercises (except the

hammer variations) the wrist is either extended or neutral, to

focus more of the stress on the biceps. That's not to say that

there aren't any other great biceps exercises, but from

experience, these are the best ones out there.

T-Nation: Cheat movements: good or bad if your main goal is

building muscle?

Thibaudeau: It depends on what you mean by "cheating." If

cheating means using a faulty movement pattern to be able to lift

the weight from point A to point B, taking the tension off of the

target muscle group, then I'm against it, at least when it

comes to stimulating muscle growth.

When you're training to build muscle mass you aren't

lifting weights from point A to point B; you're contracting muscles

against a resistance. When the target muscle group is fried it's

possible to continue on with the set by relying on secondary

muscles. However, this won't have much benefit on the target muscle

itself. In fact, it may become detrimental as over time it could

lead to improper recruitment patterns where you have more and more

difficulty recruiting the target muscle group because you

over-relied on the secondary muscles.

|

Some will argue that if you cheat a little bit at the end of a

set you can get those extra two or three reps. Yeah, okay, I agree.

But these aren't "money reps" in that they

won't efficiently hit the targeted muscle group.

When a muscle reaches technical failure (when it can't complete

a task at the prescribed parameters) it doesn't make much

sense to continue to try to pound it. It's much more efficient to

add an extra set if you feel that the HTMUs haven't been fully

stimulated.

T-Nation: Okay, so instead of cheating out an extra couple of

reps, just add another set. I like that idea.

Next question: Arnold, at times, trained twice per day, adding

up to several hours in the gym five or six days per week. Today we

all know that spending over an hour in the gym is a waste of

time... and none of us are as big as Arnold. Coincidence? Have

we taken the "keep it to an hour or less" rule too far or is that

still good advice?

Thibaudeau: That could be a two part answer! First, I think that

we need to mention that Arnold only trained twice a day during his

pre-contest period. So basically only eight to twelve weeks out of

52. The rest of the year he'd train less often, three to five times

per week, not using double splits.

We also need to say that this was pretty much how most guys

trained during the pre-contest period at the time. In fact, some

guys trained much longer than Arnold did. For example, Pete

Grimkowski used to train as much as seven hours per day at the peak

of his career. Serge Nubret trained for three hours, plus one more

hour of abdominal work six days a week. Mike Katz would also train

four to five hours per day.

|

The thing is these guys didn't do much cardio to shed the

fat. The super-high volume of work increased caloric expenditure,

which helped them lose fat and get into contest shape. Nowadays a

lot of bodybuilders will do 45 minutes of cardio in the morning, a

weight training session in the afternoon, and a second 30-45 minute

cardio session at the end of the day.

So while they aren't doing as much weight training as the

old timers did, their level of physical activity is almost as high.

You also have modern bodybuilders who do train twice a day during

their pre-contest period, Jay Cutler being one

example.

To be honest, I don't see anything all that unusual about

this volume of physical activity. I come from an athletic training

background and I've worked with athletes who trained a total

of four to six hours per day, six days a week. Obviously that

wasn't all gym time, but it was time spent doing physical

work.

Figure skaters and gymnasts train around four to five hours for

their sport and this type of training is very physically demanding.

Then I have them in the gym for an hour three times a week. This

made for a total of around 30 hours of training per week. Go tell a

gymnastics coach that he shouldn't have his athletes train for

more than two hours, four times per week, and he'll have you

committed! For years and years, the better competitive athletes

have trained 20-30 hours per week with great

results.

When I worked as the head strength & conditioning coach for

a top sport/studies program, we had over 400 student-athletes from

26 different sports training with us. All of them trained at least

three hours per day, either in the gym, on the track, or on the

field. If elite athletes can not only survive but thrive on 20-30

hours of training per week, I don't see why a bodybuilder

couldn't train 10-16 hours per week in the gym.

The thing is that most bodybuilders, or guys training only to

gain muscle, are out of shape and have a very low work capacity.

This is probably directly due to the fear of overtraining. These

individuals can't jump into a very high volume of weekly training

without crashing and burning because their body isn't

accustomed to handling this kind of physical work.

Work capacity and exercise tolerance is something that's

gradually built over time. If you jump straight from three hours of

weekly training to 12 hours, yeah, you'll burn out! But it is

possible to train more and more as your body adapts to physical

work. In fact, the more you can train without exceeding your

recovery capacities, the more you'll progress.

So to recap:

• Old-timers had a super high volume of gym work because they

used the added strength work to lose fat instead of relying on a

lot of cardio.

• Old-timers used this approach only during the pre-competition

period to shed body fat, not really to gain muscle.

• Modern bodybuilders still perform a high level of physical

work in the pre-contest period, but the trend has shifted to an

increase in the amount of cardio and a decrease in lifting

volume.

• If you train more, without exceeding your capacity to

recover, you'll progress more. Elite athletes from all sports

are living proof of this.

• You must "train" your body to be able to handle

more work by gradually increasing training volume over time (if you

decide to go for the higher volume approach). Do not make

huge jumps in volume or frequency.

T-Nation: Okay, we're also told by many experts never to train

to failure, but again, most top bodybuilders train to failure. Is

this a testament to their great genetics and drug use, or are we

normal folks missing something here by avoiding failure

training?

Thibaudeau: I'll take the easy way out with this one!

I'm working on a new book that will be called High-Threshold Muscle Building and there's a section on

training to failure. I'm gonna draw from it to give the

readers a more complete answer... and to get the word out about

the book!

From the upcoming High-Threshold Muscle

Building:

Few concepts in the world of strength training have been more

hotly debated than the need (or not) to reach muscle failure during

your sets. Is it necessary for muscle growth? No, however I feel

that it's necessary for optimal growth.

Some argue that training to failure is either dangerous or can

lead to CNS fatigue. Others argue that training to failure too

often will cause an excessive amount of muscle damage and can lead

to localized overtraining. I think that some of these

misconceptions stem from the fact that muscle failure isn't well

understood.

The biggest proponents of training to failure have defined it as "creating a maximum amount of inroads to the muscle on each

set." This is fine and well. However, am I the only one who

doesn't understand what they mean by that? So I feel that it's

important to correctly describe what muscle failure is and why it

happens. This information will allow us to make an objective

assessment of the need (or not) of training to failure.

What is the Point of Failure?

Failure is actually not complicated to understand. It's

simply the incapacity to maintain the required amount of force

output for a specific task (Edwards 1981, Davis 1996). In other

words, at some point during your set, completing repetitions will

become more and more arduous until you're finally unable to produce

the required amount of force to complete a repetition. This is

muscle failure. Failure isn't the amount of "inroad" to the muscle; it's nothing esoteric as we just saw.

|

The Causes of Failure

If the concept of training to failure is actually quite easy to

grasp, the causes underlying this occurrence are a bit more

complex. There's no exclusive cause of training failure,

rather there are quite a few of them.

1. Central/Neuromuscular Factors: The nervous system is the

boss! It's the CNS that recruits the motor-units involved in

the movement, sets their firing rate, and ensures proper intra and

intermuscular coordination.

Central fatigue can contribute to muscle failure, especially the

depletion of the neurotransmitters dopamine and acetylcholine. A

decrease in acetylcholine levels is associated with a decrease in

the efficiency of the neuromuscular transmission. In other words,

when acetylcholine levels are low, it's harder for your CNS to

recruit motor-units and thus you're unable to produce a high level

of force output.

2. Psychological Factors: The perception of exhaustion or

exercise discomfort can lead to the premature ending of a set. This

is especially true of beginners who aren't accustomed to the pain

of training intensely.

Subconsciously (or not), the individual will decrease his force

production as the set becomes uncomfortable. This is obviously not

an "acceptable" cause of failure in the intermediate or

advanced trainees, but beginners who are not used to intense

training could slowly break into it by gradually increasing their

pain tolerance.

3. Metabolic and Mechanical Factors: It's well known that an

increase in blood acidity reduces the magnitude of the neural drive

as well as the whole neuromuscular process. Lactic acid and lactate

are sometimes thought to be the cause of this acidification of the

blood, but this is actually not the case. The real culprit is

hydrogen.

Hydrogen ions can increase blood acidity, inhibits the PFK

enzyme (reducing the capacity to produce energy from glucose),

interferes with the formation of the actin-myosin cross bridges

(necessary for muscle contraction to occur), and decrease the

sensitivity of the troponin to calcium ions.

Potassium ions can also play a role in muscle fatigue during a

set. Sejersted (2000) has demonstrated that intense physical

activity markedly increases extra-cellular levels of potassium

ions. Potassium accumulation outside the muscle cell leads to a

dramatic loss of force which obviously makes muscle action more

difficult.

Finally we can include phosphate molecules into the equation.

Phosphate is a by-product of the breakdown of ATP to produce

energy. An accumulation of phosphate decreases the sensitivity of

the sarcoplasmic reticulum to calcium ions. Without going into too

much detail, this desensitization reduces the capacity to produce a

decent muscle contraction.

4. Energetic Factors: Muscle contraction requires energy.

Strength training relies first and foremost on the use of

glucose/glycogen for fuel with the phosphagen system (ATP-CP) also

playing a role.

Intramuscular glycogen levels (glucose reserve in the muscle) is

very limited and can become depleted as the training session

progresses. The body can compensate by mobilizing glucose stored

elsewhere in the body (but this amount is also finite), by

transforming amino acids into glucose (which is a less powerful way

of producing energy for intense muscle contractions) or turn to

free fatty acids and ketone bodies.

The last two solutions can't provide energy as fast as

intramuscular glycogen can. As a result, even though it will be

possible to continue exercising with a depleted muscle, it's

impossible to maintain the same level of intensity and force

production.

So as you can see, it's impossible to attribute muscle failure

to a single phenomenon. Rather, it's a mix of several factors

that cause muscle failure. Contrary to popular beliefs, reaching

muscle failure in one set doesn't ensure the complete fatigue

and stimulation of all the muscle fibers in a muscle. Far from it!

Failure can occur way before full contractile fatigue has been

reached. This means that the "one set per exercise to

failure" method isn't ideal for maximal growth. As a part of a

more complex training plan it can be beneficial from time to time,

but not as a discrete training system.

|

At some point it becomes necessary to increase training volume

to fully stimulate a larger pool of muscle fibers. Remember that

simply recruiting a motor-unit doesn't mean that it's

been stimulated. To be stimulated a muscle fiber must be recruited andfatigued (Zatsiorsky 1996).

If training to failure doesn't ensure full motor-unit

stimulation within a muscle, not taking a set to positive muscle

failure (the point where a technically correct full repetition

can't be completed) is even less effective since it won't fatigue

the HTMUs as much. And remember that a muscle fiber that isn't

fatigued isn't fully stimulated! In other words, training to

failure doesn't guarantee maximal motor-unit stimulation, but

not taking a set to failure drastically reduces the efficacy of a

set.

This indicates that high volume of work without going to failure

isn't ideal for maximal muscle growth (but it's okay for

strength and power oriented training). But at the other end of the

spectrum, low-volume training taken to failure isn't ideal

either. Failure and volume are both needed for maximal motor-unit

stimulation. That's not to say that you should use a huge

volume of work, but a moderate volume of sets taken to failure is

necessary for maximal muscle growth.

And what about the so-called CNS drain that can occur when you

take your sets to failure? I do agree that for continuous

improvements to occur one should avoid CNS burnout/overtraining

(also called the Central Fatigue Syndrome). And I understand the

theory behind avoiding going to failure: going to failure increases

the implication of the nervous system because as fatigue sets in

(accumulation of metabolites and energetic depletion) it must work

harder to recruit the last HTMUs.

The argument is that we should minimize training that has a high

demand on the nervous system. However, most people who espouse the "don't go to failure" theory are generally

proponents of heavy lifting and/or explosive lifting, both of which

are just as demanding (if not more) on the nervous system as

training to failure. Why are they against one neural intensive

method but for another one?

The fact is that the CNS is an adaptive system just like the

rest of our body and it can become more efficient at stimulating

muscle contraction when it's trained properly. And while CFS

is a real problem, its occurrence in bodybuilders or individuals

training for muscle mass gains is minimal, close to nil in fact.

Sure, we can suffer from CNS fatigue after a training session

(just like our muscles are fatigued too), but the body can recover

from that. Neurotransmitter depletion might be a concern, but

rarely is a real problem. Using a supplement like Biotest's

Power Drive

can help in that regard by boosting acetylcholine and dopamine

levels.

Key Points

1. Muscle failure isn't an indication that every muscle

fiber within a muscle has been fully stimulated. However, going to

failure will make sure that you're getting the most out of that

set.

2. Muscle failure can occur because of neural, psychological,

metabolic, or energetic factors.

3. A moderate amount of work to failure is required for full

motor-unit stimulation within a muscle.

T-Nation: Good stuff, Christian, lots to think about. Thanks for

the interview!