Every successful career has hiccups along the way. Making mistakes and learning from them are the bricks and mortar of a long and productive career.

I'll be the first to admit that I've stolen points from the best of 'em to advance my own training knowledge. In doing so, there were principles and exercises that I readily accepted as gospel and would defend from the tallest tree.

This is how it is. Disagree? Well, you're just misinformed.

But times change. New research is performed, new information becomes available, and it only makes sense that methodologies would evolve. That is, unless you'd rather stay "right" than admit you were wrong.

My one-track mind nearly eliminated the possibility of using conventional "cardio" for fat loss. I sided with the many coaches who argued that slow-go cardio was a potential muscle-waster, not to mention woefully inefficient at burning calories.

Though there is some science to support this position, I realize now that there's a big fat exception to this: whether to perform steady state cardio depends on the size and musculature of the individual.

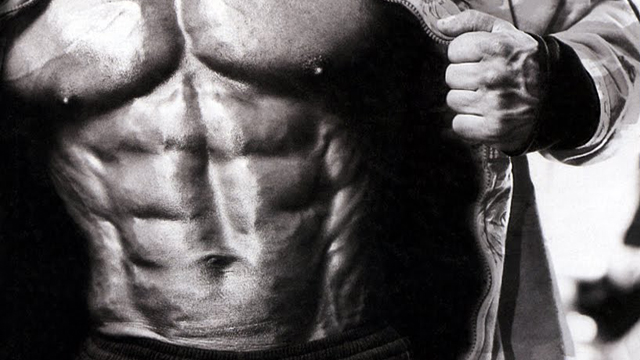

Steady state cardio – especially the fasted version – can be a great tool for intermediate and advanced trainees that carry a significant amount of muscle mass.

People generally support interval training as it will have a greater affect on the metabolism, primarily because it promotes two things:

- Oxygen debt

- Utilization of fast-twitch muscle fibers

But if you're carrying a lot of muscle, chances are you've lifted, pushed, and pulled a lot of heavy things to get there. That means your fast twitch fibers have been thoroughly exercised – since they're the strongest fibers available – so it won't be the end of the world if you add in a bit of steady state cardio during fat loss phases.

Bodybuilders are perfect examples. While some high-intensity cardio has made it's way into their fat loss programs, isolation splits combined with a good, clean diet, and fasted and/or post workout cardio still dominate the scene. This improves thermogenesis – heat production within the body – that helps burn fat.

While anaerobic training is what makes athletes like sprinters and running backs get so lean and muscular, most of us are just regular exercise enthusiasts, not pro athletes, meaning we can't expect to train – or look – like Adrian Peterson.

But we can lift weights and train our strength and anaerobic capacity. Once we're big and strong, as long as we don't go overboard, we can use steady state cardio to achieve some solid fat loss.

Don't worry, I'm not about to completely outlaw such a great exercise. But here's what I've found.

I've had several clients complain of knee discomfort during or after a workout that involved a variation of the glute-ham raise (GHR), most often the eccentric GHR.

At first, I didn't think that this exercise was the culprit, but a couple of sit-downs with a practitioner-buddy of mine had me thinking it might be something to use on a case-by-case basis.

Some say the GHR is a "closed chain" movement since the feet don't move anywhere during the movement, but here's the catch. Just like a seated leg extension, a GHR makes only one set of muscles act on the knee joint during the movement (hamstrings). There isn't a co-contraction of muscles on both sides of the joint.

This can produce the same amount of shear from the opposing side, and therefore pull on the corresponding ligaments that attach to the tibia away from the femur.

With an actual GHR machine, it's normally not that bad. But when we go into variations like the makeshift eccentric GHR, the shear is intensified since the entire weight of the body is resting on the tibia, in addition to the hamstrings' contraction pulling it even further. That means a lot of stress on your PCL.

Still, some are more resilient to shearing forces than others. We all know guys who've been doing leg extensions and other open-chain movements for years with zero joint problems, while others get shooting pains if they so much as look at a leg extension machine.

The moral of the story? If you're using the eccentric GHR in your training, be cautious of its effects. Hopefully you don't fall into the contraindicated group.

The more I looked into it, the more variety I found in trainers' definition of the term "functional."

Sure, we have the basic exercises that have carryover into typical day-to-day situations like squatting, deadlifting, and standing pressing. But do we avoid biceps curls, hamstring curls, or bench presses because they seemingly don't carry over to our daily grind?

Fact is, functional training can take on whatever description we want it to. A hamstring curl action has very little "real life" application, but one of the functions of the hamstrings is to flex the knee, and hamstring curls recreate this movement.

I advocate the big bang movements as much as the next guy. If our muscles aren't performing their prime actions the way they should, then the number one exercise choices should always be those that enhance those prime actions.

However, I'll humbly add that most T Nation readers seek strength and hypertrophy. What if we want bigger arms, and we've already spent the last three months overhead pulling, farmers' walking, and close-grip pressing our way to oblivion?

Do we continue to avoid biceps curls because they're "isolation" movements despite the stimulation for the biceps they provide? Do we still steadfastly avoid skull crushers or pressdowns, even though our horseshoes better resemble shoelaces?

Focus on the must-do's first, keeping your muscular and skeletal health in check, but sometimes building up your body means training like a bodybuilder. In certain cases, that means isolating right down to the muscle.

For a long time I used this stuff as an "answer." Today I use it as a "prescription." In almost all cases, muscles become tight because of a deficient muscle somewhere else. Usually the tight muscle is taking on the role of a muscle that isn't pulling its own weight. A perfect example would be a pair of tight hamstrings picking up the slack for a set of inactive glutes.

A good rule of thumb is that when a muscle appears deficient, the answer isn't always to give that muscle more attention. Considering this, we should be able to look at our weak links to see which smaller muscles aren't doing everything they should to contribute to a functional body.

Flexibility and ROM increases will come immediately through restoring your antagonistic balance. This can be as simple as activating dormant muscles that for a while have been compensated for by the big dogs.

The true "answer," in my book, is mobility. One of my favorite books is Assess and Correct by Eric Cressey. It has hundreds of drills that make small muscles fire up to create or restore range of motion.

I'm not saying that stretching and foam rolling to respectively lengthen and improve tissue quality is a waste of time. I still use them, and you should, too.

My advice is to turn it into a tactical approach. Instead of prescribing stretching and rolling to any ailment under the sun, start thinking in three ways: improve tissue quality first, activate muscles second, reduce inhibitions third.

Use foam rolling for myofascial release, dynamic warm ups to add range of motion and activate dormant muscles, and then static stretching to muscles that are "blocking" proper movement patterns, such as tight hip flexors affecting pelvic position during a back squat or Romanian deadlift.

This might be stating the obvious, but not all programs are for everyone.

Training volume should be tailored to each athlete, and failing to recognize this is what keeps some athletes from seeing continued progress.

I first experienced this as a collegiate track and field athlete. We sprint athletes would have our workouts set by the coach, though we'd train alongside the athletes from other disciplines (the jump athletes, etc). This was done for simple time management reasons, as it was the easiest way to train a bunch of athletes at the same time.

But each athlete isn't going to respond to the same training volume the same way – especially when our "base" workouts, usually Mondays, would often look something like this:

- Dynamic warm-ups/flexibility work

- Drills

- Plyometric/ballistic training – Static jumps, stairs, uphill jumps, med ball work

- Base training workout – 300m + (2)200m + (2)150m @ 85% of max effort

- Core training circuit or weight training circuit

Needless to say, that's a tough workout and would leave me destroyed. I'd be so sore that it would sometimes affect the practice on Tuesday.

This example is intended to show that quality is everything where training for performance is concerned. Big, tough, and heavy workouts have their place, but if you want to get stronger, bigger, or both, you have to know when your body is working at its physiological peak, and when it's starting to go down hill.

Once that line is crossed, it's a good idea to cut your workout short, or heavily modify its contents.

I'm sure my track coach had the best of intentions, but not everyone's going to have the same threshold and work capacity. Some levels of DOMS don't need to be reached, and certainly not repeatedly.

Since you're not training with a team and can control your workout, don't be afraid to modify your programming. It may not take longwinded workouts to make your muscles big and strong.

The smarter I get as a trainer, the more I'm reminded that there are many methodologies, techniques, and strategies for doing things, and many ways to achieve a desired result.

However, true wisdom comes from recognizing that what might work supremely well for person A could be a disaster for person B. In reality, it's not the exercises that are contraindicated, but the people who do them. Stay aware of that and play your game, not someone else's.

With age comes perspective and more importantly, wisdom. A lot might change in the next five years, but I can't see that principle going anywhere.