The squat is one of the blessed few exercises that everyone, regardless of training orientation, seems to agree is a great training option.

Strength enthusiasts squat to improve force production, bodybuilders squat to build massive legs, the functional folks squat to improve performance of everyday activities, and the physical therapists use the squat as an assessment and rehabilitation exercise.

In this article, I'll share the top 7 squat tips that have helped our team at Performance U get better results with all our clients, from Pros to Joes.

1. Finding the Best Squat Stance for You.

Coaches like to argue for or against different squat stances. While a good strength training argument is always fun (in small doses), what's really important is finding the squat stance(s) that work best for you.

In other words, don't believe in a one-size-fits all approach to squatting, or any other exercise for that matter.

Here's a quick and easy squat assessment from hip rehab expert Phil Malloy, which we use to help find clients' safest and most comfortable foot position based on their specific hip structure and function.

To expand a bit on what Dr. Malloy briefly mentioned in the video about "over-coverage" and "under-coverage" in the hips:

- People with a hip external rotation limitation may do better with a more parallel stance, or in certain cases, a slightly internally rotated squat stance.

- Note: If someone can only squat with internally rotated hips, we'd use a different exercise option because we're not comfortable squatting high-loads in that position.

- People with hip internal rotation limitations may do best squatting with a more externally rotated foot position and a wider stance.

- Someone with zero hip limitations has the option of mixing up their stances for training variety.

Also, keep in mind that Dr. Malloy doesn't try to fix, rehab, adjust or correct the squat movement pattern in any of his patients without first getting an X-ray to find out what's going on inside.

This makes sense because if you move in a way that goes beyond (or against) your body's structure, you're likely to get hurt – another reason to not get too preoccupied with a specific (predetermined) type of squat movement pattern.

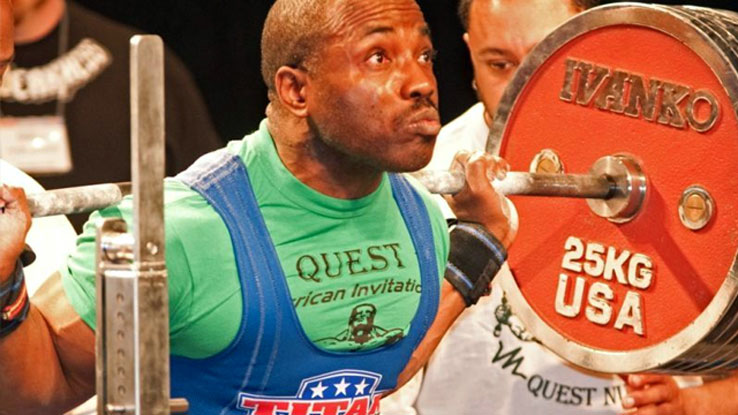

2. High-Bar Versus Low-Bar Placement

As you can see in the image to the left, bar placement can affect the force angles and postures involved in the barbell back squat.

When individualizing programs, bar position depends on the ability and goals of the specific client or athlete we're working with.

We use the high-bar squat position...

- When trying to emphasize quadriceps size and strength, since the body position can remain more upright.

- If there's limited shoulder external rotation or thoracic-spine extension. Alternatively, we'll use a front squat.

- When working with bodybuilders using lower loads and higher reps for more time under tension.

- When trying to be a bit more low-back friendly, as the more upright torso reduces potential shear forces on the spine.

We use the low-bar squat position...

- When trying to emphasize the hips and low-back, since the body stays more forward.

- When going for near-max loads using lower rep ranges, as a lower-bar position helps bring more of the powerful hips into the game. It also shortens the lever arm on the low back, allowing the hips to work from a better mechanical advantage.

- With females, since girls tend to already be more quad dominant. We focus their lower-body training towards balancing their quad strength with extra hip and hamstring work.

- If someone lacks ankle mobility, we'll use a lower-bar position since it better accommodates a more hip-oriented squat action.

- For those with great shoulder mobility and T-spine mobility, we'll incorporate the low-bar position.

"Back-Friendly" Bar Positioning

In our experience, both back squat bar placement methods can be considered "back-friendly," it just depends on the situation.

- If you have restricted ankle mobility – like most average gym goers do – we recommend a lower bar position because restricted ankle dorsiflexion will cause the torso to tilt forward, which places more stress on the lower back the higher the bar is placed.

- On the other hand, if you have "back issues," we go for a higher bar position – provided your ankle mobility is fine – to keep the torso more upright and place more stress on the legs and less on the back.

However, when working with someone with no limitations, we may alternate bar placement with each consecutive squat workout to create training variety and change the force vectors involved within the same movement pattern.

3. Add Calf Raises

We've found when working with bodybuilders, figure athletes, and performance athletes, adding in a calf raise after every squat rep is a small tweak that can make a big change to the intensity of their squat workouts through more lower-body muscle involvement.

This simple tweak can also increase the eccentric aspect of the squat, provided the athlete is able to lower in one smooth motion as in the video below.

A few more coaching tips:

- Squats work great "as is," which is why we don't always add in the extra calf raise. But we do like to sprinkle in a few sets here and there to spice up squat workouts.

- We've found that using sets of 8+ reps works best when incorporating the calf raise, since the loading potential is somewhat limited by what your calf musculature can lift.

- When using the calf raise at the end of each squat, we coach our athletes to explode up (out of the bottom) as if they're going to jump. We've found giving our athletes a movement oriented task helps with timing and rhythm as opposed to "squat first, then raise your heels."

4. 1-1/2 Reps

As covered in my article Midrange Partials for the Best Pump of Your Life, basic physiology tells us that, "Muscles have the lowest potential to generate force when they're either fully elongated (stretched) or fully shortened (contracted).

They generate the highest possible force in the middle – halfway through the range of motion. The more force you generate in this midrange, the more motor units you recruit."

The 1-1/2 rep system takes advantage of this by using mid-range partial reps in conjunction with full range reps.

Here's how we use 1-1/2 rep squats:

- Squat all the way down, but only come back up half way. Then go back down again and come up all the way to the start position. That's one rep.

- We usually do sets of 5-8 reps, which is a lot of work when you factor in all the half-reps that don't allow you to rest at the top, which provides more overload by increasing time-under-tension.

5. Contrast Training

We use two primary methods to help our clients get stronger and improve performance. One is physiological (hardware) based, which means putting on muscle size (hypertrophy). The other is through neural (software) based training. Contrast training gives us both methods in one comprehensive training method.

As I covered in this article, contrast training involves starting with a heavy lift and immediately following it with an unloaded explosive exercise using the same (or similar) movement pattern.

Here's our favorite way to use contrast training for squats:

For physique athletes. We use contrast training to increase intensity and add training variety. Perform 3-4 sets of 6-10 reps of the strength exercise followed by another 6-8 reps of the equivalent explosive exercise.

For performance athletes. Since our focus with this population is less on volume and more on intensity (i.e. force production) perform 4-6 sets of 3-5 reps of the strength exercise followed by another 3-5 reps of the equivalent explosive exercise.

6. 7/4/7 Squats

I learned the basic 7/4/7-workout protocol from coach Robert Taylor, the owner of Smarter Team Training, who uses it with the elite athletes he trains. He learned it from longtime NFL strength coach Mark Asanovich who was head strength and conditioning coach for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

Although this may be new to you, rest assured it's been battle-tested and proven effective with some great athletes.

Here's coach Rob Taylor discussing the basic 7/4/7 system and demonstrating how you can use it with virtually any strength exercise:

Pure 7/4/7 Squats

Start with 7 reps using a moderate weight load. Without resting, increase the load and bang out 4 reps. Finish the set by doing another 7 reps using a lighter weight load.

The Performance U – Hybrid 7/4/7 Squat Protocols

When looking to add some volume to our squat workouts, we often use two hybrid 7/4/7 squat protocols, which we developed to take the original 7/4/7 idea a step further.

Hybrid Squat Protocol 1

7/4/7 – Front Squat/Squat Jump/Back Squat + Calf Raise

Perform 7 front squats, then 4 squat jumps (as high as you can go), then 7 back squats + calf raise, all using the same weight.

This is a great squat protocol for increasing power-endurance in the lower-body.

Hybrid Squat Protocol 2

7/4/7 – Front Squat/Back Squat/Jump Squat

We'll also mix up the order a bit by performing:

7 x Front squats

4 x Back squats (using a heavier weight than you did with front squats)

7 x Squat jumps (as high as you can go)

For performance athletes. We use 7/4/7 squats to add volume and create a major pump (i.e. cellular swelling), which can help spark new hypertrophy.

For performance athletes. We use 7/4/7 squats to help increase stamina by building power-endurance.

7. Gender Differences

Here's some interesting research done by Dr. Mark McKean on the gender differences between how men and women move when squatting.

Dr. Mark McKean runs the strength & conditioning research program at the University Sunshine Coast in Australia. He's also coached athletes to international level competition in 18 sports and helped some win both Olympic and World Championship medals in five sports.

- Men and women require different squatting strategies as the timing of when each joint and segment reaches maximum is different in all squat variations.

- Knee angle differs the most between males and females and this appears to be influenced by different segment lengths of the lower limbs.

- When squatting, tall women tend to alter knee angles and tall men tend to alter hip angles.

- To adjust body position, men tend to alter trunk angle while women tend to alter pelvis position.

- Men appear to be inherently 'stiffer' in the lumbar spine than women, suggesting that women who squat will benefit from a good core strengthening program.

- Women tend to achieve better coordination in all squat variations of load and stance, but men tend to achieve a better level of coordination only when squatting with heavier loads.

It's as if the load tends to optimize their patterns by either allowing the muscles and fascia to be stretched by the load, or with stronger, stiffer muscles the extra load provides equal tension and improves coordination.

This doesn't mean that when a male squats poorly the answer is to go and load up his squat weight; just be aware that the difference between unloaded and loaded squats will look more different in males than in females.

When teaching men and women to squat I still go with the overall strategy of good squatting practice, but I'm also aware that the genders will correct and adjust position differently. The big indicator for gender differences is the knee angles and subsequent trunk position. If you keep an eye on this you'll see what I mean.

Final thoughts

I've covered a bit of everything on squats, from movement assessments, to new rep schemes, to exercise variations, to gender differences.

I want to leave you with one more recommendation, from Dr. McKean on common mistakes coaches make when coaching the squat:

"Coach for an improved pattern rather than a predetermined pattern or a one-size-fits-all approach. There's no best way to squat if you refer to specifics such as joint angles, or feet position, etc., but I do believe there are 'ideal' strategies to teach.

"Try to avoid over teaching or over cuing. This really comes about from the way most professionals are taught, as during this process they're told how to squat rather than how to 'teach' people to squat."

Questions or comments? Post them in the LiveSpill!