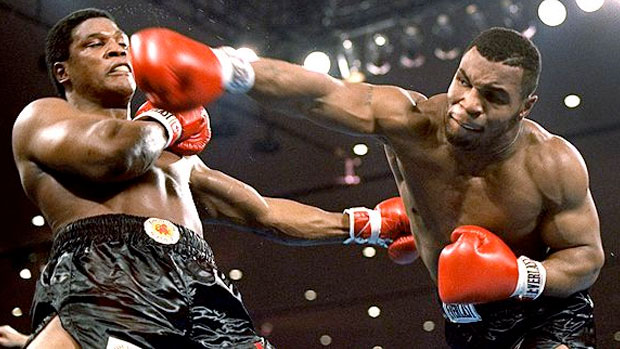

"Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the face." — Mike Tyson

Picture a large plastic zip tie, about an inch wide. The smaller

versions are sometimes used to tie garbage bags; soldiers and

police officers use the large ones to restrain people. Anyone could

figure out how to thread a zip tie: You put the little end through

the hole and pull on it.

In 2001, psychologists from Yale and the U.S. Army imposed this

task as part of a scenario conducted in a study with a group of

Army Special Forces soldiers. During the scenario, the soldiers who

had not pre-threaded their flex cuffs in advance found themselves

almost incapable of using them.

What went wrong? Surely this wasn't an inept group of men.

They're some of the toughest, most highly trained in the world; the

reason for their failure couldn't possibly be inability.

Something beyond physical skills comes into play.

Come Out Fighting

If you're a mixed martial artist, you'll know how to do an

armbar and a triangle choke. If you're a football player, you know

that you can catch a football or tackle an opponent who dares to do

such a thing in your area of the field. If you're a climber, you

know how to pull gear off your harness with one hand, place it, and

clip your rope into it.

You've done these things thousands of times, and know how to do

them well.

Yet numerous people have found themselves suddenly incapable of

doing something as simple as dialing 911. They forget the tiniest

details, like the need to dial 9 for an outside line, or they

inexplicably call 411 over and over.

In my first MMA fight in San Diego, I found myself repeatedly

locking my opponent into a guillotine choke, yet I was unable to

finish the choke and submit him. I lost the fight by a single point

after going into overtime.

Only afterwards did I realize that I'd been keeping my

opponent's arm inside the choke and leaving one side of his neck

open. It was a mistake that I'd probably made countless times in

training, but had always had the presence of mind to correct.

I could lock this choke out smoothly in a training environment,

so why couldn't I think well enough to do the same thing during the

fight, in front of thousands of people? Why couldn't the Special

Forces guys figure out how to thread their flex cuffs? How could a

person possibly forget how to dial 911?

Performance Degradation

The scenario being conducted by the Special Forces soldiers was

a close-quarters combat (CQC) simulation. It involved urban warfare

with their real weapons loaded with paint bullets, hand-to-hand

combat with role players wearing impact-reduction suits, an

overwhelming noise stimulus, and poor, macabre lighting.

At random intervals throughout the scenario, the SF operators

would, without warning, receive a significant pain stimulus to the

upper body via an electric shock in order to simulate a gunshot

wound.

Under this level of stress, the warriors were incapable of

performing unrehearsed complex motor skills, such as threading

their zip cuffs to subdue their adversaries.

The same performance degradation occurs with the person trying

to dial 911, the climber who bumbles repeatedly while hanging from

his fingertips at the crux of a dangerous route, and a fighter who

suddenly realizes that what he knows in the gym is not what he

knows in the ring.

The skills you possess in a calm, controlled environment will

probably not be the skills you possess when it really matters. The

impact of stress may mean the difference between victory and

defeat, a clean climb and a jarring fall, or even life and death.

The good news is that the effects of stress can, to some extent,

be controlled.

Your Body Under Stress

"Fear makes men forget, and skill that cannot fight is

useless." — Brasidas of Sparta

The sympathetic nervous system mobilizes the body's energy

reserves during times of stress. It neutralizes processes

controlled by the parasympathetic nervous system, such as

digestion, while ramping up secretion of adrenaline and

noradrenaline, dilating bronchial tubes in the lungs, tensing

muscles, and dilating heart vessels.

It also causes your heart rate to increase.

There's a direct relation between stress-induced heart rate and

both mental and physical performance. Too low, such as when you're

just waking up, and you can't think or react very quickly. Too

high, and one's ability to think and perform motor skills degrades.

Dave Grossman, a psychology professor at the U.S. Military

Academy at West Point, former Army Ranger, and author of the book On Killing, uses a color-coded graph to categorize the

effects of heart rate on performance.

| Heart Rate (BPM) | Condition | Effects |

| 60-80 | White/Yellow | Normal resting heart rate |

| >115 | Fine motor skill deteriorates | |

| 115-145 | Red | Optimal performance level for complex motor skills and visual and cognitive reaction time |

| >145 | Complex motor skills deteriorate | |

| 145-175 | Gray | Black-level performance degradation may begin |

| >175 | Black | Cognitive processing deteriorates Blood vessels constrict Loss of peripheral vision Loss of depth perception Loss of near vision Auditory exclusion |

Grossman calls the earliest stages of this spectrum Condition

White. The boundary between here and the next stage, Condition

Yellow, is more psychological than physiological.

We first see major physiological changes around 115 beats per

minute. Between here and roughly 145 bpm is Condition Red, which is

the range in which the body's complex motor skills and reaction

times are at their peak.

Next is Condition Gray, which is where major performance

degradations begin to show.

Above 175 bpm is Condition Black, which is marked by extreme

loss of cognitive and complex motor performance, freezing, fight or

flight behavior, and even loss of bowel and bladder control. Here,

gross motor skills such as running and charging are at their

highest.

Remember, these effects are the product of psychologically induced stress, not physical stress.

An increased heart rate doesn't necessarily mean that you're under

psychological stress — you can run a few sets of wind sprints

and get your heart rate around 200 beats per minute without

forgetting how to use your cell phone.

These lines, however, aren't drawn with permanent marker.

It's possible to push the envelope of complex motor-skill

performance under stress right up to the edge of Condition Black.

It's also possible to reach Condition Black for its gross

motor-skill performance benefits, such as sprinting or deadlifting,

and then quickly recede to a calmer state to allow nervous system

recovery.

This generally occurs with specific, well-rehearsed skills. For

example, studies done on top Formula One drivers found that their

heart rates averaged 175 bpm for hours on end. These drivers

perform a limited set of finely tuned skills with extraordinary

speed, under a good deal of stress.

Likewise, the top performers in the Special Forces study had

maximum heart rates of 175, while those who were slightly less

proficient typically had max heart rates of 180 bpm. In both cases,

175 is the maximal rate before high-level performance drops off.

At a certain point, an increased heart rate becomes

counterproductive because the heart can no longer take in a full

load of blood, resulting in less oxygen delivered to the brain.

That, in theory, could be the cause of the performance decrease

seen above 175 bpm.

Stress Inoculation

"No man fears to do that which he knows he does well."

— Duke of Wellington

As defined by Dave Grossman in another of his books, On

Combat, stress inoculation is a process by which prior success

under stressful conditions acclimatizes you to similar situations

and promotes future success.

In a classic stress inoculation study, rats were divided into

three groups. The first group was taken directly from their cages,

dropped into a tub of water, and observed with a timer. It took 60

hours for all of them to drown.

The second group was taken out of their cages and held upside

down to create stress. After the rats gave up on kicking and

squirming and their nervous systems went into parasympathetic

backlash, they were placed in the tub of water. This group lasted

20 minutes before drowning.

The last group was given the same upside-down stress treatment,

and then placed back into their cages to recuperate. This was

repeated several times until the rats became accustomed to the

stressor. Finally, the rats were taken out, given the stress

treatment and placed immediately in the water. They swam. For 60

hours.

The repeated bouts of stress allowed the rats to become

inoculated against the stressor. Even with an event that had cut

the lifespan of the previous group down to 20 minutes, the third

group was able to perform at the same level as the group that faced

no stress at all.

Immunizing Your System

There are many forms of stress inoculation, and to be most

effective, they must be precisely geared toward one's chosen

activity. Fighters inoculate themselves by simulating a fight

through sparring. Firefighters are inoculated against fire by being

exposed to it repeatedly. Skydivers eventually develop a high level

of familiarity and comfort with great heights.

As a member of a U.S. military Special Operations force, I know

that we wanted our training to be as realistic as possible.

Military training has improved steadily since WWI, moving toward

increasingly realistic targets. The closer the training scenario

resembles the real thing, the greater the performance carryover

will be.

This is called simulator fidelity: Switching from simple

bull's-eye targets to silhouettes and then to 3D pop-ups was

one such evolution, but we would take this a step further.

The first time I jammed a magazine loaded with blue paint

bullets into my assault rifle, dove out of an ambushed car, and

fired them at a living person while sprinting for cover, it scared

the hell out of me. I had such tunnel vision that I could barely

see the person I was shooting at, let alone aim. After several

repetitions, however, I was able to stabilize myself, turn toward

the oncoming fire, and hit my target.

Despite the necessary specificity, there's still a general

carryover. Adapting yourself to a stressful situation seems to

create a sort of "stress immune system," which allows greater

tolerance and more rapid adaptation to other stressful situations.

In On Combat, Grossman cites an example of a full-contact

fighter who joined his team for CQC weapons training in a kill

house. During the first engagement, the fighter's heart rate shot

to 200 bpm, and he dropped his weapon. However, his background in

facing other stressful situations allowed him to adapt relatively

quickly. By the end of the day, he was performing superbly.

Learning a Motor Skill

The field of neuroscience has a variety of theories on how

learning occurs and exactly how the brain functions to create a

conscious, intelligent human.

Jeff Hawkins, author of On Intelligence and inventor of

the Palm Pilot, has developed a theory that the brain is not a

computer (a commonly attempted analogy), but in fact a system that

stores experiences in a way that reflects the true structure of the

world.

The brain remembers sequences of events and their nested

relationships, and then makes predictions based on those memories.

These memories are stored in the neocortex, a

two-millimeter-thick sheath that coats your brain. Its 30 billion

nerve cells contain all your skills, knowledge, and life

experiences. (Fun fact: For all the similarities in brain structure

across the animal kingdom, mammals are the only ones with a

neocortex. Suck that, reptiles!)

Now let's talk about how you learn and remember motor patterns,

so you can understand what's happening when someone throws a ball

at your head and you grab it without having to perform physics

calculations to figure out that it's on a collision course with

your teeth.

The neocortex is divided into six layers that function in a

hierarchy. Each layer attempts to store and recall sequences, with

higher layers having the ability to put together more comprehensive

sequences or concepts than lower layers.

For instance, say you're grappling in a jiu jitsu match. You see

an opening, and "triangle choke" flashes through the upper level of

your neocortex. This command is passed down to the next layer,

which breaks the concept down into the further sequences: "Drag one

arm, throw leg over neck, shift hips."

At the next layer in your cortex, these commands are broken down

further: "Tighten fingers around opponent's wrist, and pull in such

a way as to prevent him from posturing up and

escaping."

Now let's say that your opponent pulls out of the triangle

choke. The predicted sequence being performed is supposed to end

with your opponent being choked and submitted, but it doesn't match

the reality. So the new sensory data is passed back up the

hierarchy until a suitable sequence is found and passed back down

again.

Too Much Information

If you've ever taught someone a movement in the weight room,

you've probably been frustrated by the process. Teaching someone a

kettlebell swing involves a number of cues which, for an

experienced lifter, are ingrained so well and so low in the cortex

that they can be carried out without conscious thought.

Not so with the newbie, whose upper neocortex is at full tilt

processing and associating commands like "keep your heels on the

ground," "neutral spine," and "fire your

glutes." This is often when you'll hear the trainee say things

like, "There's so much to remember at once."

Within the newbie cortex, the uppermost level is occupied just

trying to ingrain one of those completely foreign commands. This

doesn't leave room for much else, since the higher a pattern must

go to be recognized, the more regions of the cortex must become

involved. The sensory feedback in response to those actions is

completely novel, so the patterns from something as simple as

putting one's heels on the ground create countless new

associations.

After a while, the cortex will be able to associate a variety of

new sensations with expected forms of feedback. Now, when the

trainee hears the command, his cortex will be able to predict what

it will feel like to carry it out.

The command can now be relegated to a lower level of the

hierarchy, freeing the upper levels to process other commands. The

more associations brought on by repetitions of a movement, the

lower in the cortical hierarchy the pattern can be

relegated.

Think of the first time you ever rode a bicycle. It took all of

your conscious energy. But after countless repetitions under

varying conditions, you can do it while talking to your buddy about

the worlds dirtiest strip club (it's in Mexico, in case you're

wondering) — even if something unexpected comes up, like

grandma walking in front of your bicycle.

This is why repetitions are so crucial in learning a motor

skill. More repetitions equal more associations and a more strongly

ingrained motor pattern.

Quality Matters

We know that repetitions create auto-associative memories within

the cerebral cortex, which in turn dictate behavior. This process

happens for everything, from shooting a basketball to lifting a

barbell to throwing a punch.

Since you're ingraining a pattern with each repetition, it's

crucial that any sort of technique be drilled flawlessly. Even in a

controlled environment, with a punching bag for an opponent, poor

technique in training will be reproduced when it matters. You

can't train sloppy and then expect to perform

well.

Even if two different motor patterns are ingrained, the act of

deciding between the two and discarding the poor one will slow

reaction time and performance. A study conducted in 1952 by W.E.

Hicks found that increasing the range of potential responses from

one to two slowed down reaction time by 58%.

This is why running backs are taught to cover and protect the

football at all times, even when they're just practicing and

nobody's trying to strip it away. For the same reason, a shooter in

the military or law enforcement will never place his finger on the

trigger of his weapon until he's made the decision to fire.

When the trained motor pattern is relegated to subconscious

thought, there can be no question that it will be carried out

correctly.

Navigating a New World

So let's say you've been training, practicing, and grooving

the necessary motor patterns for your sport or profession. You're

ready, and you step into the ring, onto the field, or into the kill

house.

You've just entered a new world.

The patterns ingrained in your cortex will be largely

unassociated with this new, stressful environment, unless it's been

simulated using stress inoculation.

The higher stress levels and the overwhelming sensory feedback

from the ongoing situation are going to occupy the highest regions

of your cerebral cortex. Your only available motor patterns will be

those that have been relegated lower in the hierarchy. If you've

just learned a new skill, now would not be the time to

rely on it.

Complex motor control is going to diminish as your heart rate

increases; the exact heart rate at which this happens will depend

on your level of fitness and the degree to which you're inoculated

against stress.

As motor control drops off, the first patterns you'll lose are

those that haven't been strongly ingrained low in the hierarchy.

This applies to the ones with the most variations, the ones

you've rehearsed with the fewest repetitions, or those

you've learned in environments that least resemble this one.

During my first MMA fight, my immediately available motor

patterns were only the simplest: punch, kick, charge, clinch. Even

something as elementary as a guillotine choke took on sudden

complexity. In my adrenaline-fueled state of mind, I kept making

the same mistake as hard and fast as I could.

The same thing occurred with the Special Forces soldiers who

found themselves clumsily trying to jam a zip cuff together. The

pattern hadn't been rehearsed well enough to be recallable under

high stress, and was temporarily lost.

Those who wanted to dial 911 and found themselves listening to a

411 message over and over again were repeating the pattern of keys

most heavily ingrained. Their cortex knew they had to dial a

three-digit number and went with what it could immediately recall.

The 911 pattern hadn't been ingrained through physical

repetition. This is why it's actually a good idea to have your

family members practice this. (Just remember to disconnect the

phone first.)

The 16-Second Solution

There are three basic ways to combat the effects of stress on

physical performance:

• Stress inoculation

• Quality motor-skill repetition in an environment of high

simulator fidelity

• Biofeedback

I've already discussed the first two, which brings me to

biofeedback, the process of consciously regulating the body's

normally subconscious functions.

In On Combat, Grossman teaches a technique called

tactical breathing.

Next time you're under stress and feel your heart rate picking

up uncontrollably, take four full seconds to draw a deep breath.

Hold that breath for four seconds, and then exhale for the next

four seconds. Pause for another four seconds before repeating the

entire 16-second sequence at least three times.

This practice will immediately slow your heart rate and bring

your stress response under control. You'll feel mental clarity and

manual dexterity return, and it'll be easier to recall previously

ingrained motor skills.

Using Condition Black to Your Advantage

Gross motor skills like sprinting, charging, and picking up

really heavy stuff are at their peak in Condition Black, as

I've mentioned. That's why you see powerlifters slapping

each other, yelling, and generally making a ruckus before a big

lift. It's intentional nervous system arousal.

According to a study coauthored by Grossman, these performance

benefits peak within 10 seconds. That is, if you need to perform

your task within 10 seconds of reaching Condition Black, with your

heart rate exceeding 175 bpm, you'll get 100 percent of the

benefits. But after 30 seconds you get just 55%. It's down to

35% after 60 seconds, and 31% after 90 seconds. It takes a minimum

of three minutes of rest for the nervous system to fully recover

from this ordeal.

Prior to a big lift, you can maximize your gross motor skills by

artificially inducing stress and creating sympathetic nervous

system arousal. For the greatest benefit, you'll have to time it

well so that you take your position on the bar right around the

10-second mark.

Afterwards, in order to prevent subsequent drops in

nervous-system arousal, allow for at least three minutes of rest.

This is where tactical breathing can come in handy, as it can bring

your arousal levels back to normal and speed recovery.

Wrapping Up: Preparation Is Power

Sun Tzu wrote, "If you know the enemy and know yourself, you

need not fear the result of a hundred battles."

In this case, the enemy is stress, which, as you now know, comes

in a variety of flavors. You'll enjoy peak performance in

complex motor skills and reaction time at Condition Red, when your

heart rate is between 115 and 145 bpm. But even then, your fine

motor skills are starting to diminish, meaning that you might

struggle to tie your shoe even though you're at the top of

your game.

As your heart rate rises above 145 bpm, you might see a real

drop in your ability to do the things you can do perfectly well in

practice and other less stressful situations. And when you get past

175 bpm, you might not be able to do anything precisely the way

you've been trained to do it.

But even then, in Condition Black, you could hit a personal

record in the bench press or deadlift, as long as you start the

lift within 10 seconds of reaching that state of nervous-system

arousal.

And you can mitigate the negative effects of all these states of

stressful agitation by practicing your skills and your craft within

the parameters in which they'll be most difficult to perform.

That's why coaches whose teams are about to play in

notoriously hostile arenas will try to simulate that environment in

practice by bringing in noise machines or deliberately throwing

distractions at their players. And it's why elite military

units go as far as they can to simulate battle zones before the

soldiers are forced to perform their duties inside a real

one.

But, as Sun Tzu wrote, it's not enough to understand the

conditions in which you'll have to perform. You have to

understand how you react to those conditions. That takes more than

practice. It takes the right kind of practice.

The reward? When you perfect your game under properly simulated

conditions, you'll be invincible.